With a renewed focus on feminism, not only because of the recent landmark speech by actor Emma Watson, but also other movements around the world where women are speaking up for their rights such as Ukrainian activists Femen, it seems timely to look back at the feminist era of the 70s and 80s in Australia and how photography was used to interpret, and communicate, the personal and the societal shifts of the time.

A new exhibition at Melbourne’s Monash Gallery of Art – Photography meets feminism:Australian women photographers 1970s–80s – revisits the work of 16 female photo-artists to explore themes that are still relevant today – the objectification of women in advertising; concepts of beauty; struggling for balance between career , nurturing, and equality.

This exhibition presents a unique opportunity for younger artists to gain an understanding of how photography was used to explore these universal themes and to view works that are rarely on show. It also allows insight into the collaborative flavour of that period where artists worked together sharing knowledge and talent and pooling resources.

From the 16 artists in this show I chose to interview four whose work provides a diverse canvas on which to discuss feminism – Sandy Edwards (b: 1948), Micky Allen (b: 1944), Anne Ferran (b: 1949) and Janina Green (b:1944). We talked about their work from this period, their attitudes towards feminism and how photography contributed . These photo-artists were pioneers of their time, and are still creating work today, their passion undiminished.

Sandy Edwards

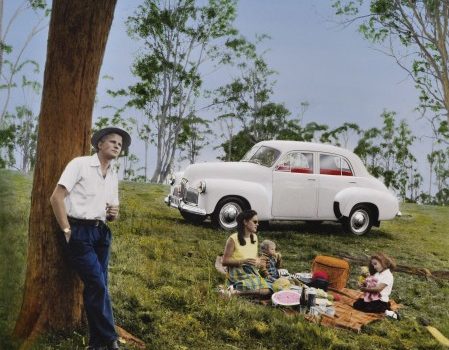

In 1983 Sandy Edwards was a member of Blatant Image, a group of female artists that were working together to change the stereotype around how women were portrayed in the media and in particular fashion photography.

“I wasn’t happy with the stereotype, but I was interested in fashion because it seemed to be a narrative outlet in relation to women being the centre of their own narrative, their own stories,” says Edwards. “We used to get together and rework images we thought were stereotype and turn the tables. By putting women in roles that men would normally be associated with we would absolutely play against the stereotypes.”

Edwards’ work in this exhibition – “A Narrative with Sexual Overtones” – centres on a collection of 100 laminated silver gelatin prints that are housed in their own wooden box and grouped into chapters. These images are largely appropriated from fashion magazines of the time and re-photographed by Edwards in black and white. Combined with text, the images create a narrative about how women were perceived, starting at the top of a woman’s head and moving down from her face along the length of her body.

“The text that runs underneath the images conveys three different voices,” says Edwards. “One is my own voice, another the voice of instruction, the pejorative voice telling women how to behave and look, and the third is the voice of abuse, using words like cunt. The words are in different typeface so you can distinguish the different voices,” she explains with a clarity that is surprising given the work was created more than 30 years ago.

In this set Edwards also used images from movies. “I took stills from books, and I used to photograph women’s faces on the television. I realised after a while that I was photographing women’s faces that were looking up into men’s faces. The men’s faces were always dark and the women’s faces always lit – they looked beautiful, but also they looked compliant, pleading, willing for love”.

“I was very interested in the roles women were playing in movies because one would identify in these movies and you were then in the hands of whoever was making the movies for the outcome. In my box set I was basically trying to come up with a positive ending through my narrative. I wanted to see women standing up against any notion of oppression, although I probably wouldn’t have used the word oppression in those days…standing up against their inner selves.”

Micky Allan

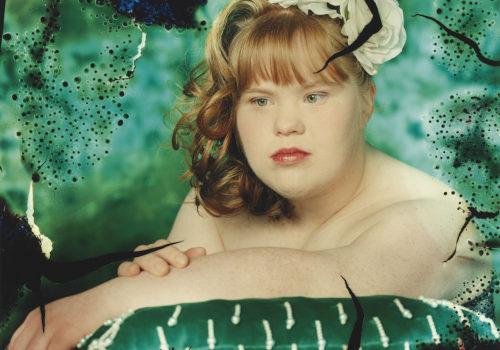

Having trained as a painter, Micky Allan was one of the first to experiment with painting on photographs, extending the concept of hand colouring with dyes by using watercolours, oil and acrylic paints as well as pencils. Today at the age of 70 she continues to work with mixed media and is currently experimenting with glass etchings laid over photographs.

