Dove Allouche, making marks on a new scale

Dove Allouche has devoted some twenty years to an in-depth study of inner and outer spaces. He draws on a range of means to survey tangible abstractions of space and time ,with various scales and depths, foregrounding new indices of perception in the images he creates. He initiates inward or outward journeys through land, stars, forests and specters, probing minerals for analogies with our own states of being, discarding longstanding notions of history.

Allouche installed a scale model of Peter Freeman gallery in his Parisian studio and has, for several months, as if in insomnia, has been shifting the positions and interactions of the scaled down works to be exhibited. The final selection offers a reading of a state of circulation between the infinite beyond, the infinite within, and the milieu in which phenomenons appear in imagery. The exhibition features works from three recent series.

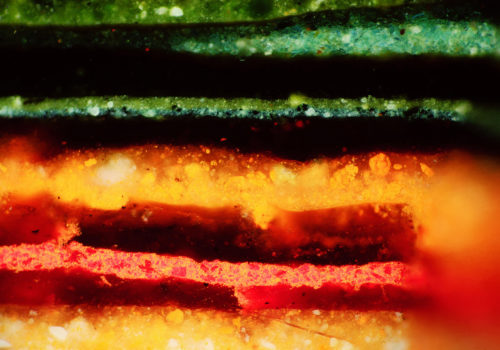

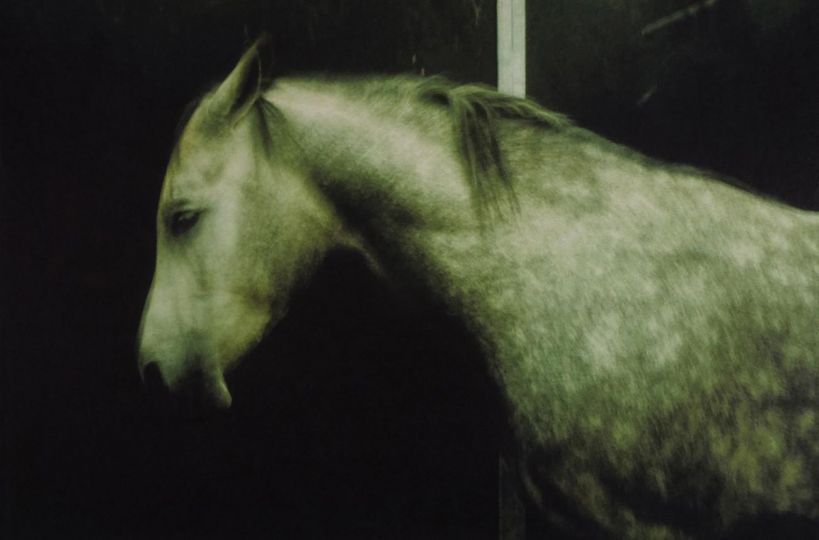

Absorption Lines (2018-2019) is a series of platinum prints that break light signals down into vertical shadings of gray. The Repeint series (Repainted, 2019-2021) consists of photographic enlargements of samples of layers of paint taken from works of the Italian Primitives in the Louvre, while drawings from the I.R series (2016-2018) were chosen for inclusion in the exhibition from 153 drawings in silver oxide, based on the entire corpus of 153 glass plate negatives left by Isaac Roberts in what was the first ever attempt to capture the surface of stars using photography (1883-1885).

The Absorption Lines and Repeint both reflect an index based distance from the object showcased in the work, either hugely enlarging a tiny fragment or bringing the vastly distant close by means of optics. Such points of view are possible thanks to the telescopes and microscopes that bring objects in their sights into the realm of the visible, and to photography, which creates a photo-reference for the objects in question while also foregrounding what they have in common. Printed in identical formats, the photographs of microscopic objects are visually equivalent to the vast objects reduced to the dimensions of a single photograph, echoing Heraclitus’s statement that the sun is the width of a human foot.

Dove Allouche does not see making the invisible visible as a way to seek the beyond elsewhere. It is not a meta- physics but a physics of bodies that determines the relationship to objects and steers the process by which images are revealed. Applying a filter to the as yet unseeable is how he makes discoveries and adjusts the scale of visibility, to obtain a new image of something that had no prior visible appearance. His creative practice involves traveling to selected sites, to the remotest reaches of the earth if needed, or peering down a microscope, generally in the company of experts best placed to present the angle of research. He then specifies the object, frame, line of action, protocol, and means of image production. In this case, the Repeint series involved taking minuscule samples of paintings of the Virgin in a laboratory, studying them with optical instruments, analyzing them from various angles, selecting choice fragments, thinking about how to present them in image format, experimenting with various sizes of print, and eventually, via the magic of alchemy, creating new indices at the limits of the physical properties of solid bodies.

This is the substance of Dove Allouche’s alchemy and indices. Under his lens, the fragments sampled from the layer of paint reveal qualities that visually echo their pictorial origin – coverage, varied granulosity, sedimented strata.

The depth of the brush stroke reduced to a single dot visually generates the indices of the overarching movement. Enlarged a million-fold, the fragment of paint still evokes the painting’s slow, layer-by-layer constitution, prompting us to imagine the artist’s hand applying the color, by turns hesitant and bold. The paint is not applied equally or uniformly. The minuscule fragment hints at micro-pauses, hesitations, renewed confidence, as if the brush stroke could be subdivided indefinitely, each moment offering a glimpse of its genetic code. It gives visible form to the hand behind the brush and its experiences of a host of inflexions, accelerations and pauses in every micro-moment, holding the entirety of a thought.

