Studio 54 was the world’s most famous and exalted discothèque. It opened in 1977 at 254 West 54th Street in New York City at a time when disco music was enjoying its frenetic peak. The establishment attracted the celebrities of the day and a carefully filtered mix of guests spreading their stardom. On the Studio 54 dance floor, everyone was a star. Hasse Persson spent hundreds of nights at Studio 54 between 1977 and 1980. His pictures have become legendary. Now, they are published in book form for the first time. Studio 54 can be seen as a return visit to an ultra permissive epoch and a social phenomenon. Interest in New York’s Studio 54 has today – 35 years after its peak – reached almost mythic proportions.

My Studio 54

On 26 April 1977, the Studio 54 discothèque opened its doors at 254 West 54th Street in New York City. Within months it was the most talked-about disco of its kind in the world and even though it existed in its original form for only about 1,000 nights, Studio 54 became one of the 20th century’s most famous entertainment venues.

Studio 54 was founded by two young entrepreneurs, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, who read the signs right and realized that disco music was to the 1970s what The Beatles were to the 1960s and Elvis Presley to the preceding decade. Rubell and Schrager paid 700,000 dollars to revamp a disused CBS television studio in Manhattan. Two of Broadway’s best known designers, Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz, turned the gigantic premises – 100 by 80 meters – into a disco world unlike anything seen before. On opening night, party promoter Carmen D’Alessio invited 5,000 of the biggest celebrities of the day, including Mick and Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, Jerry Hall, Margaux Hemingway and newlyweds Donald and Ivana Trump. Out on the street, chaos reigned! The line outside was a show in itself and became in time part of the disco’s attraction. Frank Sinatra, Cher and Warren Beatty could not get through the crowd, even though they had personalized invitations.

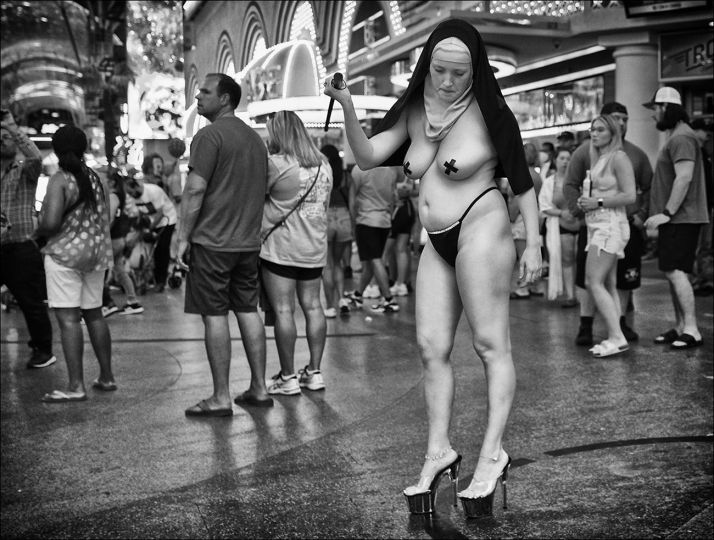

Studio 54 could swallow over 1,000 guests at a time. This meant that about 1,500 grateful people might be there on any one night while hundreds jostled in the queue outside, providing a panorama of scantily dressed and heavily made-up fans, all hopeful of catching Steve Rubell’s eye.

It used to be said that the queue system was a dictatorship while democracy blossomed on the dance floor inside. Steve Rubell, gifted with special social skills, had found a formula for maximum magic.

He wanted a “tossed salad” of guests – an eclectic mix. And he had a technique that he insisted his sidekick, Marc Benecke, slavishly adhere to when Steve was not at the door himself: Steve wanted the mix to include 20 percent gay guys and 5-10 percent lesbians and transvestites. The rest should include celebrities of any kind, Latin American millionaires and, ideally, visiting Eurotrash.

People with money and culture and with foreign idioms, spreading their stardom on the dance floor.

