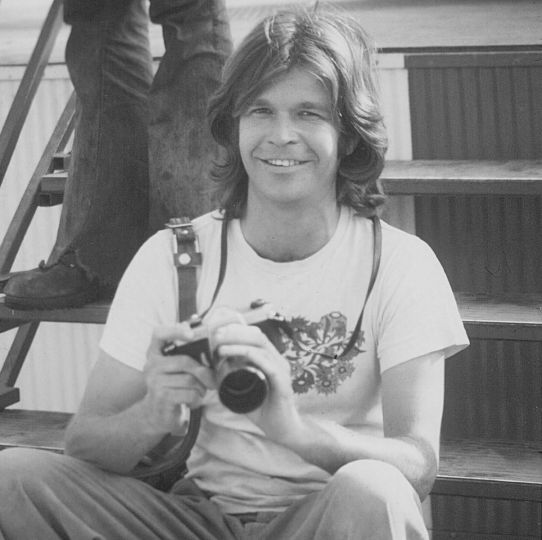

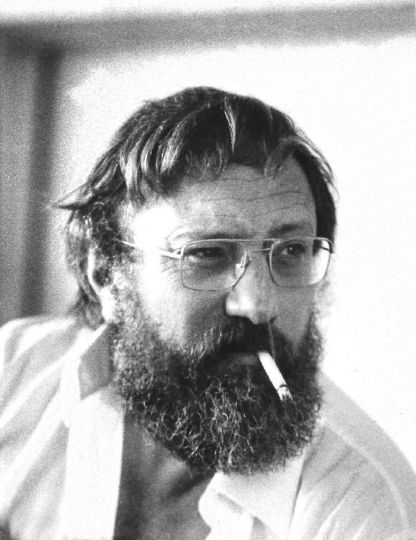

Her name was Jill Freedman. She was a great photographer and a difficult character. Which explains why her notoriety is far from being worthy of what it deserves. Four years ago, Jonas Cuenin painted this beautiful portrait of her. And browse her archives, she was one of the most talented photographers of her generation.

Jill Freedman charm is just so hard to resist. At seventy-five this lifelong lover of endless chats and priceless anecdotes has you spellbound one minute and laughing out loud the next. Not driven by any inner need, or because she’s showing off, but out of the same generosity that pervades her photography—an oeuvre harking back to a time when authorial compassion was the yardstick images were measured by. In her Harlem apartment, with Central Park a stone’s throw away, she brings the same warmth and tenderness to serving coffee as she does to the people in her pictures. Visitors are rare in this place that looks like a shrine—and with Jill Freedman looking like the keeper of the flame. There’s no obvious order: prints are jumbled with books and personal notebooks in an archive that makes you think of a treasure trove; and gives you an irresistible urge to rummage through a life that seems way out of the ordinary. A life Freedman enjoys recounting via numberless comedy routines and hilarious one-liners, against a constant musical background shot through with syncopation and jazz overtones. An unbroken theater that turns her images into fables and reveals her as much more than a virtuoso photographer. Big blue eyes, red cheeks, throaty voice, disheveled hair: she looks like a street clown, a force of nature—and every word brings the kind of transfiguration you find in remarkably gifted interpreters of life.

Freedman might love play-acting, but she also has her serious side: this is someone for whom there’s only a thin line between pleasure and pain. Milk-white winter outside, tropical living room inside: from her comfortable leather armchair she jams with words and stories, then without warning goes into a rock’n’roll rant against the rottenness of a world she will pillory until her dying day. Most of the time she’s striking back against the lunatic bombast of the women newsreaders on CNN and Fox News, delicious victims she turns on at noon with her latest toys: HD Ready screen, Apple TV, MacBook Air. Freedman is the “peace correspondent” she’s always wanted to be, permanently angered by American policy and, in this month of January, very moved by the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Each event, each tragedy, triggers the deep, intense look and the empathy for the underdog which, in this world of ours, can shock and sometimes disturb.

