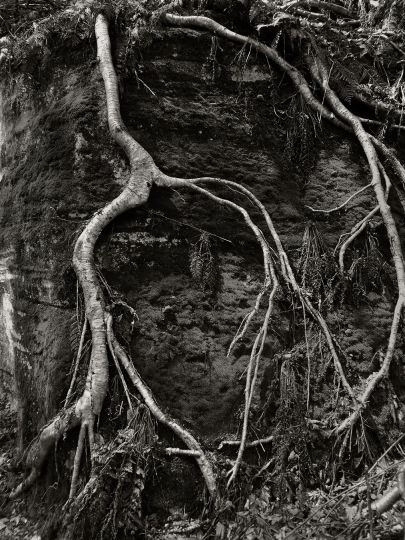

Colstrip, Montana (Taverner Press/D.A.P.)

by David T. Hanson

Colstrip, Montana: Population today: 2,500.

Once the tribal land of the Crow, Colstrip was known as the place “Where the Enemy Camps” and “Where the Colts Died.” The Native Americans’ notion of the Seventh Generation (specifically formulated in The Great Law of the Iroquois) stated that all actions and decisions should be guided by the principle of their impact on the seventh generation into the future. This way of life stands in sharp contrast to the industrialists who have permanently transformed the American landscape.

Founded in 1924 by the Northern Pacific Railway, Colstrip is now the site of one of the largest coal strip-mines in North America. It is also home to the second biggest coal-fired power plant west of the Mississippi, which has been named one of “American’s Biggest Polluters” by Environment America in a 2009 report.

Colstrip is a toxic citadel, hidden from view by virtue of Montana’s sparsely populated lands. Out of sight, out of mind could best describe how we deal with our impact on the environment. Without photographers, writers, and journalists to venture into these forgotten lands, we might never understand the devastation we wreak. In what seems to be a movement called progress, what we are really doing is destroying the earth.

Colstrip, Montana (Taverner Press/D.A.P.) by David T. Hanson bears witness to the systematic destruction of the American continent in our unrelenting quest for fossil fuel energy. Exhibited by John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1986, these photographs are part of Hanson’s critical examination of the contemporary American landscape as it reflects our culture and how we live now.

In the afterward, Rick Bass writes, “There is enough coal in Montana to end the world—to extinguish it in one long rogue flame.” There’s enough coal to keep poisoning the planet until we, as Americans, understand that our business practices, consumer habits, and lifestyle choices are the reason for this brutal devastation.

Coal is one of the dirtiest forms of energy, with high concentrations of toxins and hazardous waste products. The coal industry is heavily subsidized by the government and protected from environmental regulation, making it appear to cost just a few cents per kilowatt hour—but this conceals the true costs of coal. As forests and lakes are destroyed by acid rain, thousands of Americans die every year from the ozone particulates discharged by coal-burning plants, while many more suffer from asthma attacks.

The Colstrip plant burns 1,200 tons of coal each hour, or roughly an acre of land every day and a half. For a power plant that consumes enormous amounts of water to fuel and cool its steam turbines and to flush out its waste products, Colstrip is located in a dry part of Montana where the barely-adequate water supply is critical for farming and ranching. Water is a precious resource, and Colstrip has drained and contaminated the aquifers in the area. New water is piped from the Yellowstone River, 30 miles away, to run the plant, which consumes 22,000 gallons every minute. The water is also used in an extensive system of evaporation ponds designed to dispose of the waste produced by the plant. The company’s policy of “acceptable leakage” from the waste ponds allows for the discharge of thousands of gallons of toxic wastewater to pollute the earth and water table. Even farmers and ranchers far from the mine have had problems with their wells being poisoned or drying up. All of the town’s wells were severely contaminated and have been closed.

Add to this the emissions from the factory’s stacks, including more than 400 pounds of sulfur dioxide every hour, resulting in sulfuric acid falling onto the landscape of parts of Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota. The mining and burning of coal also emits nitrous oxides, carbon dioxide, and methane, all of which contribute to global warming on a large scale.

Since the mines first opened in 1924, over 550 million tons of coal have been dug up. Enough earth has been moved to fill both the Erie and Panama canals five times over. Although required by law to reclaim the mined land, the Colstrip mining company has actually reclaimed only 2% of the land that has been mined so far. With 120 billion tons of coal reserves remaining in Montana (one-fourth of the total reserves in the U.S.), there is enough coal to end the world in one long flame—or to keep Colstrip in business for a long time to come. Renowned climate scientist James Hansen refers to the coal trains that leave Colstrip every day (carrying coal to Midwestern power plants) as “death trains”. By Hansen’s reckoning, Colstrip will cause the extinction of 400 species.

