The adage ‘a picture is worth a thousand (or ten thousand) words’, doesn’t ring true when it comes to photojournalism. The audience needs to know what they are looking at if the intention of the photograph is to communicate a specific message and derive an emotional response. Very few images can stand without captions and all images that are considered iconic have been supported by words.

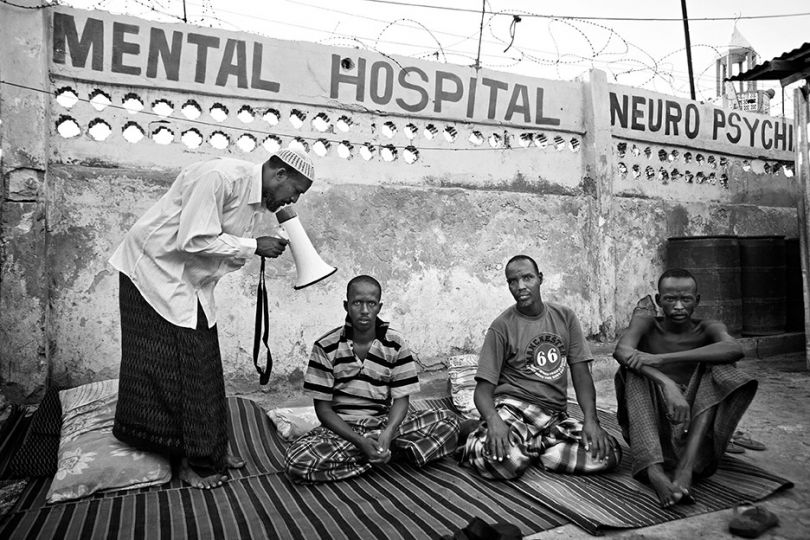

While ambiguity in photography as art may be a desirable outcome, in a journalistic context, captioning is as important to the news value of the photograph as the image itself. Cultural theorist Walter Benjamin said using captions would transform the photograph from its “modish tendencies” to beautify any subject no matter how miserable or banal, into an object that contained valuable information that reached beyond aesthetics. Only when the photograph was no longer considered an object of beauty could it become something of value.

Captions play a significant role in the communication of ideological messages enabling the symbolism of the image to be reinforced. Iconic images of the 20th Century – Dorothea Lange’s 1936 ‘Migrant Mother’ and images from the Vietnam War including Eddie Adams’ photograph of the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner, Nick Ut’s ‘Napalm Girl’, and Malcolm Browne’s ‘Burning Monk’ as examples – earned their iconic status, in part, because the captions gave literal meaning to the images, which later came to have symbolic meaning also. Lange’s photograph is representative of the Great Depression, but it is also understood to stand for poverty and injustice, the plight of marginalised women and issues of class. It also evokes the emotions of Madonna and Child.

News photographs become part of historical fact with iconic images representing the collective memory of particular events. With this in mind, the need for accurate captions is perhaps even more relevant in the digital age where the historical repository is vast and largely not curated.

It has always been an expectation that photojournalists provide captions and often detailed précis on their photographs and subjects as a requirement of the profession.

But even when photographers do provide captions, images can be misinterpreted or misrepresented once they get into the production chain of news services. Sometimes errors are simply made in the heat of the moment or the rush to get the story out. At other times captions are written to promote a particular position. In the digital sphere often the desire to get as many hits as possible, to draw attention, is the motivator. Although not all attention is welcomed as a CNN International news anchor found out when he incorrectly retweeted an image last year about the Syrian refugees.

In February 2014 the UNHCR tweeted an image of ‘Marwan’ a four-year old Syrian refugee with the caption that the boy had been “temporarily separated from his family”. The image went viral and was retweeted by the CNN International anchor with the caption: “UN staff found 4 year-old Marwan crossing desert alone after being separated from family fleeing #Syria”.

The thought of a four year-old boy being alone in the desert drew a flurry of sympathy and concern on Twitter. But once the boy’s situation had been clarified, and another photo posted to show he and a few others had fallen behind a much larger group, the tone on Twitter turned to “scepticism and anger at the perceived misrepresentation of Marwan’s plight” as The Guardian reported.