From the home that is her refuge, Freedman brings an acute eye to the 21st century. Makes you think of Chris Marker, the Red, holed up in his Paris apartment and studying the evolution of his fellow humans on TV. A strange kind of observation, this, passion mixed with laziness in powerful contrast with her intellectual vitality. “What saddens me is that at my age I have no certainties about human nature. I tend to like everybody, but with the firm conviction that any other animal species is more highly evolved than us. All we do is destroy. All we do with this high-speed information is use it to spy on each other. We’re the depraved monkeys you see in Hollywood movies. Ten years from now there might be no water or food left, and people don’t seem to care. Animals, as a rule, only kill to eat. That’s why I find politics so hard to put up with. History is repeating itself indefinitely. Did you see any bankers behind bars after the big crisis? Everyone’s so pleased with themselves for getting Obama elected. A president who’s a danger to the freedom of the press and in love with drones. You don’t get to where he is by being Mr Nice Guy. I can’t get all these stories and conflicts out of my mind. I think it comes from what happened in Paris. Those poor people. That really touches me. Make me stop… “

A rebel with a big heart, Freedman is also a marvelous storyteller. A bohemian with her own set of excesses, blind spots, and fears—the same as all the others, and even those who hid it, like Cartier-Bresson the drinker, Doisneau the insecure—together with the gut obsession they share: to work for the good of humanity. She insists that she’s still only twelve, and can see herself turning thirteen soon—but what for? “Twelve—not a bad age to already know everything about everything.” Her bohemia is total non-identification, being able to change her mind about everything, having fun with her friends, partying, having lots of lovers and physical affection—and traveling of course, literally and figuratively. She seems to have lived a thousand lives. Looking back to a happy childhood, she talks about her passion for softball—baseball’s kid brother, but played with a bigger ball. The only girl in her school team, the Mighty Midgets, she was shortstop, fielding between second and third base; as a batter she came in fourth, the “cleanup” position: “One day I hit two home runs in a row. I was the one who would drive you home.”

Later, at university in Pittsburgh, where she was born on 19 October 1939, she studied sociology and anthropology; interests she sometimes dropped for her other great enthusiasm, music, and the jazz group she sang with in bars full of workers and miners. Using the same warm, dense voice as on this fine winter afternoon, as a crackly LP murmurs the opening bars of her all-time favorite, Stan Getz’s Here’s That Rainy Day: “Da da da da Da deedeeda dadadee… Da da da Da Deedee… Da da Deedooda Dedoo Oodee… Oo sweet ooosh ee da da didoo. That’s major minor. Wow!”

