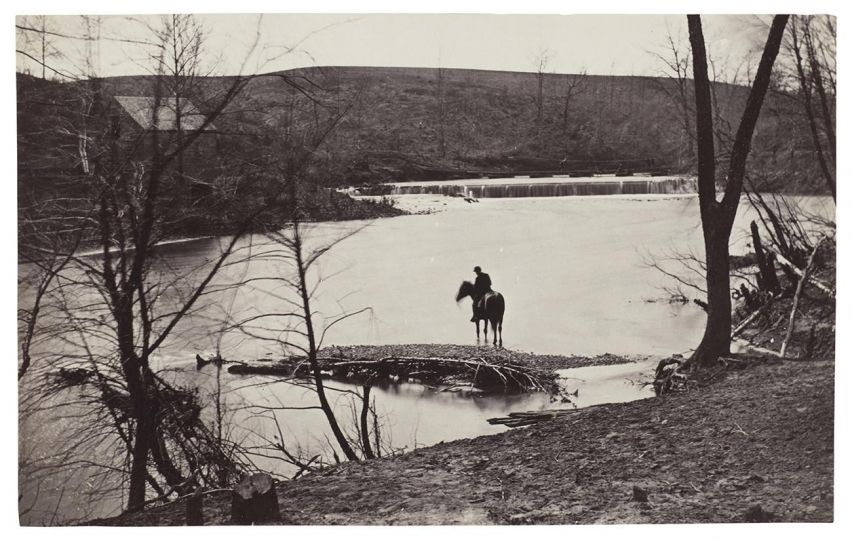

In both his life and his work, photojournalist Jean-Pierre Laffont is the ultimate expression of American freedom—freedom in his unimpeded documentation of society’s ills and the impassioned descent of an American people exercising freedom of their own. In no other country could Laffont have accessed such a wide range of controversial subject matters. For a photojournalist, America was, and continues to be, a Photographer’s Paradise: Turbulent America 1960–1990 (Glitterati Incorporated).

Driven by his own insatiable curiosity, Laffont traveled all fifty of the United States to document a broad swath of the country’s fabric. Laffont captured America through some of its most turbulent eras—seminal moments that may now even seem commonplace but were revelations at the time. The book is organized by decade, taking us across the nation, from the funerals of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy to the Washington D.C. protests against the Kent State killings, Laffont is witness to history as it unfolds before his camera.

Jean-Pierre and Eliane Laffont sat down to speak with us about the inspiration for creating Photographer’s Paradise. Eliane Laffont recalls, “Jean-Pierre and I collected from different warehouses all of his work produced over the last fifty years. These boxes contained his life’s work, starting when he was a young photographer in Algeria in the late 1950s through the end of the year 2000 in the USSR. Fifty years of work where all the worldwide major events were covered.

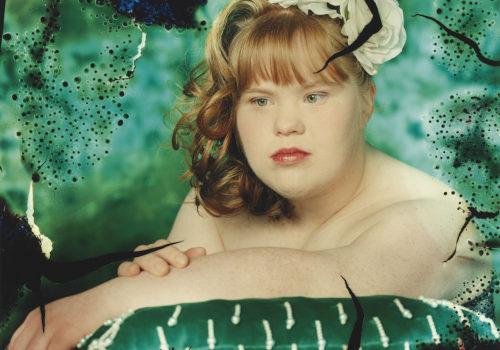

“Jean-Pierre had traveled the world, developing reports that we called at the time, ‘News Magazine’ as they were news related stories photographed at great length. He covered the opening of China to the Western world, social issues in India, agriculture in the USSR, published his famous essay ‘Child Labor,’ raising awareness regarding the subject around the world… but while Jean-Pierre was most famous for his international stories, I really wanted to show his much less known work on the US.

“For me, that was the part that interested me the most. Jean-Pierre had arrived to the U.S. in 1965 as a young photojournalist and was shooting then the first of everything: war demonstrations, ‘Hair’ in the park, Gay Pride, rock festivals, women liberation, Earth Day, Apollo XI to the moon, Apple, always in the front row at many events. While traveling around the world for the next three decades, he still had never stopped photographing current issues and social events in the US. When I started to look through his contact sheets, I re-discovered his early work: the Women’s movement, the gay liberation, the demonstrations, many important issues of the 60s and 70s. The end of the war in Vietnam. The recession of farmers in the 80s. I then realized that we had an amazing potential book on Jean-Pierre’s unknown work in the U.S.”

Jean-Pierre Laffont observes, “It was a great pleasure for me to go back to my work from the 60s. I had forgotten that I had taken some of the pictures myself. Going back through the contact sheets with Eliane made me realize that as a young reporter not only did I cover it all, but more importantly what I had photographed no longer existed and had become historical photos. For example, my work in NYC and 42nd Street— New York is a totally different city now.