Steve Rubell treated Studio 54 like his own living room. He was aware of everything and everybody. There was no obvious security, outside or inside. Rubell used to perch on a lamppost or a step-ladder to select the thousand who would make it inside.

“You’re in! And you’re in! And you can get in another time if you shave that beard off or wear a different shirt.”

“No way!” was the usual call for those who didn’t make the grade.

Steve Rubell was brilliant at reading his public. He admits he once didn’t recognize the presidential kids, Caroline and John Kennedy, in line outside Studio 54. They should have just told him who they were, he says. On the other hand, Rubell was always happy to let in Harlem street kids. Their physicality, colors and dazzle were enlivening. Older people also had a quota, especially well-preserved, mature women with style.

Steve, sitting in a high chair outside his disco, mixed his “salad” with sober realism and tough honesty.

“I would never have let Steve Rubell into my disco.”

In his book Exposures (1979), Andy Warhol writes about his recurring nightmare that he was not let in to his favorite disco, since his friend Steve wasn’t always at the door. Warhol listed the five best ways to cut through the line at Studio 54:

1. Always go with Halston or in Halston.

2. Get there very early or very late.

3. Arrive in a limo or a helicopter.

4. Don’t wear anything polyester, not even your underwear.

5. Don’t mention my [Andy Warhol’s] name.

I photographed Andy Warhol lots of times at Studio 54. He did not like people to get too close. So he would always carry a camera or a tape recorder to shield himself. He was extremely hard to talk to. His usual answers were “fantastic”, “terrific” or just “wow”. The longest conversation I had with him was at a promotion for Absolut Vodka, the drink Warhol helped boost through his smart art. I asked him if he liked Absolut.

“I’ve never tasted it,” he said. “But I use it as a deodorant under my arms and between my legs.”

If it was a dictatorship outside Studio 54, the dance floor was a democracy.

You could see Michael Jackson do his moonwalk just for fun, or even get to dance with Bianca Jagger or Diana Ross. Everyone was a star, everyone who got in was a winner.

Music was obviously key to Studio 54’s success. New York’s best DJs, Nicky Siano and Richie Kaczor, spun the discs. Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” and “Hot Stuff”, Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive”, The Trammps’ “Disco Inferno” and the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” were always on the turntable. But the dance floor did not start cooking until the DJ put on Patti LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade: Voulez-vouz coucher avec moi (ce soir)?” or Musique’s erotic “In the Bush”. If the feelings were right, sex was only a balcony away or the nearest restroom cubicle. Everything was done with decorum and elegance, attracting only passing glances – or envious smiles. You had to keep on your toes or Steve’s radar would pick you up and you would be banned. It was probably lucky that the average age was decently high – between 30 and 40 – and that most patrons were successful professional people with reputations to protect, professionally and socially.

The times and the prevalent drug culture sanctioned this hedonistic halfway- house between heaven and hell. Somebody smart said Studio 54 existed after the Pill, before AIDS and while cocaine was still seen as a pick-me-up. The drug reference today seems vapid but a lot of people had been reading Sigmund Freud’s so-called cocaine papers. In his book Über Coca, published in 1884, Freud was full of praise for cocaine’s benefits, claiming it to be a far better drug than alcohol. And less harmful. When Freud also mentioned that patients who had been prescribed cocaine reported an increased sex drive, Studio 54 was easily convinced. “Push, Push, in the Bush” as Mustique put it.

In addition to the traditional Absolut and marijuana, Quaaludes were prized. Quaaludes are a sleeping narcotic and when mixed with alcohol also boost sex drive. The drug was made illegal by President Ronald Reagan in 1984. At the time annual production was 100 million pills, just in the United States.

The gay crowd liked poppers: alkyl nitrate, in use since 1857 as a treatment for angina. Poppers expand the blood vessels and provide an instant kick, lasting about a minute. With the disc jockey pumping out the Village People’s gay anthem “Y.M.C.A.” or “In The Navy”, it was poppers time.

