Rania Matar’s series “A Girl and Her Room,” touching portraits of teenage girls in their rooms, explores the adolescent experience and the role of Western influences in Lebanon and Palestine. Her new project “L’Enfant-Femme” focus’ on girls from the ages of eight to twelve. Both series are featured in the current exhibition, “The Middle East Revealed: A Female Perspective” at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, along with three other contemporary artists; Boushra Almutawakel of Yemen, Shadi Ghadirian of Iran and Reem Al Faisal of Saudi Arabia. In addition, Greenberg Gallery will show photographs from Syria by Margaret Bourke-White made in 1940 for LIFE Magazine.

I’ve been corresponding with Matar over the last year about her life, her work and her very personal journey growing up during the chaos of war.

Elizabeth Avedon: Where did you grow up?

Rania Matar: I was born and raised in Beirut Lebanon. I was 11 when the Lebanese Civil War broke out and I mention this as it was very much part of my growing up and the reason I eventually moved to the US in 1984.

My parents were originally Palestinian. They both came to Lebanon in 1948 when my mom was 9 and my dad 13. They met at the American University of Beirut and got married. I grew up like any Lebanese kid and it is not until much later, having lived in the US for 20 years, that I became interested in learning more about my Palestinian identity. I guess it was buried in there somewhere and I ended up including girls in the Palestinian refugee camps in all my work.

My mother died when I was three. When I was growing up, it was just my dad and me. He was the world to me, and me to him, I am sure. I don’t know if being without a mom influenced my interest in photographing women. A few of my friends are convinced it does. I honestly don’t know.

EA: Please elaborate on what it was like growing up during the Civil War.

RM: I have fond memories of my teenage years despite growing up during a messy war. I guess teens often don’t realize the danger that surrounds them. I had a relatively “normal” happy teenage life that depended however on the daily minute-by-minute situation in the country. If things were safe on a given day, then life was normal and the war quickly forgotten. The next day the fighting would start again and we would switch to war mode again. It is pretty incredible to me now, as an adult and living in the US, how resilient people and especially kids can be, and how we so easily molded our lives around the political situation and the war. I am glad I was kid and not a parent back then.

Despite the craziness around me, I had a pretty normal teenager’s life, in many ways similar to my own teenagers’ lives here in the US. In 1982, I studied architecture at the American University of Beirut. Then things got really bad and the war too close to home in too many ways, and I transferred to Cornell to finish my architecture studies in the US. I never went back to live in Lebanon. It was 1984.

EA: How has it changed since you grew up there?

RM: Looking back at it now when I visit, I realize how small my circle was and how confined to a very small area of Beirut my life had been. It was not safe to go too far and many places were off limit, so I got used to living in the very small safe area around me. I did not know the many fascinating places of Lebanon or meet the wonderful, warm, hospitable people I was so fortunate to discover and meet years later as a photographer (an American by then) when I started venturing outside the little circle my life had been limited to.

The country has changed in so many ways, but so did I and my perception of it. The Civil War is now over, daily life has a more regular rhythm and the country was rebuilt. There still is tension between different factions, religions and parties and the country still feels like it is always on the brink of something about to happen, but somehow peace is precariously maintained and life keeps going on.

However, having lived in the US since 1984, I was a different person. I was seeing with fresh eyes the things people were used to living with and had stopped noticing: a duality in just about everything one experiences in Lebanon: tradition and modernity, Christianity and Islam, Arab traditions next to a very Western cosmopolitan lifestyle, conservatism and decadence, destruction and reconstruction, wealth and poverty and the list goes on. The country being so small, this duality is always present.

Some of this duality is what makes Lebanon so diverse, special and interesting as a country with all those opposites intersecting intimately in people’s daily lives, but it also sadly creates problems in a country so fragile and so dependent on all the surrounding countries with all the factions and political divisions that come with that.

I also noticed that the wearing of hijab (the headscarf) had increased tremendously since I lived there. When I grew up in Lebanon, very few women wore the “hijab” or the veil. It was relatively rare to see a woman covering her head, let alone her face. I visit Lebanon regularly and saw over the recent years how Muslim women and girls have embraced religion and the veil for different reasons. In Lebanon women do not have to wear the veil, but wearing it is rapidly becoming a decision of choice among most Muslim women young and old, modern and traditional.

EA: How has your photography been influenced by where you grew up?

RM: My photography definitely was influenced by where I grew up. I became a serious photographer because of my background, but especially because of my dual identity as an American and a Lebanese.

My being from two worlds, and simultaneously belonging to two cultures, definitely has shaped my photography. In my earlier work, I felt that being originally from the Middle East and understanding so well the culture, I was able to photograph it with an understanding and an affection that is very personal to me. Living in the United States, I was able to convey my perception of my world over there to my world here, at a time when the news was very focused on a lot of negativity coming from the Middle East. What I knew was different. I wanted to make sure people who saw my work in the US, saw the Middle East I knew and was discovering further through my work. Photography led me to areas of Lebanon I had never been to before and introduced me to people I would have never met. I found that regardless of religion and political affiliation, people were just people. They were warm, welcoming, and resilient; they kept their dignity and their humanity despite all they had lived through. They trusted me and opened their doors to me with a humbling hospitality. I wanted to convey that through my work.