The temporality of a brush stroke can be read as the extent of a body, however infinitesimal. This limit of amorphous matter triggers the tangible sensation of a frontier zone opening onto undifferentiated time and space, as if they formed the circumference of a single circle on the horizon. This indissolubility results from a process of reduction that is a recurrent feature of Dove Allouche’s creative practice, bringing spatial and temporal distances back to a common dimension rooted in proximate perception. Thus reduced, distances measured in geological eras (as far back in time as possible), by the surface of stars (as far away in space as possible), and in the depth of particles all move towards assimilation within a single body—the body of the image. It becomes clear why the concept of a light year can express spatial distance with a time unit.

* * * *

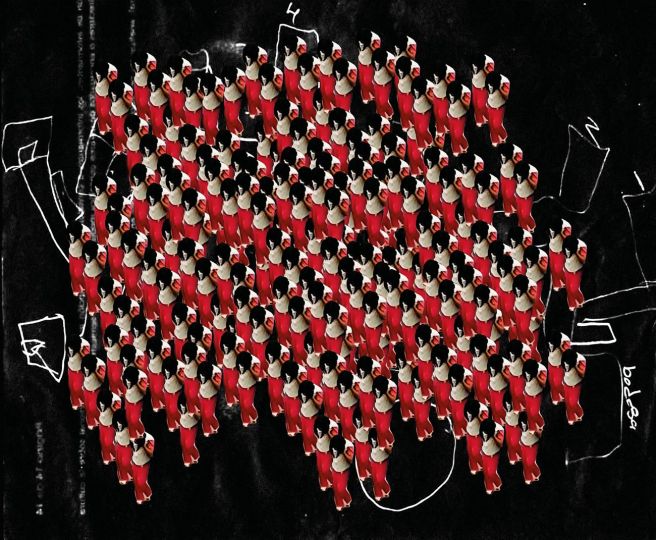

When Dove Allouche took Isaac Roberts’s photographs as models for his own drawings after more than a century since their original execution, he simply drew what he saw—not a star, but what he saw in an image measuring 10 x 10 cm, distanced from its own model and marked by emulsions and the passage of time. The scars of time reveal the resistance that imperfections put up against quasi-monochromes, a resistance heightened and foregrounded by their inclusion in the drawing. What makes the image is the insistent return to the apparent same object and the repetition of a creative act whose secret purpose seems to be ritualizing the process of testing images against their own motifs and arguments, as if repeating endlessly I am not who I am.

Several thoughts follow without demonstrative order, swimming upstream towards the genesis of his images:

On Isaac Roberts’s nebulae: when photography and its potential uses were invented, capturing the surface of stars on a glass plate meant ushering a new relationship between what could not be seen and what now became visible. But what did become visible was not so much the reality that was imagined as what became the image itself. Roberts sought to photograph the surface of stars and long obtained nothing but views that failed to reach the threshold of discernibility. Rather than a distinct object, his plates show a fragment of atmosphere awash with tones of gray, casting a veil that fails to free what he sought. The only clearly legible element is the writing, added later, giving the date, latitude, longitude, and universal time of the viewpoint.

Interestingly, Roberts stubbornly repeated the experiment 153 times, methodically sweeping the heavens and pinning down fragments like pieces from a jigsaw of the vast night sky.

The 153 pieces of sky are Dove Allouche’s starting point. The images stranded on the plates become the object, replacing Roberts’s aim. The works no longer seek to capture stars that cannot be seen, but become a drawing project. Whatever subject inspires it, or whether it aims to be a faithful rendering, the drawing detaches itself from the exteriority of its model and becomes its own object, with its own space, time, and singularity, such that the apparent resemblance between it and its origin becomes a mere evocation, showcasing the gap between objects and the intentions behind them. Even if we could see what we had the idea of seeing, this is not where we would find what we are looking for (in images).

Dove Allouche steps into the image as if they were the depths of time. For drawing, neither matter nor event is negligible. Every detail, even the slightest trace of grease, is minimalistically brought to a point of equal presence. A failed, deteriorated photograph can become the model for a full-fledged drawing.

Dove Allouche deconstructs our perceptions and leads them back to basics, freeing them from their bond with time while rooting them in the present. In the subtext of his images I hear species loss, increasing entropy, the eclipse of the self. Unsettling analogies between states of the visible, scales of space and time, foreshortened perceptions: prehistory, the mineral era, the dawn of life, species differentiation. What I see dominating the major threads of his work—without ever taking an in-your-face approach to ecology—is an intuitive feel for analogies between states of the world, placing targets in the far distance, so remote that they avert the panic of belonging to our time. Dove Allouche lays down lines of questioning, establishes fields of perception and visual correlations, regularly looping back to the foundational elements, be they real, imagined, or conjured up in a haze. He follows the thread of the elements, the bodies they form, the broken succession of their imperfections. In so doing, he holds to and preserves the consistency of the bond between what we see and what we do not see, enough to support and maintain for years on end the transfer of one view to another, in the way we might move a mountain stone by stone or shoot at the stars.

Our distance from ourselves is as incommensurable as our distance from the stars.

Tristan Cormier

Dove Allouche : Primordial Soup

13 January – 26 February 2022

Peter Freeman, Inc.

140 Grand St, New York, NY 10013

www.peterfreemaninc.com