Photo Poche is celebrating its fourth decade of existence this year, an opportunity to look back at the history of this reference collection that has democratized access to photography.

The Photo Poche collection was born in a climate of effervescence for the arts. One year earlier, in 1981, François Mitterand was elected president of the Republic and appointed Jack Lang to the culture department of his socialist government, who was to initiate essential changes for publishing and photography. He introduced a fixed single price for books and created, in 1982, the École nationale supérieure de la photographie in Arles as well as the Centre national de la photographie (CNP) in Paris, which he entrusted to Robert Delpire, a great advocate and publisher of photography.

At the head of the CNP, Robert Delpire, aware of the public’s growing interest in photography and the need to democratize access to it, imagined a new type of collection with Photo Poche. Each issue offers a retrospective of the work of a photographer or a part of the history of photography, all in a small and inexpensive book, which does not neglect the quality of reproduction. The issues are largely illustrated in order to have a complete access to the work of an author, and are accompanied by a critical text, sharp but accessible. For Géraldine Lay, in charge of this collection since 2019, from the beginning, the strength of Photo Poche has been to constitute “a useful tool for both amateurs and specialists.”

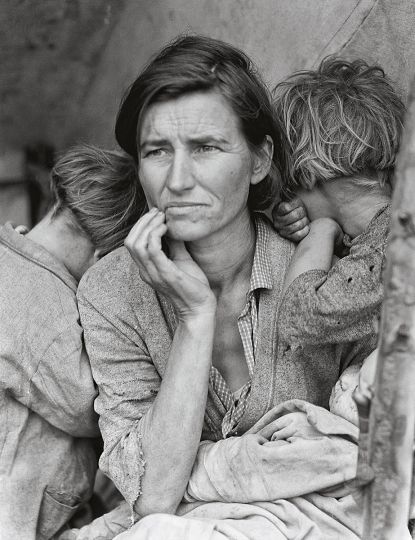

The first issues are dedicated to the great names of photography: Nadar, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Robert Doisneau, Nicéphore Niépce, Eugene Smith, Robert Frank. Several thematic issues were also published, devoted for example to the great photographic survey of the 1930s by the FSA in the United States, or to the magazine Camera Work. The public was immediately won over and sales reached the thousands. The collection was taken over by Nathan in 1997 and by Actes Sud in 2004.

If at the beginning of Photo Poche some photographers were reluctant to lend themselves to this singular format, most of them now hope to be part of it: “to be published in this collection has become the sign of the consecration of a work. On the readers’ side, Photo Poche has acquired a cult status and attracts “a public of collectors”. For Géraldine Lay, this is a step away from the original ambition, which was to be popular. In order to attract a wider and, above all, younger readership, it was decided that a new graphic identity would be created for this fortieth anniversary.

