It’s an exciting moment for artist Mona Kuhn. She has two new series coming out at the same time. “Acido Dorado” opened last week at Flowers Gallery, Kingsland Road in London. And this week during AIPAD in NY, two galleries will be previewing her upcoming series titled “Private”, Jackson Fine Art and M+B. Steidl is printing the accompanying book in May, to come out in early Fall as part of Paris Photo.

I spoke with Mona about her new work and her experiences traveling in our western deserts.

Elizabeth Avedon: Tell me about “Private.” How is it different from your other new series?

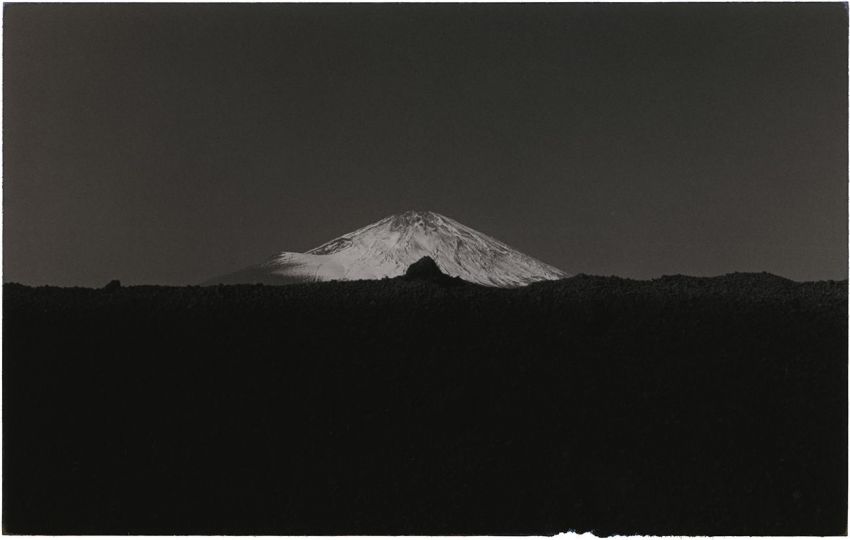

Mona Kuhn: “Private” is quite apart from “Acido Dorado”. It is a calm and introspective series, a lot more enigmatic. It is a meditative collection of images I took over a period of 2-years. I entered the heart of the American desert, travelling through the Mojave and Arizona regions, entering for the first time the remote parts of a Navajo reservation, areas close to James Turrel’s Roden Crater. “Private” is a personal journey, weaving together the desert beauty with its brutal sense of mortality, understanding mysticism and our place in it.

I usually start a new series with colors. I knew I wanted a little bit of that golden sand skin tonality. I wanted black as it has a certain sense of mortality. You are constantly testing your endurance in the desert, the limits of how long you can stay out there or how debilitating it is to be at 100 and some degrees. Your system really slows down and you can’t think straight. So the whole series is about our vulnerability in that environment as a metaphor to life.

At the time I was reading T. S. Eliot “The Waste Land.” There are no direct parallels, but I noticed a certain essence of his poem in the work, like a perfume that stays in the air after someone left.

I wanted to approach what is truly strange, beautiful and disorienting about the desert. Aside from vast landscapes and intimate nudes, for the first time I also photographed a few desert animals as metaphors. I was intrigued by their mysticism, like desert shamans, they have an instinct of their own. They know well their place and function in that vast space. Like the California pale moths that fly into the light. Or a black widow tattooed on a woman’s hand. I photographed a majestic black condor, then I photographed a Nephila’s golden spider web. Animals seem to understand nature’s balance and survive better than humans in the desert.

I met a lot of people who moved to the desert because they want to escape or get “off the grid”. But the desert is not for the weak of the heart. It offers an alluring American sense of freedom, but its harsh reality does not cease to remind us of our own limitations. It is shocking to face one’s own mortality. Lee Friedlander once said: “The desert is a wonderful, awful, seductive, alluring stage on which to be acting out the photography game.”

One of the homes I stayed in was built on top of this slanted rock formation. Underneath that slanted rock, there was a large shaded open area, like the shape of a mouth half open. A perfect habitat for rattlesnakes. This guy had dozens of stretched rattlesnake skins stapled on plywood board to dry out, all over the place. Hundreds of snakes live right under his rock foundation. I arrived at places and entered homes I could have never imagined before. But at the same time, being who I am, I wasn’t going to photograph the desert like “Breaking Bad.” I wanted to photograph the desert with a certain human element to relate to the beauty and the harshness. So there is a lot more landscape in this series than most.

The light is incredibly sharp; it contracts the pupils into tiny dots, making views of crystal clarity in which light and land are one. At times, I would photograph just the light by itself, its abstractions, bright sunlight and the graphic dark shadows – it had a powerful and minimal feel to it.

I photographed some people along the way, at times in their homes. Most homes I have been inside had their curtains closed. People get tired of the heat, you start feeling the weight of light, it becomes heavy. You go into people’s homes and all shades are down. Some of the desert people I met prefer to live in darkness.

You can easily loose the sense of scale in the desert.

In 1930’s, Georgia O’Keefe would often refer to what she called the “Faraway Nearby”. I photographed what seemed to have a force and scale of its own, that being macro or micro.

One of these beautiful places was Grand Falls in a Navajo Reserve in Arizona. It is a larger than life multilayered waterfall system. But the water is not clear; the water carries this monochromatic sand-like tonalities with it. It looks like a waterfall of skin tones. There, water and skin become one.