My being a woman and a mother definitely shaped my work as well. When I started photographing in the camps and in Southern Lebanon, and I started showing my work here, people always asked me “where are the men in your images?” In the beginning I was very upset at the fact that I could have ignored such a large part of the population! Then I went back to photograph and realized that I was interested in photographing women and children. I am a woman and a mother myself, and my instincts had led me in that direction. I had a “YES” moment, right then: I was photographing women and children in the Middle East. This was what defined my work and made it personal to me. Once I owned that fact, my work moved very consciously in that direction. It was liberating. And years later, I am still photographing girls and young women.

Eventually my work shifted to include my current life in the US, inspired and influenced by my own daughters. Even if I decided to do this work in the US, eventually the need of including girls from Lebanon and the Middle East became essential to me. This is how the work becomes personal to me. Those are the two cultures that formed who I am and who my own daughters are.

EA: What school were you attending when you were around the age of the girls in your photographs?

RM: I went to the same French school in Lebanon: the “College Protestant Francais,” from the age of three through eighteen! Even though it says “Protestant” it really wasn’t religious at all and had a varied body of the student population, kids from all religions. I grew up fully bilingual speaking French and Arabic. My father used to work with 3M and Merrill Lynch, so I was used to hearing English around me and it quickly became my third language back then.

EA: Can you describe how you felt at that age?

RM: I was a pretty happy easy-going normal kid, but I do remember being self-conscious at that age, like most girls. I had been a tomboy growing up with a dad only, so I had no woman role model in my home. My dad got remarried when I was 11 to a woman who had a daughter my age and I guess simultaneously nature was taking over as I was also transforming myself, my body was changing and I was understanding my womanhood and my sexuality. It was the first time I was turning into a little girl and also the first time since my mother had died that there were other women in my house.

It was also the time that the Civil War was starting in Lebanon and we spent a few months in France where I ended up going to school in Paris — things were really bad in Beirut at that time.

As I am writing this, I realize how much took place in my life at that age that I never realized…

EA: When did you begin taking photographs?

RM: I became a photographer in 2000 at the age of 35. I was originally trained and worked as an architect. In college, I took many art classes including painting, drawing and printing, but not photography. I always enjoyed photography, but did not formally start doing it seriously till 2000.

I took many workshops at the New England School of Photography and fell in love with the medium instantly. I loved being in the darkroom and seeing the images come to life. I was originally photographing my children mainly, while still working as an architect. In 2002, I was in Lebanon and went with a cousin of mine to a Palestinian refugee camp. I was shocked to see how people were living so close to where I had grown up and more shocked by the fact that I had no idea. I started photographing people in the camps, and fell in love with the ability to tell a story through photography, the ability to capture life and to freeze the beauty of those simply mundane moments of life into a permanent image.

Everything I had previously done and been, somehow felt like it led me to this. I never went back to architecture. I felt that my architectural training, my love for art and painting, my being as a woman and a mother, my growing up during the War in Lebanon, my current life in the US and my love of the Middle East, all combined to make this feel so right.

I eventually took more workshops at NESOP and then with the Maine Photographic Workshops in Oaxaca, Mexico with Constantine Manos and Stella Johnson in 2005. Costa became a mentor to me.

EA: What were your first subjects – what were you interested in photographing in the beginning?

RM: My children. And this is very important work for me. I think it defined how I photographed and approached everything in my photography moving forward. Photographing my kids taught me to appreciate the simple mundane fleeting moments of daily life and seeing the beauty in them. It taught me to photograph intimately and to always aim for this in my work. I think those early images, not only made me fall in love with photography, but also taught me to work on projects that are personal to me, that I love and am passionate about.

EA: When did you begin taking portraits for this project?

RM: I am very influenced in my work (or better to say inspired) by my own life and close surrounding. My work with girls, first with “A Girl and Her Room” and then with “L’Enfant-Femme” is very much inspired by my own daughters and watching them transform right before my eyes.

While “A Girl and Her Room” was inspired by my older daughter at 14, “L’Enfant-Femme” was inspired by my younger daughter who, at 12 was transforming before my eyes, alternating between being the little girl I knew, and a young woman I didn’t know yet. I also realized that simultaneously toward the later stages of working on “A Girl and Her Room,” I was starting to focus more on the details and the body language of the girl than on her space. “L’Enfant-Femme” ‘officially’ became what I was working on in 2011. I began in the US, in the Boston area where I live, but quickly decided to include girls from Lebanon. In the summer of 2011 I did just that.

EA: What was your intent when you first began?