The issue here is that while the photograph with the incorrect caption may have drawn attention to the plight of child refugees caught up in the Syrian conflict, it also seeded doubt in the public’s mind as to the veracity of the report and the capacity of the media to tell the truth. The annual Gallup survey released last year showed the American public’s faith in the media is at an all time low with only four out of 10 American’s confident in the media’s capacity to report “the news fully, accurately and fairly”. A trend that is reflected in other countries including the UK, Australia, France, India and Mexico, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual global study.

Misrepresenting images through incorrect captioning is not a phenomenon of the digital age. Hubert Van Es took what is considered one of the iconic images of the Vietnam War. In 2005 in a New York Times editorial he wrote, “thirty years ago I was fortunate enough to take a photograph that has become perhaps the most recognizable image of the fall of Saigon – you know it, the one that is always described as showing an American helicopter evacuating people from the roof of the United States Embassy. Well, like so many things about the Vietnam War, it’s not exactly what it seems.” The evacuation actually took place from a downtown apartment building where CIA employees lived.

Van Es says he wrote a caption that clearly stated the helicopter was evacuating people from “the roof of a downtown Saigon building. Apparently, editors didn’t read captions carefully in those days, and they just took it for granted that it was the embassy roof, since that was the main evacuation site”. Even in 2013 the caption that ran with the photo was still incorrect – The Economist used the photograph above the lead paragraph in a story “Vietnam and America: All Aboard?” which stated the image depicted the evacuations from “the roof of an official residence during the fall (or liberation) of Saigon.”

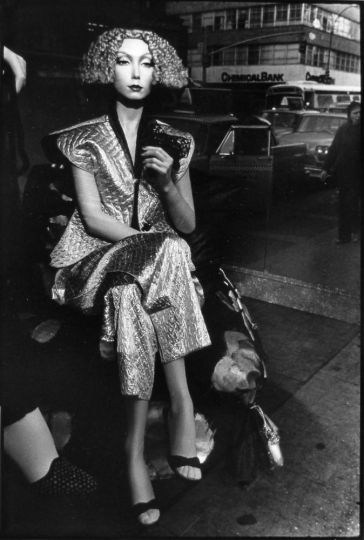

Beyond the world of news media, there are of course valid arguments for not captioning at all. Founder of Drik Agency in Bangladesh, photojournalist Shahidul Alam, used digital technology to create an immersive photo campaign, Crossfire, to expose the actions of the Bangladesh government’s enforcement agency, the Rapid Action Battalion, who were given license to capture and execute their own people without due process.

The photographs in Crossfire capture the locations where people have been killed, or from where they have disappeared. The photographs are intentionally ambiguous as Alam explained. “We withheld captions because we did not want to provide a simplistic reading of the image. We wanted the audience to work at understanding…these pictures. Behind each image there is a whole case history so when you go to the Google Earth Map you will find the exact location of each event (killing or disappearance), the case histories behind it and you can unravel the piece to a much greater level. As the viewer you are not just a passive recipient, you need to engage with it. We took this approach because we felt that this is a story that couldn’t be dealt with at a superficial level, one needed to go beneath the surface and to imagine the screaming”. Crossfire has been exhibited throughout Bangladesh and internationally to great acclaim.

Today the digital space gives photojournalists the opportunity to tell their own stories and to provide detailed captions that invite viewers to know more about what they are looking at. With an increasing majority turning away from corporatised media and looking for news and information in social media feeds and on blogs the opportunities to expand the conversation are greater than ever.

Photographs may be thought of as a universal language, but interpretation is open and dependent on the viewer’s own cultural relativism. Without captions the photographer is missing an opportunity to lead the viewer on a storytelling journey. You may not be able to control the conclusion, but you can certainly set the scene.

This article is part of a monthly series on photojournalism. Be part of the conversation. To share your ideas or thoughts on issues facing photojournalism email [email protected]

Link: Photojournalism Now

http://photojournalismnow.blogspot.com.au