The tactile nature of painting led to her experimentation with paint and photographs as she explains. “I didn’t like the darkroom very much and I couldn’t wait until the photo was ready to paint. When you touch the photograph directly, like in painting or drawing, it creates this direct link to all those little brain tremors that come out the hand, whereas in the darkroom it felt different. Because I am naturally a painter I liked the combination and the unexpected outcomes with cross overs of media”.

She continues. “I wanted to combine the fluid nature of paint with those elements of the photograph that are so peculiar to photography, like that fabulous tonal range and the fact that there is this sense that this place is real, or this event happened, or this person exists.”

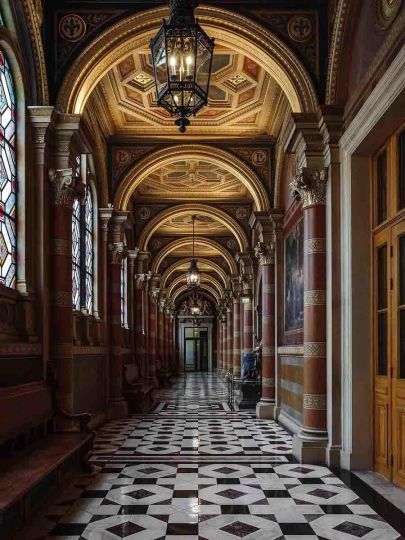

In the mid-seventies, Allan was part of a feminist art collective aligned with Melbourne’s Pram Factory, an alternate art and theatre space that provided a collaborative environment in which to create work. In this environment, artists were encouraged to push boundaries with an “anything goes” philosophy that saw some of the most exciting, and outlandish works, produced.

“In Photography Meets Feminism” there are two of Allan’s series on show – “Old Age” shot in 1976 and “Travelogue” from 1980 – showing the diversity of Allan’s oeuvre. This work she says reflects her interest in the complexity of human nature and the bigger picture.

“I’ve always been interested in that larger view of the world and how that comes through a female understanding has been part of that interest, but isn’t the only factor. There has been false categorisation of the qualities of humans into male or female, but it’s much more complex than that within each person. Even though feminism was so important at the time for giving us all a sense of freedom and the opportunity to do whatever we liked, I wanted to go into that complexity rather than through a single view.”

In her “Travelogue” series Allan’s love of mixed media really comes into play, breaking down the borders between painting and photography with some images so thickly painted that it is only after close inspection the photograph is revealed. In this work Allan has used a variety of techniques including oil, acrylic and watercolour paints as well as pencil marks, allowing her to have “a high degree of interaction with the photograph”.

“All the works in this series are named after the place where they were taken and I didn’t under expose them when I took them as I wanted them fully formed,” she says. “But I did under expose in the darkroom or didn’t develop them to a high degree because for me to actually work with the photograph it couldn’t be complete in itself. It had to be inviting and to want further development. So it was quite tricky to get a photograph just right for colouring, it was a very subtle thing. I always wanted to work really sensitively with the actual photograph, but it was creating a dialogue between the two that made something else, something new out of the encounter.”

Janina Green

Wrestling to balance her creative heart with her role as nurturer, Janina Green turned to photography as an artistic outlet in the 1980s after her daughter was born. Having worked as a teacher and printmaker before becoming a mother, Green began to use the camera to explore the dichotomy of what she felt was a dual existence.

“My photographs are quiet and reflective…they’re me musing about what it was like to be at home with a baby,” she says. “Photography allowed me to play a little and with my baby on my back I found a new release through the camera.”

An example of her work from this period is the photograph of an exquisite Chinese jardinière – “Still Life (Kitty’s Shoes On Couch) 1988. She says this image in many ways epitomises the feeling that many women had at the time, that of being split in two, being the person society expected you to be – a wife and mother – with your individual self.

“Somebody had loaned me this fancy, elegant vase and I really loved it. I’d taken quite a few photos of the jardinière, but felt it was looking more like an illustration so I put a pair of my daughter’s tiny, scruffy shoes next to it. It was an odd thing to do and that’s why I did it. To me it was reflective of my thoughts on balancing this double life.”

At the age of 70 Green is still making photographs and teaching two days a week at the Victorian College of the Arts, which she says, “entertains me a lot…Photography as art can be very political, and anything goes in that space. The conceptual nature is the thing that attracted me to photography because you have to have a reason for taking every photograph. It is a political statement before you start, before you even pick up your camera”.

