Catherine Edelman Gallery from Chicago presents works by Frieke Janssens, Gregory Scott, John Cyr and Keliy Anderson-Staley.

• Frieke Janssens: SMOKING KIDS

For decades society was accustomed to seeing people smoke cigarettes in advertising campaigns, television sitcoms, and mainstream Hollywood movies. The sight of a cigarette was as common as a family dinner. Many mothers of baby boomers smoked during pregnancy, well before the surgeon general declared it harmful. Virginia Slims sponsored women’s tennis, and the Marlboro man and Camel Joe became American icons. Today, cigarettes are banned on airplanes, in restaurants and bars in cities throughout the world. At the same time, there has been a resurgence of allure associated with smoking, as can be seen in one of the most beloved shows on television, Mad Men, which celebrates the era of cigarettes and martini lunches.

Frieke Janssens embarked on Smoking Kids in response to seeing a video of a chain-smoking toddler in Indonesia who became a tourist attraction. Alarmed by this reality, she decided to show people what the act of smoking looks like through the posturing of four to nine year old children. Working with modeling agencies, volunteers and family friends, Janssens tackled the issue of glamour often associated with smoking. Both irreverent and stunning, Janssens’ photographs challenge our perceptions of smoking and the attitudes often defined by it. As the artist states:

“A YouTube video of a chain-smoking Indonesian toddler inspired me to create this series. The video highlighted the cultural differences between the east and west, and questioned the notion of smoking as an adult activity. Since adult smokers are the societal norm, I wanted to isolate the viewer’s focus on the issue of smoking itself. I felt that children smoking would have a surreal impact upon the viewer and compel them to truly see the act of smoking rather than making assumptions about the person doing the act. Coincidentally, around the time I was making Smoking Kids, a law passed that banned smoking in Belgian bars. There was an outcry from the public about government intervention, freedom being oppressed, and adults being treated like children. With health reasons driving many cities to ban smoking, the culture around smoking has a retro feel, like the time period of Mad Men, when smoking on a plane or in a restaurant was not unusual. The aesthetics of smoke and the particular way smokers gesticulate with their hands and posture cannot be denied, and at the same time, there is a nod to the less attractive aspects, examining the beauty and ugliness of smoking.“

It is important to note that chalk and sticks of cheese were used as props for the cigarettes, and candles and incense provided the wisps of smoke. The final photographic results were done on computer, combining the photograph of the child with a photograph of an adult hand smoking a cigarette. Janssens invites the public to wrestle with these hauntingly beautiful images, which both seduce and shock.

• Gregory Scott

“What if” is a good question. What if I was taller? Or fatter? Would that make me different inside? What if I was five years old? What if my body was female, or a horse, or a bird? What if the room I’m in is an illusion and the picture hanging on the wall is real? As delightful as curious exploration may be, there is something else that drives me. I want to capture the emotional states that we all have as humans; emotions such as laughter, loneliness, futility, desire, insecurity, confusion, and play. And especially moments of being that elude verbal description. How does humor make sadness more poignant? Or sadness give humor more depth? How can loneliness be so starkly personal and yet utterly universal? And why does “serious” art have to be so, well, serious? I attempt to accomplish three goals with my artwork: for it to be engaging, meaningful, and accessible. To accomplish this I build in multiple layers of interpretation. To make it engaging I explore elements of trompe l’oeil, illusions, and altered realities to entice the viewer into paying attention. At the same time these techniques explore our perceptions of what is “real.” Is a photograph more real than a painting? Is video more real even though it is low resolution? Rather than enter the well-worn discourse on photographic truthfulness, I’m more interested in the tendency for people to be convinced by an obviously manufactured fantasy.

By placing a video into a framed photograph in a gallery setting, I try to examine the conventions of art and its relevance and value in today’s world. The inherent strengths and weaknesses of each of the different media are exposed by their juxtaposition. The juxtaposition also compromises each of the media. Paintings are cut into sections, photographs are reduced to serving as backgrounds, and the video is surrounded by media that exposes its shortcomings in depicting detail, color, and tone.

