Le Musée Nicéphore Niépce presents the exhibition Paysage[s] Fresson[s].

With rare exceptions [Sudre, Brihat, Cordier], photography is a matter of shooting and then printing. Since Nicéphore Niépce, the tradition has been that photographers make their own prints, some in a specially designated space, adapted for the occasion, some in their bathroom, some in their kitchen. However, the industry quickly made this step invisible, mainly at the initiative of Kodak and its famous “You press the button, we do the rest”. Later, photographic agencies took care of the production of press prints when, for their part, photographer authors entrusted the printing to third parties. Sometimes because they considered that this operation was not that important. Sometimes because they didn’t have time. Sometimes because printers had managed to gain their trust.

In the latter case, photographers consider that exceptional artisans are those best able to show their approach, to reveal their intention better than they themselves would with this step which proves to be crucial. This often results in a certain exclusivity: some photographers only work with this printer and would not have their print made by any other.

The former Yvon Le Marlec, Claudine Sudre, Philippe Salaün or Roland Dufau [for color], the current Guillaume Geneste, Thomas Consanti, Diamantino… are all essential figures of the last fifty years for whom the print is an integral part of the work of the photographer.

Among this gallery of shooters, one name stands out, Fresson. And three first names: Pierre, Michel and JeanFrançois. A dynasty still active, in the person of Jean-François Fresson who works to carry out tests according to the family process, most often in color, developed by Pierre and Michel Fresson.

The Fressons are themselves the heirs of an almost bygone technical sector, that of pigment processes. Gustav Suchow revealed in 1832 that light acts on chromates; in 1852, William Henry Fox Talbot [1800-1877] reported that gelatin associated with potassium dichromate became insoluble after exposure to light; from 1855, Louis Alphonse Poitevin [1819-1882] exploited these properties to create the carbon process by incorporating carbon black into potassium dichromate.

This pigment process and its variations [carbon black can be replaced by other pigments] have the advantage of being better preserved than silver processes and experienced considerable commercial growth at the end of the 19th century.

These pigment processes offer photographers multiple creative possibilities, different from traditional silver processes. A number of photographers and producers of photographic papers contributed to the success of these different processes which notably won the support of photographers from the pictorialist movement at the turn of the 20th century.

The Fresson adventure began in this effervescent context around these pigment techniques when Théodore Henri Fresson [1865-1951] developed his own pigment process, which he presented to the Société Française de Photographie in 1899. His “charcoalsatin” process was a success of the family business until demand declined in the mid-20th century. From 1947, the activity of selling “charcoal” paper diminished and the workshop now produced prints for photographers, such as Laure Albin Guillot or Lucien Lorelle.

From 1950, one of Théodore Henri Fresson’s two children, Pierre [1904-1983], worked with the help of his own son Michel [1936-2020] to adapt the family process to color. When they settled in Savigny sur Orge in 1952, Pierre and Michel Fresson launched their color printing activity using the technique of their invention, the famous Fresson process, before being joined by JeanFrançois in 1978.

Obtained after decomposition of an original into colors through four filters [cyan, yellow, magenta and black], then exposure to light for all four successive colors before a bath of lukewarm water and slightly abrasive sawdust, the final test is the result of a perfectly mastered complex technique and unique know-how, within a workshop whose thermohygrometric conditions are perfectly known by the operators.

Producing a Fresson print is a complex process, which calls as much on technique [the application of successive layers on the paper is the result of a special machine manufactured by the Fressons themselves in 1952 and still used today] as the printer’s eye and his control of his environment. During the process, accidents are numerous, notably when the paper which is too heavy tears coming out of one of the baths, causing a sudden tension of discouragement in the shoulders of the printer [! ]: everything has to be started again. Two to five days of work are not too long to obtain these photographs in recognizable colors: soft, satiny, warm, sensual, slightly blurred, almost grainy despite the smooth paper and often in small formats [most commonly 21 x 27 cm].

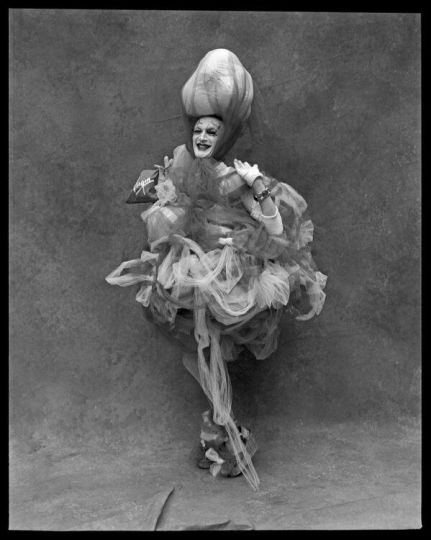

Some people don’t like this aesthetic. That have the art of transforming mediocre shots into “good photographs”: the singular atmosphere induced by the process are the charm of the print. But this assertion is true for all printers, it is in this way that we recognize an exceptional printer, capable of extracting the best from a negative. The Fresson process is also the last occurrence of an outdated artistic movement, pictorialism, where technique and aesthetics come into contradiction with amateur practice and vernacular photography.

