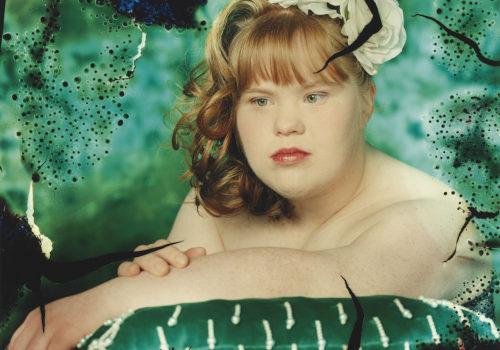

He signed 101 LIFE covers and it’s impossible to count the number of people he has portrayed, always in a way that captured their character, charisma and depth of soul. Often with a subtle irony that makes his images topical. Philippe Halsman. Lampo di genio, the retrospective exhibition dedicated to him at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, presents over a hundred images that trace the life and the creative work of this author, whose style is both lucid and visionary, using a highly refined photographic technique, but also collage, disenchantment and that touch of the absurd typical of the avant-garde and, above all, surrealism. In this way, he has created extraordinary portraits, conceived as true artistic performances.

One example is the renowned Dali Atomicus, in which the artist is portrayed painting (and jumping, but we will get to that later) as the studio world seems to swirl around him, capturing the surrealist vein at its best. And if you were lucky enough to have Halsman’s daughter, Irene, illustrating his work, you would also find yourself in the vertigo of the vortex, amidst buckets of water and flying cats (Irene was in charge of drying them off and feeding them with excellent sardines after each shoot). Dali and Halsman (as well as Yvonne Moser, Halsman’s wife, and four assistants) worked together to make the shot. The desired result came, as Halsman himself wrote “six hours and twenty-eight takes later” with subject, photographer and staff wet and exhausted; “only the cats looked as good as new”.

“My life was always interesting because I never avoided a challenge or an opportunity to test myself in a new situation. Sometimes these assignments involved the technique of photographing ideas, which is something that has always fascinated me. When I met Salvador Dali in the early 1940s, I was able to expand in this area because of his own similar approach in his paintings. Our first set of pictures together started a friendship between us that resulted in a stream of unusual photographs”, Halsman used to say.

Among the famous friends and subjects of his portraits, Halsman counted Albert Einstein, of whom, Irene recalls, his father said he was the man who saved him twice and enabled him to come to America from Nazi-occupied France.

“My great interest in life has been people. A human being changes continuously throughout life. His thoughts and moods change, his expressions and even his features change. And here we come to the crucial problem of portraiture. If the likeness of a human being consists of an infinite number of different images, which one of these images should we try to capture? For me, the answer has always been, the image which reveals most completely both the exterior and the interior of the subject”, Philippe Halsman stated.

In the early 1950s, Halsman began asking his subjects to jump for his camera at the end of the session. These images have become an important part of his photographic legacy.

As curator Alessandra Mauro explains, “he created portraits of extraordinary power and psychological insight; he managed to make scientists, politicians and Hollywood stars jump in front of his lens”. The exhibition introduces us to Halsman’s universe “in a visual game between the photographer, the subject and the viewer, all together aiming at lifting the surface of the public mask and reaching something more intimate, more real”.

Indeed, as Halsman wrote “The end is another surface to be penetrated, this time by the sensitivity of the onlooker. For it is now up to him to decipher the elusive equation between the flat sheet of photographic paper and the depth of a human being”.

Rigour, creativity and a touch of strangeness to express The personalities of the characters. A playful (but also very serious) moment, because the precise instant provides a way of gaining insight into their psyche. Halsman identified it as a new psychological tool (as the true self becomes visible) which he called Jumpology.

“Philippe used to experiment: he created photomontages, reportages and advertisements in which his humour was expressed as well as his ability to create photographs as visual charades. The works by Halsman, as the title of one of his books says, are between sight and insight, proceeding from immediate intuitions, born of deep introspection and knowledge”, Domenico Piraina, director of the Palazzo Reale Milano, adds.

And then, when a particular kind of expressiveness was required, Irene Halsman explains, “images like of Marilyn Mao and Dali Mona Lisa were made with manual collages, using tiny scissors, to obtain the final photo”.

Philippe Halsman (1906-1979) was born in Riga, Latvia and began his photographic career in Paris, where he opened a portrait studio in Montparnasse, where he photographed artists and writers (including André Gide, Marc Chagall, Le Corbusier, André Malraux, using an innovative twin-lens reflex camera that he had designed himself. While in Paris, he worked for Vogue and Vu.

Halsman arrived in the United States in 1940, part of the great exodus of artists and intellectuals fleeing the Nazis, having obtained an emergency visa through the intervention of Albert Einstein.

In the early 1950s, David Seymour (“Chim”), one of the founders of Magnum, asked him to become a contributing member of the photo agency. He produced his fiftieth LIFE cover in 1951, the one dedicated to Gina Lollobrigida in 1951, too; the LIFE cover devoted to Marilyn Monroe was published in 1952 and his seventy-fifth LIFE cover dedicated to Audrey Hepburn in 1955.

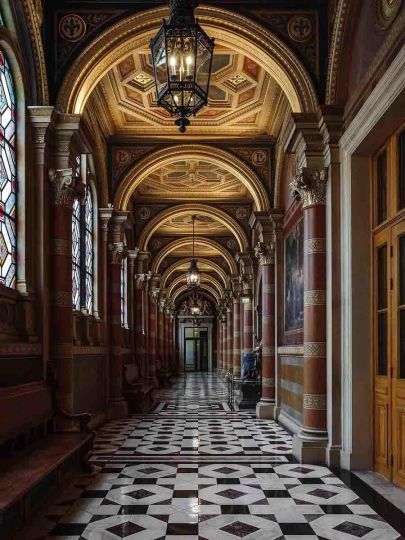

The exhibition, curated by Alessandra Mauro and supported by Comune di Milano – Cultura, is produced by Palazzo Reale, Civita Mostre e Musei and Contrasto with the support of BNL BNP Paribas and Leica Camera Italia.

The catalogue is published by Contrasto.

Philippe Halsman. Lampo di genio

Until September 1, 2024

Palazzo Reale

Piazza Duomo 12

20122 Milano

Italy

www.palazzorealemilano.it

www.civita.art/mostre/halsman