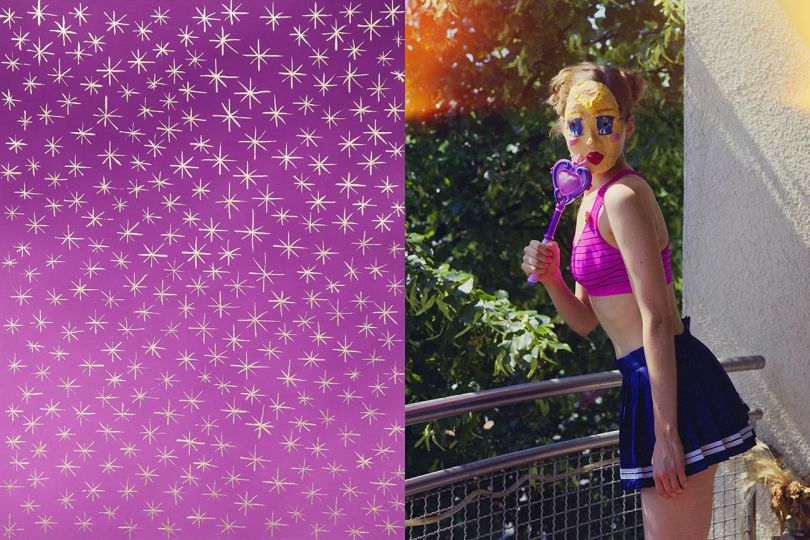

The new identity, entrusted to the graphic designers Wijntje van Rooijen and Pierre Péronnet, works according to “a principle of balance between heritage and renewal” and allows a more pleasant reading of Photo Poche, thanks to a reduction of the information on the cover, a clearer typography as well as, major change, the choice to replace the black background by a white one in order to let the images breathe. On the cover, this new background is bordered by a colored border and the name of the photographer has gained in importance compared to the previous editions.

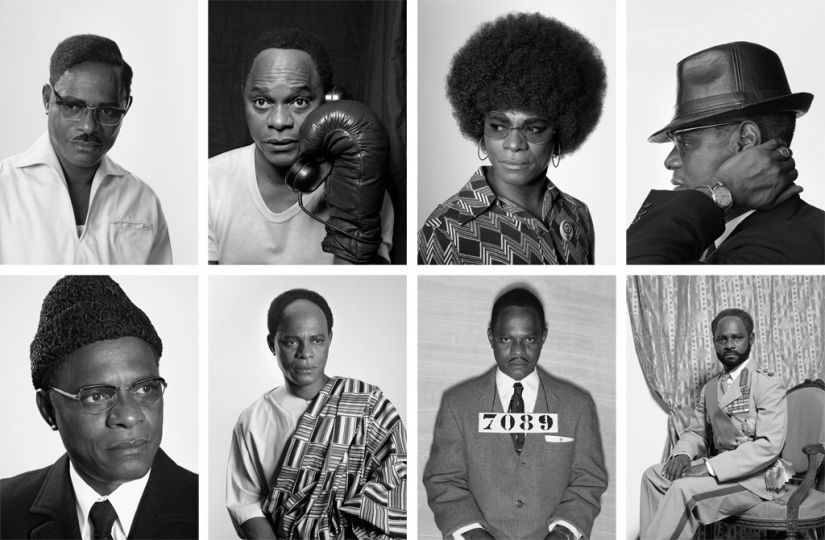

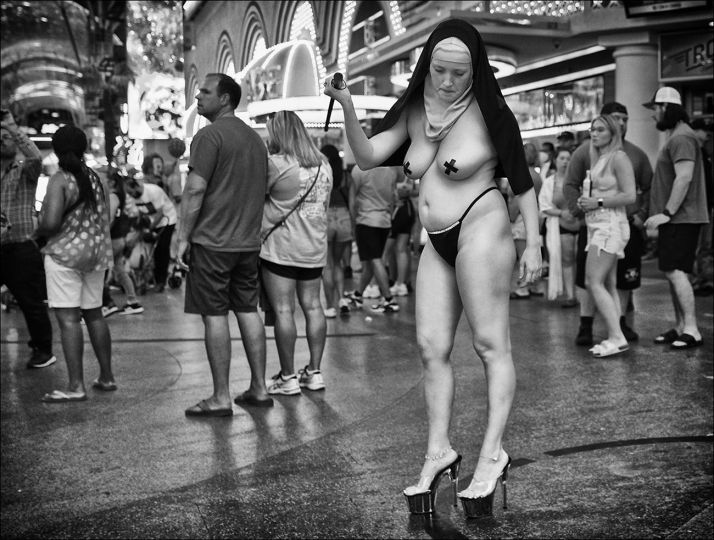

The arrival of Géraldine Lay at the direction of Photo Poche has also brought a geographical opening in the choice of the published photographers, as well as the will of a greater parity. In line with the issues dedicated to vernacular photography, autochromes, scientific or post-portem photography, she also intends to continue to highlight alternative photography practices that are “at the heart of the questioning of contemporary photography at the moment.”

The first issues of this new edition are a real success. Beautifully designed and open to the future, Photo Poche still has many beautiful years ahead of it.

More information