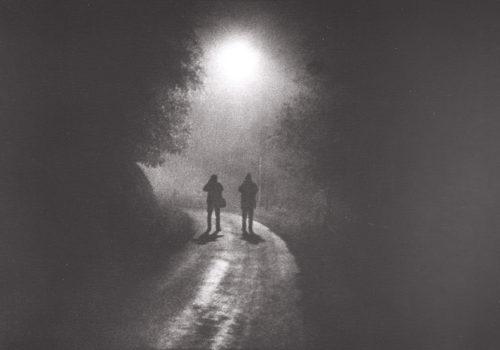

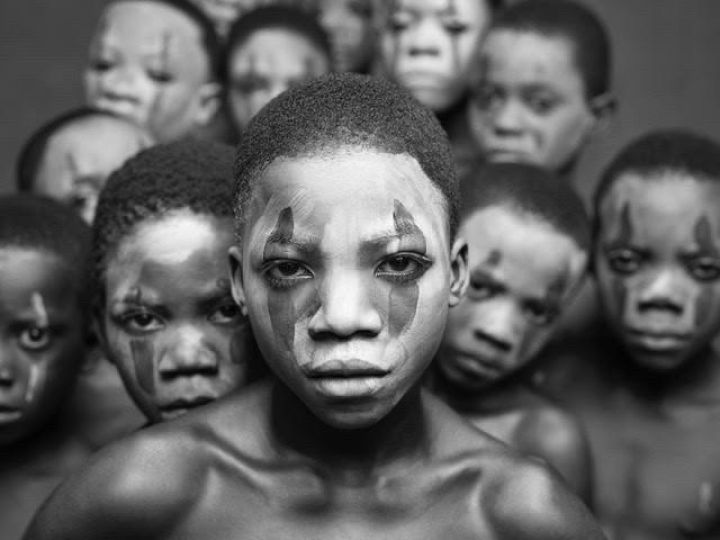

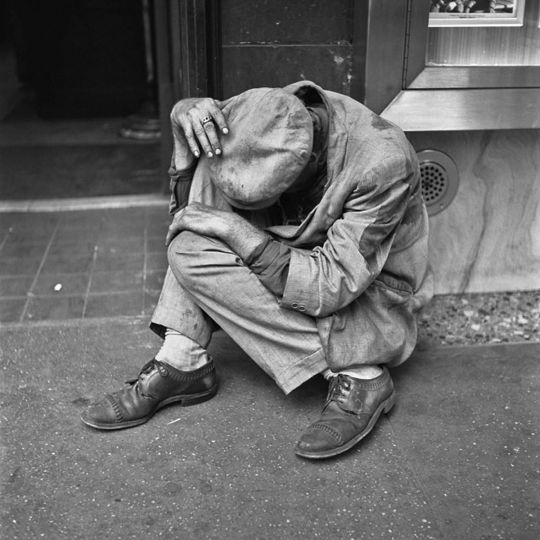

Others, such as Bernard Plossu and his friends, swear by the Fresson process. Certainly, the Fressons excel at magnifying an “image”, at adding confusion to confusion, accentuating the qualities of a “perfect” framing, at adding [creating] meaning to an apparently banal photograph.

Bernard Plossu was able to identify in the Fressons knows how to enhance his photographs. Far from being paintings, his photographs of elements of reality the most anecdotal, always perfectly framed, find more meaning thanks to the Fresson process, giving the viewer the impression that he feels what the photographer felt at the time of the shot. Bernard Plossu’s photographs taken by the Fressons become impressionist compositions where the muted color invites examination and introspection, the choice of small formats reinforcing this immersion. It is believed that the Fresson process was invented for Plossu, as his photographs resonate with the process.

The name Plossu has been inseparable from the name of his printing workshop, since 1967 when Plossu discovered the process. And Bernard Plossu became the best agent for the famous Savigny sur Orge workshop. Moreover, since the beginning of the 1970’s, Plossu has documented the life of the workshop and goes there regularly to photograph the dynasty at work.

If the Fresson process and Plossu’s photographs were able to find and magnify each other, Bernard Plossu is not alone. Over the years, he has surrounded himself with a “family”, where walking, strolling, photography and the Fresson process are the common denominators. Around Bernard Plossu, the exhibition brings together some members of this vast family: Jean-Claude Couval, Douglas Keats, Philippe Laplace, Laure Vasconi and Daniel Zolinsky.

Jean-Claude Couval roams the Vosges to find traces of the First World War, while Douglas Keats travels through Italy and Mexico. Daniel Zolinsky does useful work by listing, like the Heliographic Mission, the ancestral churches of New Mexico, vestiges of the evangelization of the natives by the Portuguese and Spanish colonists of the 16th century, while playing with the particularities of the Fresson process in declining at several hour intervals according to the same point of view the church of Ranchos de Taos. A fan of the charcoal process, Philippe Laplace offers pictorialist compositions of the paths and trails he crosses in France. While Laure Vasconi leads a singular and solitary stroll through old film studios in the United States, India or Italy, in search of ghosts, the Fresson process adding mystery to mystery, the photographer creating new landscapes within these fictitious landscapes.

At the heart of the exhibition, as a tribute to the different generations of Fresson and to the process, two color series by Bernard Plossu, the fruit of American stays in the early 1980s. One was the last series printed by Michel Fresson when the second was the first printed by Jean-François Fresson. The Fresson spirit is there but the differences demonstrate if there was still a need for it that the process is not everything: it is the eye and the hand of the printer that makes the print unique.

Sylvain Besson

Exhibition curators:

Sylvain Besson, Nicéphore Niépce museum

Bernard Plossu

Paysage[s] Fresson[s]

February 17 – May 19, 2024

inauguration Friday February 16 – 6 p.m.

Musée Nicéphore Niépce

28 quai des messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

03 85 48 41 98

www.museeniepce.com

www.open-museeniepce.com

www.archivesniepce.com