“Same thing with a photo I had taken in a prison, or the return of Apollo XI. The rise of Black Power, and my photo-coverage of the Ku Klux Klan. These photographs also made me realize that I was very lucky then, working in total freedom I could probably not work with the same freedom today. Also, most of my work had never been published, and therefore was as new to me as it would be to everybody. Taken together, these photographs all show what became not only a personal, but also historical portrait of this country that I love.”

The process of editing was intense. Eliane Laffont speaks about the time spent in the archive preparing for the book: “At first it seemed such an enormous amount of boxes containing a mix of slides, contact sheets, vintage prints, negatives, magazine clips, maps, private journals, letter of accreditation, badges and passes of all kinds… It was an extremely enormous and challenging feat to achieve. First, we needed to catalog, organize, and classify… Then came the exciting part, the editing part. When doing so, you’re really trying to capture the photographer’s mind, follow what he’s trying to say. In the case of Jean-Pierre’s work, he likes to construct stories as opposed to individual photographs and displaying them next to each other. It was fascinating to reconstruct his images around the stories that he is telling. It made for a very compelling editing process, as well as intellectually challenging.

“Because I had edited Jean-Pierre’s work 40 years earlier, it was doubly challenging to edit it again. I looked over with great emotion at the red marks that I had made previously. I began to realize that at the time, I was focusing more on the news part of the story and sometimes neglecting a detailed or more personal approach. What I thought was a news story became at the second editing more of a lyrical essay. His eye was not objective after all. What Jean-Pierre was shooting was really his America. He liked to stay a long time photographing a story (as he did with American farmers, two years) so I had massive material to delve into and greatly enjoyed his personal, sometimes provocative, always emotional approach to his work. I tried to follow Jean-Pierre’s inspiration and loved watching how he developed his own style, and I now think of his work as both poetic and journalistic.”

Jean-Pierre Laffont recalls his first introduction to Glitterati Incorporated, publisher of Photographer’s Paradise: “For many years, my friend and world famous photographer Douglas Kirkland told me many times that he was curious as to why I was not putting together a book. Over time, he became more pressing. Douglas puts out a book about every two years, and he became slightly furious that over the 30 years he had known me, I had not taken my work as seriously as he felt it deserved. I was always humbled by the fact that Douglas liked my work so much. So one day with Eliane, we started putting prints together, made a portfolio and started looking for a publisher. Douglas and Françoise Kirkland then recommended Glitterati. Despite having made a list of ten publishers I wanted to see, Glitterati was now at the top of the list because of their suggestion.

“We went to see Marta Hallett, as she was the one from Glitterati that the Kirklands pointed us to, calling Marta “publishing heaven.” When we first met Marta, she had her office and her apartment in the same place. Her dog was with her on the sofa, and you could hear the office staff giggling in the next room. The atmosphere was so friendly that I felt comfortable right away. I am shy, I do not like to show my work, and I only came with Eliane because the box of prints was large and I did not want her to carry it by herself. Meeting Marta was love at first sight.”

Eliane Laffont remembers, “I had met Marta with the Kirklands once before, and I was very impressed by how close she was to the photographers she worked with. In that case it was Douglas. We had a wonderful evening at his show, then at the restaurant. My first intention was to go and see the 10 publishers that I had listed, but from the moment we entered her office-living room, she took over, and she made the decision to do this book on the spot. That totally took me by surprise. I’ve worked with many many editors and publishers throughout my career. None of them have Marta’s presence and warmth, and also energy and drive. She is fun, friendly, knows what she wants and if she wants it, it’s hers. So, when she put her hands on Jean-Pierre’s photos and said to us after only 20 pictures, “I love it. I want to do this book, it’s mine,” I was totally convinced that she was the person we were going to do the book with, and it never crossed my mind after we left the office to call the others on my list. Marta had spoken from her heart, and clearly was doing what she wanted because she enjoyed it. No balance sheet, no projection, no business plan— very unusual these days where business always takes over and has the last word.”

With the release of the book, Jean-Pierre Laffont reveals, “I am in awe now that I have the finished book in my hands. The final product is not what we started with when we first drafted the contract. The book was supposed to be an estimated 160 pages, measuring 10”x12”, with approximately 150 photographs, and 7,000 words. Two years later, now that the book is completed, it measures 10”x13.5”, has 392 pages, with 359 black & white and color photographs, and more than 30,000 words. I do not know many publishers who would offer a photographer more, much more, than what they had signed for. It is a big, beautiful book and I’m very grateful to Marta for her determination to produce such a magnificent, large body of work. To both Marta and Eliane, a big Thanks. I owe them so much, I could not have my Paradise without them.”

http://glitteratiincorporated.com/products/photographer-s-paradise-turbulent-america-1960-1990-by-jean-pierre-laffont

http://www.jplaffont.com