The year is 1964.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964, abolishing racial segregation in the United States. Martin Luther King, Jr. wins the Nobel Peace Prize. Six days of race riots begin in Harlem. Muhammad Ali beats Sony Liston and is crowned heavyweight champion of the world. Malcolm X leaves the Nation of Islam. Nelson Mandela is sentenced to life in prison. Twenty one thousand U.S. soldiers are now stationed in Vietnam. Twelve men in New York City publicly burn their draft cards, the first such act of war resistance. A U.S. Air Force jet is shot down over East Germany. The Catholic Church condemns the Pill. The Beatles appear on Ed Sullivan. The Rolling Stones release their debut album. Goldfinger opens. Bewitched premieres. Lee Friedlander photographs cars for Harper’s Bazaar. Arthur Tress photographs San Francisco.

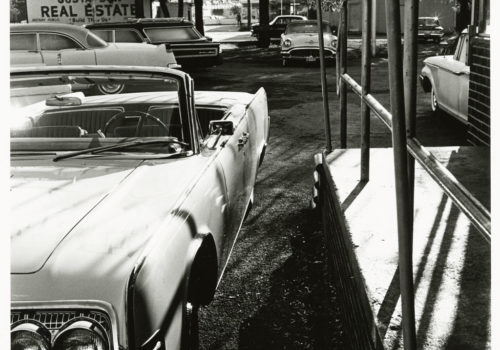

In 1964, Harper’s Bazaar was a dominant force, a space for original thought manifest in the minds of artists. In 1963, Warhol was tapped to produce the magazine’s annual car portfolio, which featured Pontiacs and Studebakers and silkscreened Coke bottles. The following year, Lee Friedlander was given the gig and the result of his work is collected for the first time in The New Cars 1964 (Fraenkel Gallery).

It is difficult for us, in the age of mass consumption and voluminous waste, to understand that in 1964, the next year’s cars were a Very Big Deal. Ruth Ansel, who commissioned Friedlander, notes, “Fuel was not a concern. Big was good. Automobiles were icons of glamour and an integral part of the fashionable world. Line, style, color, sleekness; these were the same elements that went into the highest levels of fashion of the time. The new cars meant optimism and elegance and the best of what America had to offer.”

Friedlander’s artistry lies in his ability to make the glamorous mundane, and the mundane glamorous. As Jeffrey Fraenkel notes in the introduction, “He had [the cars] delivered to parking lots near burger joints, gas stations, cheap furniture stores, downscale beauty parlors, an empty movie drive-in (during the day, no less), and, most ignominiously, a used-car lot. With no intent to subvert, Friedlander was already showing potential buyers what their brand new automobile would look like on the resale market. Pr, as Lee states it, ‘I just put the cars out in the world, instead of on a pedestal.’”

Friedlander’s distinctive approach did not appeal to the power at Bazaar, for they depended on advertisers, and back in the early 60s (much as the same as today), advertising dollars were sacred, conservative, and controlled the dominant narrative. Friedlander was paid for his work, and his photographs were put into storage and forgotten as years passed—only to be unearthed, and presented in this stunning monograph.

Fraenkel Gallery sets the bar for art book publishing by employing the finest in the industry. Design by Katy Homans, separations by Thomas Palmer, printing at Meridian under the supervision of Daniel Frank. The creation of an exquisite monograph requires a team of consummate professionals, people who see the production of the book as the creation of an art unto itself. In an age of cheap reproduction, farmed out overseas to a country that is notorious for human rights violations, cheap labor, and irresponsible environmental practices, everyone suffers from the politics of greed. To produce a work of art requires the greatest integrity. Friedlander and the Fraenkel Gallery understand this in ways that few others even begin to understand.

Not every book is a work of art. The purpose of a book depends on what its content demands. Published on the occasion of a major exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, Arthur Tress: San Francisco 1964 (Prestel) is the classic exhibition catalogue. It features an informed introduction that sets the stage to describe the convergence of a time, a place, and an artist’s vision. Imagine San Francisco bubbling. Imagine San Francisco as the site of the 1964 Republican National Convention that elected Barry Goldwater to run against Lyndon Johnson. It’s as shocking as George W. Bush in New York City in 2004. It is the most blatant comment on the disconnect between life and politics.

The spirit of the 60s was just being formed and the events of 1964 set the stage for what would come sooner than anyone realized. Yet Tress’s photographs reveal something that we take for granted, connecting us to the simplicity of humanity by showing us the American spirit. That spirit is the one that flits between individuality and conformity that holds on to the past while pushing forward endlessly. The America believes in their fundamental right to do and say and be whomever they like.

“America is the most grandiose experiment the world has seen,” decreed Sigmund Freud. Arthur Tress’ photographs reveal an understated and overlooked step in that experiment, for it foreshadows a transformation few could have predicted. In his photographs, we are confronted by humanity, by what appears to be normal, but is simply the surface through which we cannot see.

“San Francisco was a city of dissonance,” Tress comments and his photographs subtly reflect this. But they go further, beyond the time and the place and reach deep into the human spirit. Tress observes, “Recently I discovered something surprising while poring over one of the contact sheets: a single image of an object on display at the old de Young Museum, which was a very unusual subject for me to photograph. It shows a spiral relief in an exhibition of ancient Indian sculpture, which must have meant a great deal to me at that time. There is a Buddhist-Hindu theory where you don’t see your life as linear, going from point A to point B, but more as a spiral. At different parts in your life, the spiral touches itself; you come back to earlier concentric circles. And so a curious phenomenon of revisiting this earlier period of my work is how it is affecting the way I photograph now…. In a way, reliving the experience of making these photographs in the 1960s has helped me return to an earlier, enthusiastic, energetic self.”

Sara Rosen