In each piece, I act out moments of human emotional existence that are sometimes humorous and other times poignant. Whatever the mood, the human element provides a personal connection for the viewer. For me this is what makes the work meaningful, and where the real value lies.

Finally, it is important to me that the work be accessible. Contemporary art often obscures its intent or simply fails to communicate. I want anybody, regardless of their art knowledge or appreciation, to get something out of their experience when they see the work.

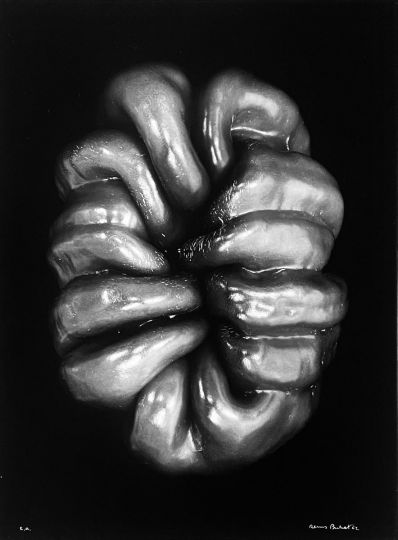

John Cyr

(b. 1981) is a Brooklyn based photographer, printer and educator. In 2010, Cyr received his MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. In 2011, he was the recipient of the New York Photo Award in the Fine Art Series category and was juror Anthony Bannon’s selection for the Project Prize in the Daylight/Center for Documentary Studies Photo Awards.

In addition to working on his own photographic projects and teaching, he owns and operates Silver 68, a traditional silver gelatin-printing studio in Dumbo, Brooklyn’s Photo District.

Artist Statement

From the mid nineteenth century until today, silver gelatin printing has been one of the most utilized photographic processes. From classic reportage to fine art photography, the majority of it was performed in a black and white darkroom until the mid-1970’s. As recently as 2000, black and white darkroom classes still served as the location for introduction to photography courses. The digital advances in photography over the past ten years have been remarkable. I am photographing available developer trays so that the photography community will remember specific, tangible printing tools that have been a seminal part of the photographic experience for the past hundred years. By titling each tray with its owner’s name, I reference the historical significance of these objects in a minimal manner that evokes thought and introspection about what images have passed through each individual tray.

• Keliy Anderson-Staley (b. 1977) was raised off the grid in Maine, studied photography in New York City and currently lives and teaches photography in Arkansas. She earned a BA from Hampshire College in Massachusetts and an MFA in photography from Hunter College in New York.

Artist Statement -Americans: Tintype Portraits

Each image in this project presents a face and is titled simply with a first name. The title of the project alludes to the hyphenated character of American identities (Irish-American, African-American, etc.), while only emphasizing the shared American identity. Therefore, although the heritage of each individual might be inferred from assumptions we make about features and costumes, the viewer is encouraged to suspend the kind of thinking that would traditionally assist in decoding these images in the context of American identity politics.

Like the photographers of the 1850s, I use hand-poured chemistry that I mix myself according to original recipes, period brass lenses and wooden view cameras to expose positive images directly onto blackened aluminum and glass. The individuals I photograph look contemporary, but there is also something anachronistic about these images—a confusion about their place in history—as if they have been detached from time, and the viewer cannot quite put them back in their proper context. Yet, with their contemporary dress, tattoos and modern expressions, they can only truly belong to the current moment. The nineteenth-century collodion process was frequently used for “scientific” ethnographic studies of the human face, many of which were based in racist assumptions about physiognomy. In using this process, I hope to make the history of portrait photography one of my primary subjects. The project draws attention to the fact that images of ourselves exist within a history of images. Our identities are linked to the visual history of social difference, a history in which photography has not always played an innocent role.

Each portrait is a fairly straightforward likeness, and my sitter knows that it is for a project, that it will become part of a “collection” of hundreds of images, but they also participate in shaping the image that represents them. These resulting images are often exhibited among dozens of portraits, portraying Americans in all their variety. Echoes and patterns of similarity and difference can be found across the collection, but each portrait reminds us of the persistent uniqueness of human faces, and the common human denominator comes to the foreground.

At the Paramount Pictures Studios, Booth 11 Stage 31