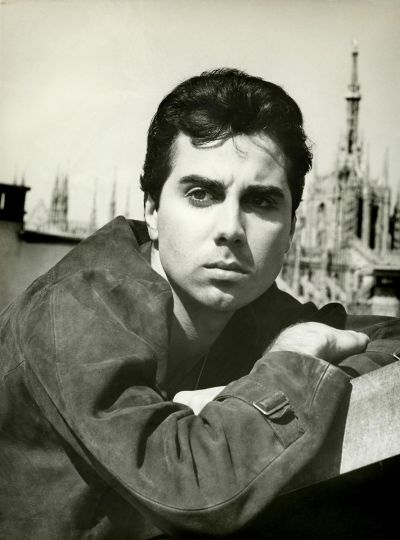

Anyone who’s met Jill Freedman knows she’s got itchy feet. No sooner did the beautiful twenty one year old blonde have her degree than she set off to Israel, land of her paternal ancestors. By ship, of course: “I’ve always preferred boats to planes. I would have loved to be a sailor, actually. In Israel I soon found myself flat broke, so I started singing in the street and in clubs.” There followed four years of wandering through Europe: Marseille, Paris (where she sang at La Contrescarpe on the Left Bank), and then London, where she earned her living singing for two years, including appearances on the famous BBC Tonight Show. “Just me and my guitar,” she says proudly. “When the money ran out we did another show, and so on.” One of her great experiences of the time still sets her eyes sparkling: going back to the States on board the legendary Queen Mary; five days looking out over the immensity of the ocean. “It was a great period. I was beautiful and I had trouble hiding it. I’ve always loved that kind of freedom. That’s why I never married. All my life my boyfriends were always a little jealous. I always wanted to be out and about, spending time in my darkroom, going out to listen to jazz. Getting married meant staying home. Out of the question… I love men. You can really have fun with them, you know. But then they get all ardent and serious.”

When she arrived in New York in 1964 the stand-up city was entering its most culturally prolific period. The natural place to live was Greenwich Village, Ground Zero for everything creative and nonconformist, for the counterculture, and for intellectual get-togethers; a different kind of neighborhood, celebrated in both movies and photography. “I often went to the Lion’s Head, a pub where writers from the Village Voice and other local papers hung out. Real characters and marvelous talkers. After all, it doesn’t matter if a story’s true or not as long as it’s good, right?” She spent thirty years in the Village, camera in hand, smilingly discreet, checking out the trendy spots and the frenzied streets for scenes and characters. “Coming to New York is always a way of getting away from your life, from those small-town microcosms where everyone knows everyone else. In New York you don’t have to know your neighbor, all you have to do is say hi, how you doing, see you! Crack a few jokes to people you don’t even know. I liked that straight off.”

It was in the Village that she deepened her visual and literary side, developed a taste for words with a real edge to them, and an obsession with quotations: reaching into an old drawer, she pulls out four fat envelopes full of bits of paper with the ones that have marked her most written or typed on them. Hundreds of sentences, including one from John Steinbeck that partly sums up the soul of America: “In the United States the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.”

Exclusive circles

Because her pictures often treat their subjects kindly, and because they can hone in on social injustice but rarely have that “horrors of war” impact, Jill Freedman’s political commitment shows through less in them. They are not so much reactive as testimony to an upbringing that emphasized altruism. “My photos are political,” she insists, “because they give freedom a voice.” Even so, the crucial element in shaping her way of seeing was an atrocity image. Looking through copies of Lifemagazine dating from the Second World War, Freeman, then aged nine, came upon photos of the concentration camps just liberated by the Allies: “Every day when I came in from school I looked at those pictures, and I cried . . . and then I went and played ball outside. It was odd; I did that for a year. It wasn’t as though we’d lost anyone during the war. One day my parents found out [her father was a real-estate salesman] and straight away they burned all the magazines. That was probably my first experience of photography and one of the reasons for becoming a photographer. If I have a conscience those pictures certainly have something to do with it, because I’ve been obsessed by that event all my life.”