On the opposite scale, I found a little spring flower that was so frail. It’s very delicate image shot from above. T.S. Elliot would say that Spring season lasts only one day in the desert. The Spring flower rises in the morning and dies at night.

Along a similar scale curiously I shot from the computer screen an image of California City, a planned but unrealized urban development. The roads marked out in the dust for a civilization that never really came, seen from a camera orbiting miles above the desert. Like ruins in reverse.

EA: How did you come up with the title of the series?

MK: I spent a few weeks with Paul Ruscha in Winslow Arizona. He invited me to stay in his El Gran Garage, a large and mostly empty building in Winslow. It used to be the Greyhound Bus wash station before the highway was built and Route 66 lost its appeal, when the station was sold. The city receives a few visitors, but it is mostly a marginalized place. I spend many days just walking around, guided by curiosity. One of those days, I entered this store owned by a gentleman whose wife died twenty years ago. He wanted to sell the store and move, but was never able to leave. He still had his things packed in boxes 20 years later. The front of the store was open to the public and then in the back he had a sliding glass door and a curtain, separating the store from his personal area where he has his bed. The word “private” had been placed on that glass door a long time ago. You could see how the brightness of the sun had eaten away the type, devoured the lines that essentially hold it together.

Later on when we were editing the book, Steidl and I looked at that image and he said, “I think this needs to be the cover. It feels to me that you are looking for clues in the American landscape for the certain human condition, and that is indeed part of a private conversation. The reversed word is perfect, because you belong in that side. You are interpreting it from within.”

ACIDO DORADO at FLOWERS, LONDON

EA: “Acido Dorado” just opened at Flowers Gallery in London. How is that series different from “Private”?

MK: “Acido Dorado” is the most abstract work I’ve ever done. I’d been working on my other series “Private” for maybe two years and then suddenly this series “Acido Dorado” just happened. You know how artists say they just had a lightening bolt come and hit them? It was like that.

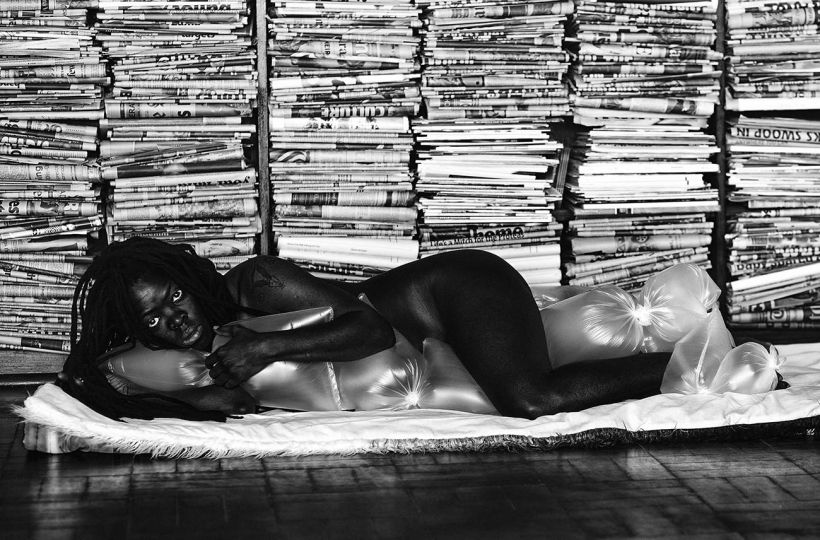

A Dutch model I’ve been working with for ten years just happened to be in the U.S. and the structure of mostly glass and mirrors that is not always available, became available. When we got to the Joshua Tree area, we were equally inspired by the light, by the nature, by the desert. It’s a very raw landscape. It’s not manicured at all, just raw sand. The house had huge glass doors. Everything was glass, reflections and mirrors where you have the feeling you are both inside and out because there were no walls. I was able to use the glass as a surface to my work and see how the golden desert light creates shapes over a period of time each day. Then over a period of a few weeks, I was able to observe how the incredible desert light moves around that space, how the figure fits in the space at different times and then again moving away from just photographing a nude, to photographing an abstraction of the nude.

There’s a lot of fragmentation. It was the nude as it was reflected on the glass and broken up into pieces through the tiled mirror or the landscapes juxtaposed in the reflection of the glass. It was shot during the summertime, so it will look hot; at times it feels like a mirage. There are certain distortions and a sense of disorientation in it.

In “Acido Dorado” my visual narrative shifted from the nude expressed in the physical body to the abstracted expressions of the body. The desert light and glass architecture presented the perfect platform for a certain mix of California hedonism and surreal desert hallucination.

There is a lot of solitude in the desert; so working with one person was a natural consequence of being submerged in that emotion. You travel miles before seeing someone else. The desert gives you a sense of freedom and loneliness at once. Also, I wanted to embrace the idea of repetition. Once I narrowed to one model, it became less about portraiture, and more of a conceptual exploration.

Elizabeth Avedon and Mona Kuhn

EXHIBITIONS

Mona Kuhn: Acido Dorado

4 April – 10 May 2014

Flowers Gallery

82 Kings Road

London, England

Mona Kuhn: PRIVATE

April 9-13

AIPAD

Jackson Fine Art – Booth #102 and

M+B Gallery – Booth #423

Park Avenue Armory

643 Park Avenue (67th St.)

New York, NY 10065

USA

Links

http://www.monakuhn.com

http://www.flowersgallery.com

http://www.jacksonfineart.com

http://www.mbart.com