The portrait has become the icon of our times. Where we once venerated gods and saints, we now elevate ourselves to the object worthy of beholding, worthy of veneration—by ourselves, our loved ones, or by perfect strangers. The portrait is a means of recording that one moment in time as a universal constant; this is us now and forever more, this is who we are and how we see the world. And as we see, so we are seen. And as we believe, so we become.

The portrait was originally an invention of painting and sculpture, a means of recording greatness to sway the populace. Kings and queens and lesser nobles had likenesses produced as a means of asserting their power. For the image speaks in every language and can be understood by all, no matter when we live, what we perceive through our eyes is a mirror of the world.

When photography replaced painting as the tool of recording life, painting had to redefine itself. But photography was immediately taken as a form of truth, as a means of both art and reportage at the same time. It is a construction, in as much as all objects exist in our mind first. But it is also the reconstruction of memory as mediated through our contemplation of the object itself.

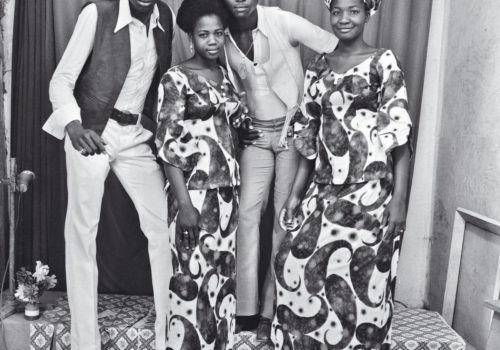

It is this, the significance of portraiture in our lives, that makes the work of photographers Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé so profound. Their ability to show us the lives of modern Africans forever changes our assumptions about the place in which life began. The politics of Africa are so tremendous it does not behoove me to try to frame them within this piece, but suffice to say the work of these photographer strips us of the assumptions, prejudices, and distortions that history has decreed.

There is something about being one of the people that one photographs that has authenticity. Not just authenticity, but authority. Both Keïta and Sidibé are from Mali, one of the poorest nations in the world. But you would never know this to look at their photographs for the people who stood before their cameras maintain a dignity that defies the worst of circumstance. Humanity, such as it is recorded in portraiture, is how we see ourselves in our own eyes—and thus we reflect our self-image back on the world.

It is in these reflections that two beautiful new books have been released: Seydou Keïta: Photographs Bamako, Mali 1948–1963 (SteidlDangin) and Malick Sidibé: The Portrait of Mali (Skira). Sidibé’s photographs cover the period of the early1960s through the 1980s, making these volumes a discourse on the continuity of people, photography, and portraiture created in Mali from colonialism to revolution to dictatorship. Democracy was finally established, but that was after these photographs were taken, so what we are looking at is people living in the shadows and aftermath of French occupation.

The Keïta book is a marvel. It stands at 17 x 12.3 inches, with 412 pages and over 400 photographs. It is as much a piece of furniture as an objet d’art unto itself. It is a timeless compendium of portraits, mostly unpublished, taken by the man who became Bamako’s most successful portrait photographer during the 1950s and 60s.

It offers us a glimpse into the space where the public and private meet. For no matter how carefully we compose our face, there is always something in the eyes that gives us away. There is desire, dreams, hopes, fears. There is who we think we are and who we wish to be. There is who we are with one another, and who we are when we stand alone. Seydou Keïta: Photographs Bamako, Mali 1948–1963 is a picture window into a time and a place that few of us know or understand or investigate for the mythology of Africa is so vast and grand.

Keïta’s portraits show us that all the world over, in any time or place, humanity is more alike than it is different. We know love and we know hate. We know beauty and we know ugliness. We know others in as much as we know ourselves, and when we look at these portraits, what we see is the the ephemeral forever caught by the eternal.

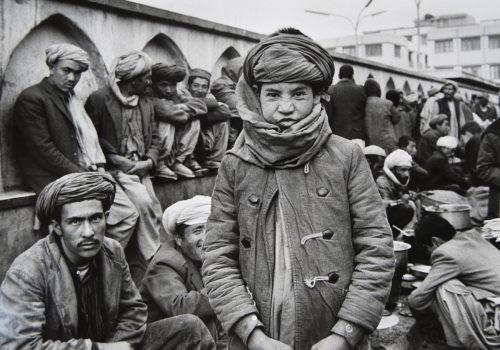

Beautifully complementing this volume is the book by Sidibé, a paperback book that offers us a look both inside and outside the photographer’s studio. Sidibé’s work is taken after colonial occupation ended and we see the people of Bamako creating themselves as in a new world. It is a space where traditions of the past meet the opportunities of the present, where one can create themselves in the space between. Sidibé’s portraits have an emotional intensity that can only be ascribed to the space in between the photographer and the subject, that one moment in time where eyes connected and energy was shared, and the spirit of life is forever caught on silver gelatin paper.

In going outside the studio, Malick Sidibé: The Portrait of Mali shows us a larger world, an environment and a context into which these people appear. We see Mali through the eyes of one of its citizens, and the Mali he knows is not the Mali that is reported to the world. This is a place of power and beauty and style, and though it may be among the poorest nations in the world, you cannot put a price on pride.

The work of Keïta and Sidibé serves a great purpose—to enlighten and inspire us with self respect and self love. To understand Africa is to understand ourselves. Let us begin by letting Africans tell us their truth.

Miss Rosen

Photographs, Bamako, Mali 1948–1963

Seydou Keïta

steidldangin, 2011

ISBN: 978-3-86930-301-7

The Portrait of Mali

Malick Sidibé

Skira, 2012

ISBN:9788857211251