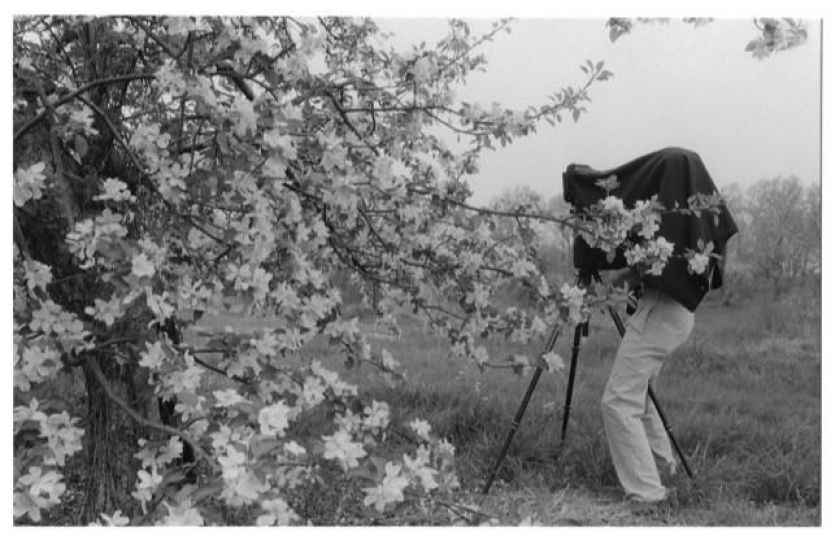

Before she bought her first camera “on a whim” in 1965, Jill Freedman was recording images in her imagination: snapshots engraved on her visual memory that were preludes to some of the photos she would take a little later on. Her subjects: the war in Vietnam, and anti-war and civil rights demonstrations. At the time she was working as an advertising editor—the only real job she has ever had—and spending every pay packet on equipment. “There was my first Nikon F, that I made love to—well, I mean, I used to give it little kisses. And then the two of us would go out for a walk.” When Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, she quit her job straight away to join the march for the Poor People’s Campaign, the last crusade King embarked on before his death. In 1971 her pictures of demonstrations, portraits of demonstrators, and scenes of police brutality came together as the book Old News: Resurrection City—but before that she had been published in Life: “There must have been five or six pictures. I remember giving my films to the magazine without really knowing what they would do with them. I even hesitated, because I was afraid they would damage the negatives. That was silly of me—they were careful, of course. It was a good thing I wasn’t on assignment, or I would have been sleeping in a hotel and wouldn’t have taken all those photos in the thick of things. I ate and demonstrated and slept with all the others, often in churches in the towns we passed through.”

Freedman has always had an instinctive preference for the inaccessible, and for slipping in amongst people she knows nothing—or almost nothing—about. It would be mistaken, though, to think that this vast curiosity—the leading attribute of her own photography and the photographers she admires—has anything to do with the voyeurism emanating from some current work of this kind. Her work has always been marked by a slightly sexy naivety which is nothing other than a profound honesty—a word that today, in an art world obsessed with challenges, can seem anachronistic. The seven books she has to her credit take us into the daily life of societies that are “closed”, at least from the point of view of the common man. Leafing through them, you can’t help thinking about the splendid sentence from Frank Zappa she once noted down: “A mind is like a parachute. It does not work if it is not open.”