Although created in the early 1980s, Hanson’s photographs of Colstrip are perhaps even more relevant today, due to our growing concerns about energy production, environmental degradation, and climate change. In the words of poet Wendell Berry, Hanson “has given us the topography of our open wounds.”

The interaction of humans and their technology with nature is a subject that has been of particular interest to American artists and is inseparable from our shared heritage in the taming of the wilderness. The historian Leo Marx referred to this theme as “the machine in the garden.” In Colstrip, Montana, the process is seen at its endpoint. The machine has ravaged, even consumed, the garden. The photographs reveal an entire pattern of terrain transformed by men to serve their needs. Colstrip becomes both arena and metaphor for the destructive aspects of the American culture, a mirror of our use, misuse, and abuse of power.

Hanson’s late twentieth-century landscapes begin to trace the geography of the mental landscape of our time. Like the ancient megaliths of Stonehenge and the lines of Nazca, the Colstrip site may be seen as a monument to the dominant myths and obsessions of our culture. Indeed, it seems likely that the most enduring monuments that Western civilization will leave behind for future generations will not be Stonehenge, the Pyramids of Giza or the cathedral of Chartres, but rather the hazardous remains of our industry and technology. Instead of the sacred sites of Ryoangi or Borobudur, we will leave to future generations vast gardens of ashes and poisons.

Hanson’s photographs reveal our distorted notions of progress as we have realized the logical conclusion of our Manifest Destiny and have transformed the American continent from wilderness to pastoral landscape to industrial site and now to wasteland. Colstrip has become a landscape of failed desire. Hanson’s pictures are tragic reflections of a brutally despoiled environment.

On the other side of the globe lies another circle of hell. The Agbogbloshie dump, located on the outskirts of Ghana’s capital, Accra, is a wetland turned wasteland, a slum and a workplace populated by thousands of men and boys who refer to this area as Sodom and Gomorrah. This is a slum of the twenty-first century, a place that Western countries would never allow within their borders, a place that could only exist among disenfranchised—in the rice fields of Guiya, China; behind the electronics markets of Lagos, Nigeria; in the back alleys of Karachi, Delhi, and Hanoi. It is the place where pits are dug and fires burn, and in those fires, our Information Age truly leaves its mark.

The United Nations Environment Program estimates that we now produce 50 million metric tons of e-waste per year, and 6,500 tons will arrive each month at the Port of Tema, where it then finds its way on to Agbogbloshie.

As Jim Puckett writes in the after word of Pieter Hugo’s new book of photographs documenting this ghastly landscape, Permanent Error (Prestel), “The equipment has the capacity to seriously harm human health and the environment from toxic ingredients that are persistent and in the case of toxic metals—immortal… The mountain ranges of e-waste arising on every continent represent an unforeseen toxic chemical crisis. Electronics manufacturers know that the only way they can maintain such staggering profits while address these troublesome waste mountains is to be seen as actively promoting recycling. Instead of seeking to produce longer-lived, upgradeable products, the pattern that is promoted is to buy, recycle, buy and recycle in rapid succession.”

But this recycling is so far from green it is the color of sludge. The workers in these poisoned pits make their living first by hauling then smashing, gutting, and burning the televisions and computers to recover copper, steel, and aluminum. The only thing green in this equation is the money being made by electronics manufacturers, whose sales are booming—despite the recession—for computer games, printers, electronic toys, MP3 players, digital cameras, GPS devices, camcorders, tablet readers, computers, and televisions.

Presently, the United States, New Zealand, Australia, Israel, Japan, and South Korea refuse to honor the Basel Ban Agreement, which was created in 1995 to ban the export of all forms of hazardous wastes for any reason. Of these countries, only the US refused to ratify the original 1989 United Nations treaty known as the Basel Convention, which created a full an on the export of toxic wastes for any reason from developed to developing countries.

The result of this failure is the creation of places like Agbogbloshie, where the unrelenting waves of the Information Age crash upon the shores like tidal waves. Pieter Hugo’s photographs show us the price of progress, an unquantifiable desecration of the earth and its inhabitants. This kind of inhumanity reaches a level on unconscionable ignorance that Hugo’s photographs brutally address. Baring witness to a new kind of inferno that is in its nascent stage, Hugo’s photographs stand as a testament against our complacent assumptions. “Recycling” is the chipper chatter of marketers leading the masquerade.

Colstrip, Montana and Permanent Error stand in dark warning and reveal the reality of our brutally consumerist lifestyle. We share this responsibility, just as we share this earth. You and me, your friends and family, all of us are the reason Agbogbloshie and Colstrip exist. That Hanson and Hugo have the wherewithal to show us the truth? We should be so lucky as to look and listen before it gets worse.