RM: I guess anytime I start a project I go with a gut feeling and a vague idea and I let the project define itself as I begin. It has always seemed to work for me this way and I like the fact that the project ends up taking me somewhere I might not have been aware of. I knew I was fascinated with that age group. I saw my own daughter and how her demeanor was changing and how she was posing herself in life and for me. I knew I wanted to capture that very tender moment when a girl is starting to realize that she is on her way to becoming a woman. It is a very short time before the girls become teens and the attitude changes again.

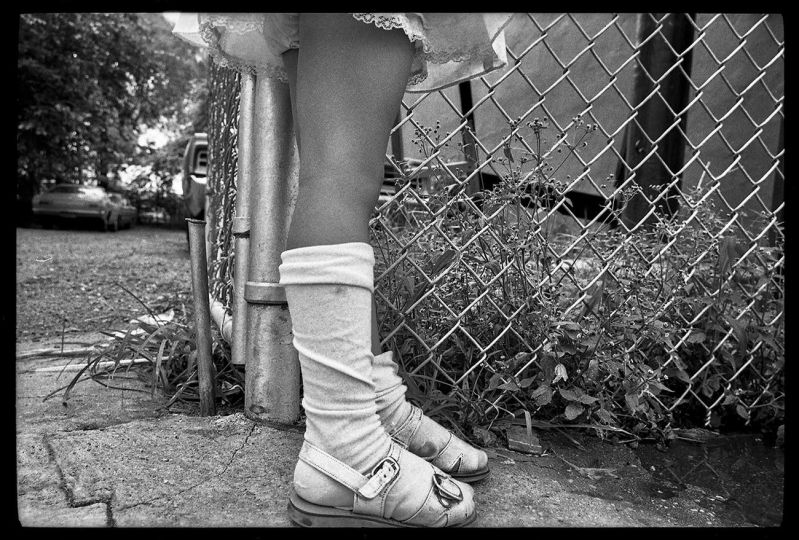

My intent in this project is to observe the details of posture, the body language, the expressions or the hands and sometimes feet. I asked the girls not to smile and I let them pose themselves.

From my statement:

These are portraits of young teens and pre-teens and how they interact with the camera. The only instruction I give the girls is not to smile and I allow them to fall into their poses. My aim is to portray the girl, when allowed to pose herself as she wishes in front of the camera. I try to capture alternatively the angst, the self-confidence or lack thereof, the body language, the sense of selfhood and the developing sense of sexuality and womanhood, that girls this age experience.

For some, even though they are not smiling, one can see their sense of selfhood and their almost sensual pleasure in being photographed and in engaging the camera, while others are almost defiant in the way only teens can be, and others still are more separate from the camera, show more angst, are more self-conscious or look away. These are all emotions girls this age alternatively experience as they become aware of whom they are, of their changing bodies, their beauty, and their womanhood, but also of the world around them and the standards of beauty and attitudes they think they need to emulate. However, these are also still young girls who fluctuate between being the child they still are and the young woman they are beginning to turn into. Are they (and we) meant to see themselves as little girls, as teenagers, or as young women?

EA: Has your original intent changed now that you’ve shot a large body of work?

RM: I don’t think my intent changed as much as the project defined itself and became clearer to me. I learned what to look for and how to interact with the girls better. Originally I hadn’t necessarily intended to have the girls look at the camera. It eventually became important to me. In my previous work this was not important. In this project I started looking for the reaction to the camera. The work is very much based on the interaction of the girl to the camera and the photographer. In my previous work, I often made myself disappear so I can capture the moment without any interference. In this work the interference was important. If a girl did not look and kept avoiding my gaze then it was important as well as it was her choice.

EA: How do you approach the girls or their parents to take their portraits?

RM: “For A Girl and Her Room” I most often approached the girls themselves. For “L’Enfant-Femme” I only approached parents. I explain that I am mother myself and that this work was inspired by my own daughter. I ask them if I can email them a small description and a sample of the work. I explain that the only purpose and usage of the work is art and that the images will only be used in the context of the project. It might help that I am small and don’t look very threatening to people, I guess.

The harder thing is for me to ask the parent to leave the daughter and me alone while we are working. This is a huge leap of faith on their part and I truly respect and appreciate that. The girls are undeniably very different when the mothers are present. It is very interesting to observe. The girls themselves know that and don’t want their moms present in the same space we are working.

Girls like to be photographed. They like the attention and they like having their own private photographers. I understand them on a very personal level; I know how to interact with them and the session ends up always being fun and cooperative. I have been trying to do something similar with boys and encountered much more resistance. I am still trying to work on the angle of what a project could be like for boys.

EXHIBITION

The Middle East Revealed: A Female Perspective

Rania Matar, Boushra Almutawakel, Shadi Ghadirian, and Reem Al Faisal

June 26 – August 30, 2014

Howard Greenberg Gallery

41 East 57th Street

New York City

USA

http://www.raniamatar.com

http://www.howardgreenberg.com

http://elizabethavedon.blogspot.com