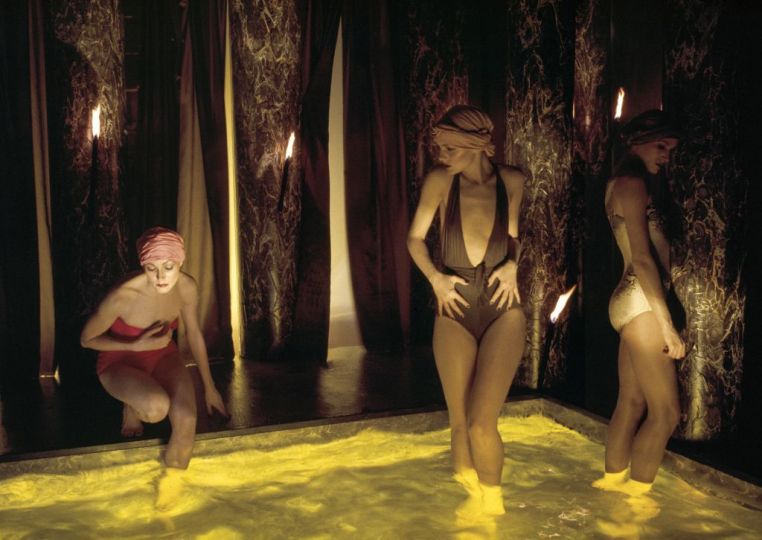

Circus Days, published in 1975, is probably Freedman’s finest book. Under the big top of the unique Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus in the Southeastern United States, the atmosphere is an indescribably magic mix of joy and drama: a crazy tale of men and animals living side by side, told in a hundred photos imbued with an incredible tenderness. A man head to head with an elephant; a clown putting on his makeup as a cat sleeps tranquilly beside him; as far as you can get from the jungle, an elephant pushing a cage with a lion inside it; and a giant hand in hand with a tiny woman dwarf. Plus a host of portraits, people whose eyes show the same mingling of melancholy and amusement. An adventure unlike any other—seven weeks of travelling and performances—that began almost on Freedman’s doorstep: “It all started when I met Cleopatra, a drag queen from the Village. A great lady. She told me about a circus where she rode elephants wearing a satin dress and a feather boa. I loved the story at once. I borrowed a Volkswagen kombi and headed off in search of a circus of my own. With the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus we traveled at night, put the tents up in the morning, on a vacant lot or behind a supermarket, did two performances, and set off that night for the next town. When I was a kid I’d always wanted to be adopted by gypsies, so I was just delighted. The circus has its own rigid pecking order, with three distinct classes: actors, clowns, and workers. But with a little bit of charm I managed to find a place for myself. I also remember not having enough money to get my films developed, so I had no idea of the result until the odyssey was over.”

Driven by curiosity and a relentless urge to understand things, Freedman then decided to hang out with New York’s firemen, a long-term project that culminated in the book Firehouse (1977). “They’re the opposite of soldiers,” she says. “They don’t take life, they bring it back.” In three different firehouses in Harlem and the Bronx, she spent two years immersed in their world: “Such handsome guys . . . But since women weren’t allowed to sleep in the dormitory, I would spend the night in the fire chief’s car. Besides, I have a rule: I never sleep with the people I’m working with.”

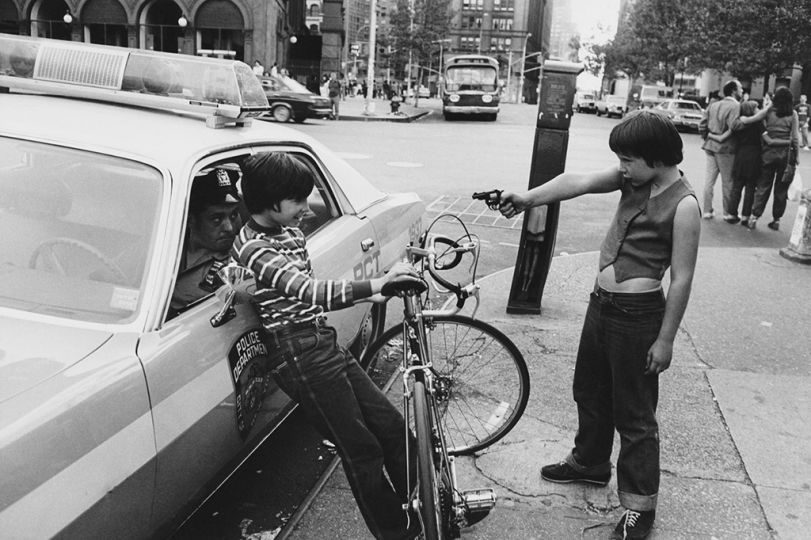

These explorations soon led to another legendary and even more inaccessible circle: NYPD—the New York Police Department. Long a critic of the forces of law and order, she now set out to “uncover their job from the inside, from a human point of view,” and at the same time “show what a good cop’s like.” The officers, some of them Vietnam veterans, called her “the liberal.” The subject matter means that the pictures in Street Cops (1982) and Firehouse, accompanied by texts she wrote herself, are more raw than usual. Night and day Freedman played the newshound the way Weegee had done before her, her camera catching the heroic, the sordid, and the bloody. She admits to having sometimes been a voyeur. But despite the oppressive atmosphere, her uncommon kindheartedness is still there, in the pictures she got of conversations, laughter, and above all rescue operations: “Street Cops was an exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, the top UK photo venue. Someone wrote in the visitors’ book, ‘Now I’ll look at them differently.’ That’s the best compliment the series could have.”

