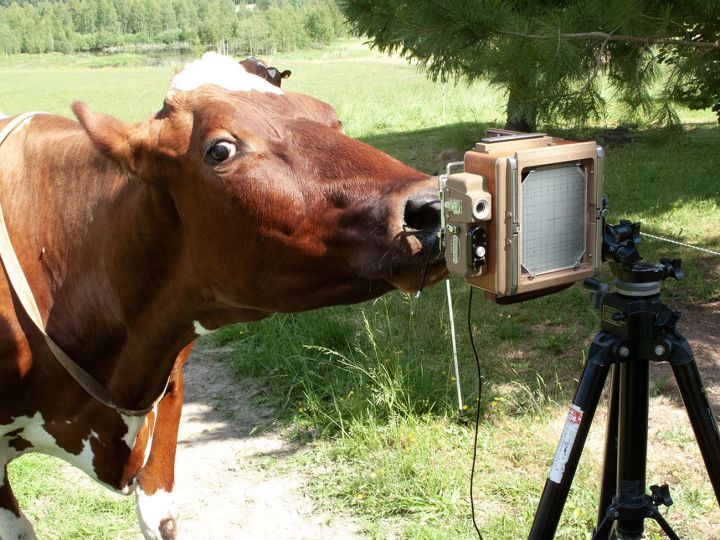

This year’s $5,000 Howard Chapnick Grant was presented to Pete Brook for his project, A History of Prison Photography, Written by Prisoners. The grant is awarded to an individual for their leadership in any field ancillary to photojournalism, such as picture editing, research, education and management. For more than a decade, Pete Brook has written about and curated images of mass incarceration in the U.S. For this project, Brook is teaching the history of photography to 28 men in San Quentin State Prison, California.

“Together, we’re analyzing scores of existing images of lock-ups. In accumulation, we’re creating a prisoner-centric visual critique of the Prison Industrial Complex.” says Brook. “It’s an honor to be a recipient of the Howard Chapnick Grant, an award that has championed people-focused pedagogies. I stand in solidarity with prisoners, their families and returning citizens, but I do not have their experience and insights. They are the experts. If, as a society, we’re to halt the failings and abuses of mass incarceration we need to hear prisoners’ voices.”

“Pete Brook and the incarcerated students he has enlisted in this project are creating a history of photography within the U.S. prison system and a curriculum of study that has never been done before,” said Brian Storm, founder of MediaStorm, Smith Fund board member, and Chair of this year’s adjudication committee for the Chapnick Grant. “The research and production by Brook on this topic are absolutely fascinating and represents the very essence of the Chapnick Grant.”

Project Description(submitted by photographer):

A HISTORY OF PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY WRITTEN BY PRISONERS

Incarcerated students and I will co-author “History 101: Photography In American Prisons’, a course curriculum on images in, and about, carceral sites in the United States.

For a decade, I have researched, written about, and curated images of the American Prison Industrial Complex. I have had the benefit of many resources—free movement, unlimited and uncensored communications, a modest cultural capital, professional allies, inter-library loans and special collections access. Incarcerated persons don’t have the same access to people or knowledge. While I have visited and volunteered inside prisons in the past, I remain an outsider to the system. While I stand in solidarity with prisoners, their families and returning citizens, I have not the insight of men and women subject to the prison system. Nor have I the experiences of years of surviving the system, as prisoners’ loved ones have. I would like to acknowledge this difference and address its tension. I’d like to share the resources at my disposal.

There is no publicly available curriculum on the history of photography in the prisons of the United States. I could write one. We, I’d prefer, will write one.

I will work as a guest lecturer with the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison for a period of 15 weeks (two 2-hour classes per week) from September 4th-December 14th, 2018. In the first 5 weeks, I will teach a course that delivers a survey of image-making from within U.S. prisons–from the earliest connections between social justice and prisons during the civil rights era by Danny Lyon and Bruce Jackson (1960s) to the relative free reign forays into prisons by Morrie Camhi, Eve Arnold, Taro Yamasaki and others (1970s); from news coverage of pressure-cooker facilities (1980s) to artists’ incorporation of audio and text and collaborative practices in genres such as collected prison visiting room portraiture, prisoner-made photos, photo-performance (1990s); and from surveillance leaks and evidence photos to newly available technologies used by activist networks (2000s).

In the following 10 weeks, we will, as a class, revisit the material and synthesize it into a curriculum weighting photography projects that–according to the students’ decisions–are most instructive for a general audience. The curriculum that prisoners and I will put together will be a significant contribution to the literature on the visual culture of imprisonment; it will focus on themes that they draw upon together. Images can be proxies for experience and the students’ experiences will inform the narrative.