Santu Mofokeng. Una solitudine silenziosa. Fotografie 1982 – 2011

Modena: a glance to the 12th century romanic cathedral and to the stunning reliefs by Wiligelmo (that look so much like a reportage), then you can focus on photography which is a star attraction in town since the beginning of March. In fact, a series of events have been held on Sunday, including the announcement of the winner of the 1st edition of the International Photography Prize: Santu Mofokeng, from South Africa, to whom the exhibit “A Silent Solitude. Photographs 1982-2011” at the Foro Boario (March 6th-May 8th 2016) has been dedicated.

The Prize, promoted trough the collaboration between Fondazione Fotografia Modena and Sky Arte HD, in partnership with UniCredit, is a biennial award (which includes a personal exhibition, a tv special and a 70 thousand euros cash prize) presented to a living photographer who has made a vital contribution to contemporary photography. The Prize, this year on the theme of identity, has been awarded by an international jury composed of Christine Frisinghelli (founder of Camera Austria), Shinji Kohmoto (founder of Parasophia Festival, Kyoto), Simon Njami (co-founder of Revue Noire), Thyago Nogueira (Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo) and Filippo Maggia (Director of Fondazione Fotografia Modena).

“The discussion the jury had while deciding on the winning photographer was exciting”, Filippo Maggia says. “There were well-known artists such as Rineke Dijkstra and Yasumasa Morimura and photographers who spent their lives championing important causes like Claudia Andujar, Zanele Muholi and Jim Goldberg. Then there was Santu Mokofeng, “an artist who has made his reserve a way of life. He does not belong to any system and this freedom gave him a creativity which is totally open-ended, and revolves around the theme of establishing an identity through a variety of subjects and the ability to approach them clear-sightedly”, Maggia adds.

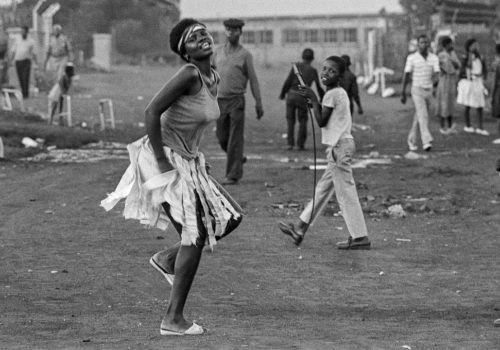

During a lifelong work, Mofokeng has been documenting the reality of his country, without rhetoric or pity, but with a sense of ethics and an almost scientific attention for research, with an empathy that closely links the photographer and his subjects.

“Being a photographer at the time was not an unmotivated act. A moral and sometimes physical war was fought and South Africa was its arena. Photography could not afford to be an artistic abstraction. It was a political and intellectual commitment. But it remained, in spite of everything, a form of writing and that is how Mofokeng approached it. Not like his country’s freedom fighters who denounced the iniquity of the ideology behind apartheid, but as the very special witness of a story which, until then, had been suppressed”, Simon Njami, curator of the exhibit and the catalogue (published by Skira), says.

Mofokeng had a multifaceted work experience. As a street photographer, he went where the clients asked him (to weddings and ceremonies), and his idea about that period was that the client was lord and master. It was he who decided on the “quality” of the images because it was he who paid. Though photography brought him popularity in the townships, he didn’t yet consider it a possible profession, a “real” job until he became a darkroom assistant for a newspaper. But there was no hope of advancement for a black. In 1985 he joined the Afrapix collective, which was a turning point in his career, when he met another kind of photography. Thanks to the collective he bought a camera and worked with an alternative newspaper, The New Nation. There he covered the simmering discontent in the townships.

“He felt drawn towards the people he met while he was covering a story, subjects that wouldn’t make the news in a paper. He also discovered that being a photojournalist, you were regarded with suspicion and that permanent tension was not what Santu Mofokeng was looking for. To him, a certain distance, a certain slowness were essential. He abandoned the struggle of the freedom fighters: if photography were a weapon, he didn’t feel at ease with the way the press used it and devoted himself to the documentary form, which seemed to have a rhythm more suited to his aspirations”, Njami explains.

So Mofokeng started his new way of photographing, with exhibits devoted to townships, in order to show in the best possible way the reality, serving a cause and correcting mistakes of the “traditional” image of the township people.

“I began to understand the messages I was trying to send, however different from others that came before, would always be over-shadowed by the assumptions about South Africa that viewers bring with them. The other thing that became clear to me was that in my pursuit of the art I was not paying enough attention to the narratives and aspirations of the people I was photographing. I had simply graduated into being a professional photographer without first pondering the meaning of this switch. I had not thought about my own responsibility in the continuing, contentious struggle over the representation of my country’s history” Santu Mofokeng says.

Typical of this new awareness is his research into photographs of black South African families taken at the beginning of the 20th century. The Black Photo Album: 1890–1950 focuses on a collection of images of well-to-do families of the once South African middle class wiped out by apartheid, with the aim of reaffirming their existence. “This is how I began to explore the politics of representation (and how) I became aware of urban family portraits that were made at the beginning of the last century. These images were slowly disintegrating in plastic bags, tin boxes on top of cupboards in the townships. And because they lie outside the consciousness of the education system, including the museums, galleries and libraries in this country, I found them enigmatic. … My quest for an explanation for this omission in my history education made me appreciate the magnitude of the crime of apartheid”, the author adds.

“With this project Mofokeng went back to actively opposing the established regime. But this time he realized that meaning did not reside solely in the actual things that were shown. It is possible to act on people’s minds simply by evoking things. Something that the viewer must finish supplying through his own references and his own sensibility”, Njami says.

EXHIBITION

Santu Mofokeng. Una solitudine silenziosa. Fotografie 1982 – 2011

From March 6th to May 8th, 2016

Foro Boario

Via Bono da Nonantola 2

41121 Modena

Italy

+39 059 224418

http://www.fondazionefotografia.org