A dog’s life

One last circle, with entry denied to those not ready to love it: the Irish people. Freedman has published two books on Ireland, a country dear to her for its landscapes, its folklore and its whiskey: A Time That Was: Irish Moments (1987) and Ireland Ever (2004).

But while she is deeply fond of human beings, she prefers animals, and can talk about them with irresistible admiration. In one of her her notebooks we find a tellingly ironic line from Groucho Marx: “Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend. Inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.” When she quotes it her eyes smile as broadly as her mouth. It’s her favorite, and almost a motto when you learn that Freedman, a self-taught artist and a booklover, only ever had one real photography teacher: a certain Fang, a chocolate-brown royal poodle, “with a white rump and cheeks.” He taught her everything, she says. “When I was out walking in the street with Fang I saw everything, felt everything. He had a great instinct. He taught me how to look, because he never missed a thing. Wouldn’t it be terrific if people had as much vision and goodness as dogs?” Obviously there is a book devoted to them: in Jill’s Dogs (1993) she speaks of her unswerving love for canines, and their brotherly relationship with human beings. Funny, touching images, similar in tone to the best by her compatriot Elliott Erwitt.

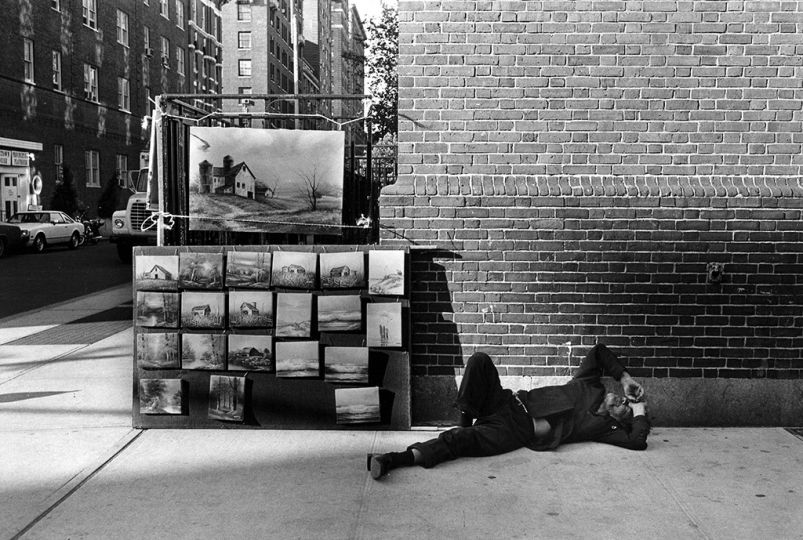

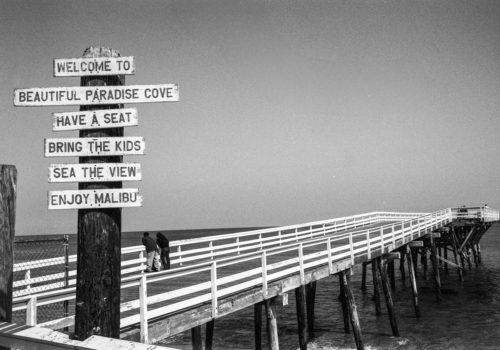

When Fang took Jill out walking, she could see. See the other dogs, sure, but also a whole lot of unsuspected riches. Beginning with all those timeless scenes, often caught with her Leica, during her wanderings on her home ground and elsewhere. Ordinary scenes with no real subject: a simple ode to existence and its special moments, be they commonplace, amusing, cultural, or iconic. A ramble through the streets against a jaunty, swinging soundtrack, with children in pride of place—as if every photo they appear in were the revelation of some eternal regret. Standing apart from her books and up until now hardly explored at all—never published or even shown—this segment of he work is now being gradually rediscovered by the artist herself: “Oh, yes . . . That naked couple on the beach, that was in the South of France. I’d completely forgotten this print. And this one of the little girl with her head out a train window.”

