This year, Paris Photo is launching the Voices sector, which highlights a selection of artists or galleries through the perspective of a guest curator. Three curators have been invited to design a proposal based on a theme of their choice: Elena Navarro, founder of FotoMexico, has created a project focused on Latin American photography; Azu Nwagbogu, founder and president of the Lagos Photo Festival, explores how artists reclaim archives; while author and independent curator Sonia Voss examines the bedroom as a platform for expression through the lens of Eastern and Northern European scenes during the Cold War. L’Œil de la Photographie met with Voss.

Your proposal is titled Four Walls. What are its themes?

For some time, I’ve been interested in how the coercive systems of Eastern and Northern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s led artists to develop strategies that are very focused on intimacy and domestic space. These often confined spaces were transformed into genuine places of creation through the inner freedom and imagination of the artists. I find this incredibly powerful and striking even today, with diverse interpretations from one country to another. We worked with participating galleries to highlight some figures that are still relatively unknown to the general public, who represent these unique creative forms and strategies specific to these regions. Additionally, we didn’t want to confine these historical perspectives to the past but rather show how they continue to influence contemporary creation, building bridges between past and present.

Which countries are represented?

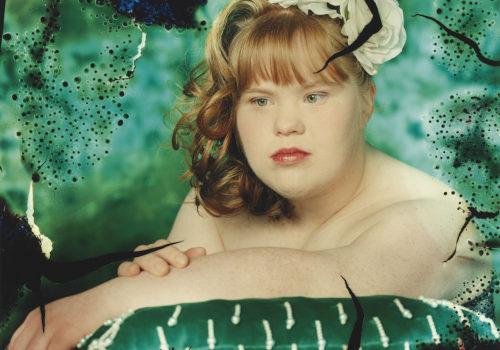

First, there is Ukraine, represented by the Alexandra de Viveiros Gallery, which has been passionately advocating for the Kharkiv School for several years. The Anca Poterasu Gallery represents Romania, featuring photographer Aurora Király and the experimental film collective kinema ikon, active since the 1970s. The Czech Republic is represented by Fotograf Contemporary, showcasing two women, Libuše Jarcovjáková and Markéta Othová. The Monopol Gallery pairs Polish artist Zygmunt Rytka with East German artist Gabriele Stötzer. Finally, Kaunas Photography presents several Lithuanian photographers. These last three galleries are participating to Paris Photo for the first time. One of the aims of Voices is indeed to open doors for new players.

All these artists employ visual strategies that subvert the coercive systems in which they emerged. In your introductory text, you mention “the sovereignty of their bodies, imagination, and, often, humor” as ways to confront restrictions on freedom. This includes staging, composition games, image intervention, and transcending the everyday. Are these strategies common across all these countries?

The more we explore photographs from these countries, the less we want to group them under a single label. Each country has a different story, including different historical events and ties to the history of photography. In East Germany, avant-garde artists left in the 1930s, and photography developed without this avant-garde foundation. By contrast, in the Czech Republic or Poland, the avant-garde remained strong throughout the 20th century. On the other hand, some countries, like Lithuania, were more deeply influenced by humanist documentary traditions. So, there are certainly common threads related to shared human experiences in the “Eastern Bloc,” but also distinct visual traditions unique to each country.

How do you view the position of Eastern and Northern European photography in the international market?

In recent years, I’ve noticed a growing presence of galleries from these regions. Institutions, in particular, are increasingly interested in these countries. The Centre Pompidou, for instance, has made great efforts to incorporate these countries into its collections. American collections are also paying close attention to these chapters in the history of photography.

Could you present some of the works in the exhibit?

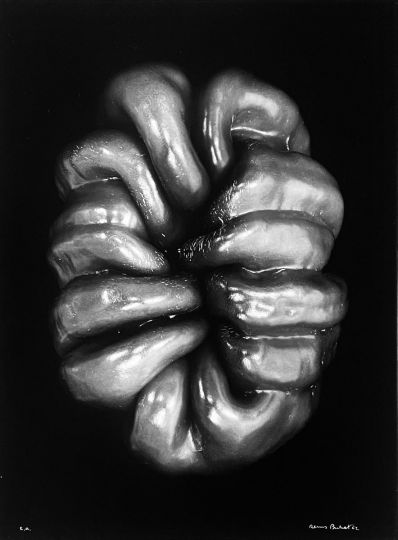

One example is Roman Pyatkovka, represented by Alexandra de Viveiros. His work beautifully exemplifies how these artists turned their intimate space—their “home”—into an experimental playground, a laboratory. Pyatkovka created experimental photographs of nude bodies—which were banned at the time—onto which he projected images of official Soviet parades. From his bedroom, he built a multi-layered world, combining bold formal experimentation with an open critique of the regime. Another striking example is the work of Libuše Jarcovjáková, whom some may have discovered at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2019. She lived and worked on the fringes of Czech society for a long time. For her, the domestic space, a place of retreat, became a theater of intimacy where she staged herself with her friends in the simplicity and exuberance of her private life.

More informations :