Anne Ferran

‘Scenes on the Death of Nature, Scene I and Scene 2’ are two of the earliest works made by photo-artist Anne Ferran in 1986. On first glimpse these large, life-sized photographs depict what could be considered classical themes of representation, but on closer inspection Ferran’s motivation to breakdown the almost sculptural depictions of women as beautiful, calm and composed becomes evident.

“Within that framework of Classicism and Neo Classicism I was assaulting those conventions with lots of little defects,” she explains. “In a sense the fact that they were photographs, not paintings or sculptures, was already a departure from the norm. That was one way I felt I was messing with those conventions.”

These photographs were taken at a time when Ferran was spreading her intellectual and artistic wings. Coming late to art school Ferran says, “I was learning feminist theory and was very fired up at the time. I’d already had children and I felt it was important to link my developing art practice with my life as a mother – my daughter and her friends are the models in these photographs and that was very significant for me because it was a way of being able to bridge what otherwise might have been a pretty sizeable gap”.

Printed at life-size these photographs allow the viewer to see the imperfections that defy the conventional notions of beauty. “Even though they were young and beautiful they are real people, not idealised. You can see the tan marks from their swimming costumes, and bitten fingernails, ears piercings, all sorts of things that don’t tend to happen in painting or sculpture. I made all the costumes myself, so they were very rough and ready approximations of things in terms of classical flowing draperies, but mine had seams showing and they were fraying. All of that became a vocabulary for the work. But I also wanted them to be beautiful, to conform to everything you would expect of that kind of work at first glance and then when you look more closely you would see there was something else going on”.

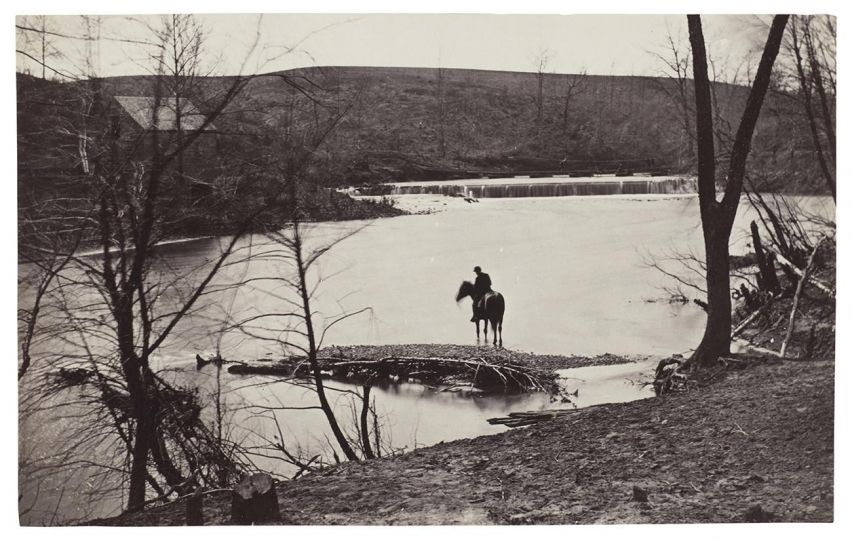

While this work is representative of her approach in the 1980s, she says “I got to a point where I started to question the efficacy of working at that level… I became interested more in contemporary events, things happening in my lifetime, and made work around that, installation work that hasn’t survived. In the mid-1990s I started to look at Colonial history and began thinking about the past in relation to how I experienced my life and my place, and what it meant to be Australian. So it was that intersection around feminism, that was still strongly present, and the idea of how do we deal with the past that we’ve inherited, that started to shape my work”.

“I’m in my sixties and the work I’m creating now looks different, but I can see the connections happening from the really early days and that is really satisfying,” she concludes.

Artists: Micky Allan, Pat Brassington, Virginia Coventry, Sandy Edwards, Anne Ferran, Sue Ford, Christine Godden, Helen Grace, Janina Green, Fiona Hall, Ponch Hawkes, Carol Jerrems, Merryle Johnson, Ruth Maddison, Julie Rrap, and Robyn Stacey.

EXHIBITION

Photography Meets Feminism: Australian women photographers 1970s–80s

Until 7 December 2014

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road

Wheelers Hill

Melbourn

Australia

www.mga.org.au