In the 1970s Freedman was “a star”, as Robert Stevens, photography historian at the International Center of Photography (ICP), points out. A star, true, but leading a precarious existence a bit like today. Out of conviction, you might say. Given the lack of commissions most of her meager income was going in rent; the lifestyle she had chosen came close to making her homeless. “All I thought about was my pictures, and they were all I had to live off.” At the time her economic gambit was to unpack a sidewalk “street gallery” on a tablecloth outside the Whitney Museum. “Sometimes people took my name and called me to buy a Christmas present. At $35 a picture it wasn’t expensive.” The seventies were also the beginning of photography’s rise, and Freedman was always there when the top photographers of the time got together: in a photo she pulls out of a bottom drawer she’s cavorting on André Kertész’s knees, in the company of Roman Vishniac, Joel Meyerowitz, Arnold Newman, Neal Slavin, David Hockney, and Duane Michals: “Oh, marvelous Duane. If you run into him, send him my love. It’s twenty years since I’ve seen him.” A distant memory, but one that conjures up her early sources of inspiration: Dorothea Lange’s remark, “The camera is a tool for learning to see without a camera”; but most of all W. Eugene Smith’s arrestingWounded, Dying Infant Found by American Soldier in Saipan Mountains, of 1944. “Maybe I got out of photography circles because of all those egos. Not many photographers of our time have kept their sense of humor. They’re so serious. In 1992 I moved to Miami and spent ten years reading quietly, all on my own. I rented an apartment near Miami Beach, just next door to a library that ordered in all the books I wanted. Later I became friends with Freddy, the guy who rented out the deckchairs on the beach. He was my cat-sitter when I was out of town. People [on the photography scene] thought I was dead.”

There are lots of famous incarnations of street photography and the humanistic tradition. No need to name them. Some of them haunt the photo festivals and fairs, cameras slung around their necks, paparazzi for a day, on the qui vive. In Jill Freedman’s case the legend has all but been replaced by indifference. Because she never succeeded in shaping and maintaining that legend? Because she’s always been an eccentric? Probably. But that’s not enough to explain her apparent fall into oblivion. In today’s photography world, where success hinges on knowing the right people, jostling your way to the front, and giving the public what it wants, she’s an extraterrestrial. Because she’s opted for less traveled paths and never submitted to any of the rules, her prodigiously rewarding oeuvre bears the stamp of the immaculate. It’s a kind of blunt political statement, a pure reflection of her convictions and values, and a goldmine of endlessly zany experiences. The sum total of a career that never was—which is doubtless the most extraordinary thing about it.

As Freedman never takes off her thinking cap, she’s currently working mentally on her next book. She already has the title—Madhattan—and the content is waiting to be filtered out from among all those images of the New York frenzy of her early years. She spends the rest of the time dreaming: of “crazy nights with entertaining friends”; and like everybody in winter, of sand and sun, and fine food and wine. Then there’s the dream that’s been an obsession for weeks and is about to come true next month: flying out to Costa Rica with a great writer, “the soul mate she never had.”

One thing for sure, Jill Freedman has kept a freshness lots of people find irresistible. Because love is ageless. Sometimes at night she leaves her Morningside Park neighborhood—the park itself is opposite her apartment—and goes out to listen to jazz on her own. It was on one of those evenings when she let loose a majestic tirade worthy of a Woody Allen movie: “Why am I here? A question philosophers have been asking down the ages. Why was I born? Why am I here? What’s the meaning of… What’s the meaning of meaning? Is there a life after life? You call that life when it’s raining and you can’t get a taxi?” When it’s time to leave she closes the door with that same childlike gaze, and the look of a goddess ready for another century of incredible adventures. “Make your article sexy,” are her parting words. I’ll do my best.

– Jonas Cuénin