Five years. This is how long Jill Freedman waits on and on to be rediscovered, and enjoy a few weeks of notoriety before slipping back into anonymity. Another five years before someone else come digging in the archives of this humanist documentary photographer and exhumes a few unpublished photos. This strange cycle has haunted her since the launch of her career which, in any case, has never been one.

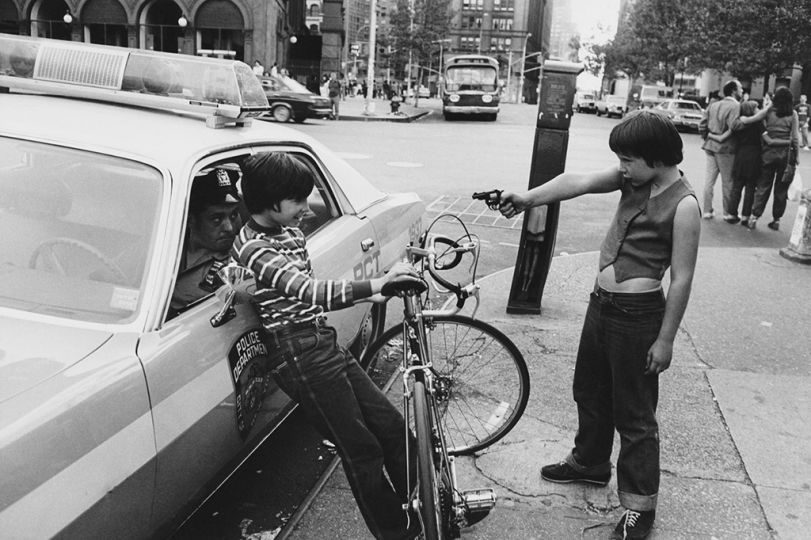

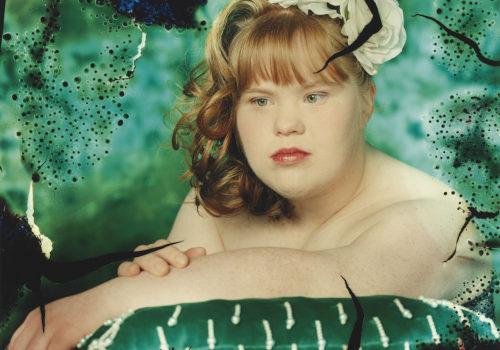

This time, it is the gallery owner Steven Kasher who devotes an exhibition to Freedman’s work. The title, Long Stories Short, puns on a set phrase and refers to her images which the photographer sees as long stories concisely told. We can speak here of a true rediscovery. This is kind of a new Jill Freedman: less gentle, less approachable, or less funny, but always asserting her reality, that is the reality of popular America and American life that alternates between bitterness and exhilaration. The selected photographs, intriguing and bordering on grim, emanate an uncommonly strange atmosphere: unguarded expressions, characters staring you in the face, uncanny scenes, the introduction of raw nudity, as well as the use of flash and the practice of nightly walks. The focus is on her city, New York, and all the complexity it contains.

But, unlike in her previous exhibitions or books, Jill Freedman’s work for the first time appears without a unifying theme, subject, or period. The exhibition was curated by the new gallery director Anaïs Feyeux. “I want to do away with the idea that Jill Freedman is a photographer only of subjects and causes,” Feyeux explains. “She has always treated photography more as a life companion than a way to make a living. I also want to show that Jill Freedman has a very ambivalent relationship with things. She may find the same event at once amusing, upsetting, and melancholy… In her relations with people, she may be very human as well as very sarcastic. There is often a duality to her images. The young mother clutching her child on a boat in Ireland (Smother Love, 1969) represents both a true act of love and a terribly violent, cannibalistic gesture. An exhibitionist alone in a Manhattan street (Gift Wrapped, 1983) is funny but also pitiful and completely lonely. In contrast to her books, or to stories that run on for dozens of pages, a single image often suffices to tell a story.”

Beyond the emotional dimension of her photographs, wich appears quite freely in Freedman’s work, there is also an as-yet unfathomed depth that is manifested here. “I wanted to foreground a formal aspect in Jill Freedman’s work,” continues Anaïs Feyeux. “This wasn’t, however, in view of defining a style; rather, I wanted to juxtapose in such a small space very different images, ranging from the more hazy scenes of the San Francisco photographs (1968) to the more frontal shots like the Speakers’ Corner in London (1969), or yet the more detail-focused, back-shot images such as Loose Change (1979). It is important to show that Jill Freedman used forms highly relevant to the time. For example, Smother Love (1969) brings to mind images produced some ten years later by other American or British photographers. In some of her photographs on the theme of the Holocaust, namely Holocaust Survivor (1982), she presents the survivors of the Shoah as assertive human beings, almost combatants, at a time when the only images we had were those made at the moment of the liberation of the concentration camps in which they appear as emaciated victims.”

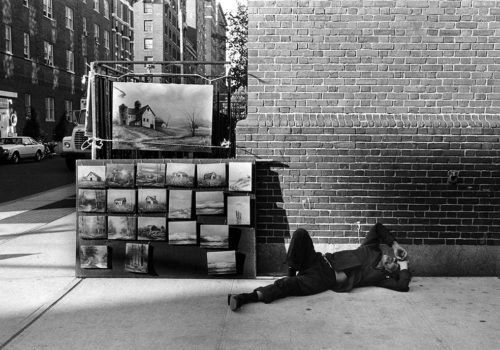

Recently, Agnès Sire, director of the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris, confided to Jill Freedman that she had uncovered a number of her prints in the Magnum archives. The photographer had entered briefly the famous agency in the mid-1970s, yet without ever being inducted as a full member. The photographer’s total independence, almost exhilaration, have combined to create a highly personal, untendentious body of work, more complex than it might seem, rich in multiple points of view, and yet possessing a raw quality. Jill Freedman does not treat photography as a job, and certainly not to climb the social ladder. Walking off the beaten path, she stays close to the facts of the world and feels at home in its harsh reality. These are the chief traits of her photography: it is generous and sensitive, it has a soul, a heart, and keeps the doors always open. But it’s never gullible. It turns its back on fortune. When she photographs artworks exhibited in the street, she’ll have a homeless person sleeping underneath.

EXHIBITION

Long Stories Short by Jill Freedman

September 17th – October 24th, 2015

Steven Kasher Gallery

515 W. 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

USA