Author Truman Capote, a Studio 54 regular and no stranger to alcohol or drugs, once said:

“This is the nightclub of the future. Completely democratic. Boys with boys, girls with girls. Black and white. Capitalists and Marxists, Chinese and others in a beautiful medley.”

A less known contributing factor was the staff, especially in the bars, and the busboys who collected glasses and dishes, emptied ashtrays and cleaned the toilets. They were skimpily dressed in clinging silk shorts, and gave off a sexual buzz. Part of the job was flirting. These were a male version of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy bunnies half a generation earlier.

But Studio 54’s huge success was also its downfall. In 1978, Steve Rubell was quoted in a New York paper as saying that his annual profit was seven million dollars, boasting that “only the mafia makes more money”. It was a slip of the tongue that provoked an unannounced visit by the IRS, the US tax authorities, and a police raid. Operating on a tip-off from a previous employee, the authorities located millions of dollars stuffed away in plastic bags in the disco. Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager were arrested, convicted of tax evasion and sentenced to three and a half years in jail.

After the court case, in an attempt to get his sentence cut, Steve Rubell accused Hamilton Jordan, the White House chief of staff under president Jimmy Carter, of sniffing cocaine in the VIP room in the disco’s basement. A grand jury met 19 times and 33 witnesses were called before a judge found Steve Rubell’s testimony to be unreliable.

Studio 54 closed down on 4 February 1980 with a gigantic wake called “The End of Modern-day Gomorrah”. Diana Ross, Richard Gere, Jack Nicholson and Reggie Jackson were among the guests. Steve Rubell had already packed a bag for prison and sang “My Way”, wearing a Frank Sinatra fedora. According to legend, Sylvester Stallone bought the very last round of drinks at Studio 54.

Steve Rubell died of an AIDS-related illness in 1989. Ian Schrager is currently successfully running his own chain of five-star hotels, including the Clift Hotel in San Francisco, the Paramount Hotel in New York and the Sanderson in London.

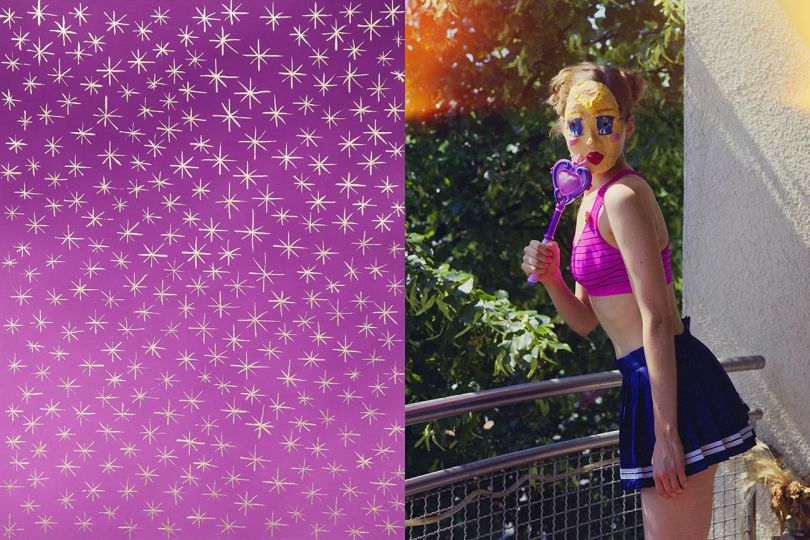

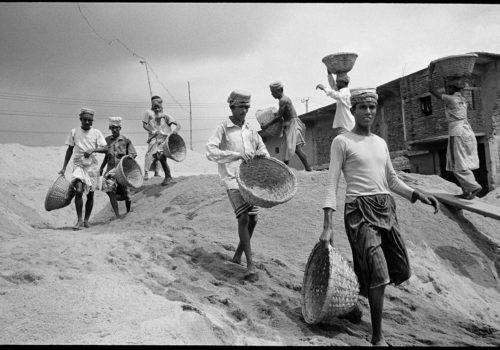

My Studio 54 pictures were created in the photographic tradition founded by the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The photographs have to have crystal-clear focus and be as technically flawless as any by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander or Diane Arbus. This meant that my pictures had to be taken on Kodak Plus-X or Tri-X and developed in D-76. The films were developed and contact copies made by Gar Lillard, whose laboratory in Carnegie Hall was also used by Irving Penn, Ernst Haas and Bert Stern among others. Most of my thousands of negatives from Studio 54 have never been printed before. After much experimenting, I finally found a way to capture the Studio 54 ambience on camera by using a flash to freeze the subject at the same time as I kept the shutter open for up to 30 seconds. This allowed me to catch movement on the dance floor, and the colored lights and other details that characterized disco culture.

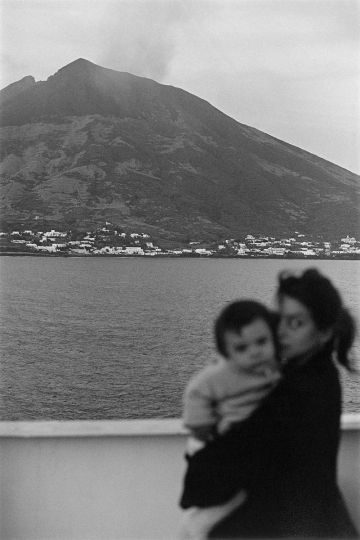

These pictures were taken more than 35 years ago and with time on my side I can claim that none of the other handful of photographers who were given generous access to Studio 54 ever discovered my technique, my way of photographically evoking the magic of the place with a unique concept. It is perhaps surprising that so few photographers and artists took disco culture seriously. My colleagues – documentary photographers Alex Webb, Gilles Peress and Mary Ellen Mark and others – were more interested in pictures of people on the bleeding edges of society. Another photographer, Garry Winogrand, focused on street aesthetics and street subjects. I was determined to avoid highlighting celebrities in my Studio 54 photographs, so as not to be compared to the paparazzi of the time like Ron Galella and others who were always present when there was some kind of disco “event”.

Most of the pictures are from my solo exhibition at Camera Obscura in Stockholm in 1979, at the time one of Europe’s best photo galleries. During the weeklong installation period, two well-known personalities visited daily: the legendary master photographer Christer Strömholm and the writer Ivar Lo-Johansson, himself fascinated by photography. Strömholm found my work in some ways paralleled his own studies of transvestites and transsexuals in Paris in the 1960s. Johansson was drawn to the socio-anthropological aspects of my pictures of America.

Fashion photographer Helmut Newton told me over dinner one evening that any photographer who claims not to be a voyeur is lying. I am happy to admit that I was at Studio 54 to observe, with the help of my camera, the human need for hedonism. I was there to take photos. I didn’t see Andy Warhol dancing either, nor Halston or Calvin Klein. They were there to re-charge their creative batteries. And to check out the kids’ clothes and perhaps put some of that into the next day’s fashion.

Another reason for my many nights at Studio 54 was that I was often beseeched by visiting Scandinavians to help them cut the queue at the disco. I recently saw a YouTube clip where [Sweden’s legendary] rock star and author, Ulf Lundell, told the audience at one of his shows that I had helped him cut through a 300-meter long line at Studio 54. I have no idea if the lines were actually that long, since I personally never had to wait to get in.

I’m pleased that I was able to help about a hundred rock stars, actors, photo models, ice hockey players, writers, publicists and one or two long-haired tennis players sneak into that exalted temple of pleasure. I wish that more people had had the experience of that fantastically seductive environment, so fascinating and so liberating. It is a comfort to know that the entire feel of Studio 54 has been preserved on 35-millimeter print film. Take my word for it!

Hasse Persson

BOOK

Studio 54

Hasse Persson

Edited by Max Ström

104 pages

22 x 29 cm

ISBN : 978-91-7126-325-4

http://maxstrom.se

http://hasseperssonphoto.com

http://www.amazon.com/Studio-54-Hasse-Persson/dp/9171263292