The great Age of Exploration lead man around the globe, to explore the most remote parts of the earth seeking knowledge of Nature and of Self. Man is only limited by his imagination, and that’s what makes his work spellbinding: the possibility of going places we’ve never dreamed, of seeing the unseen.

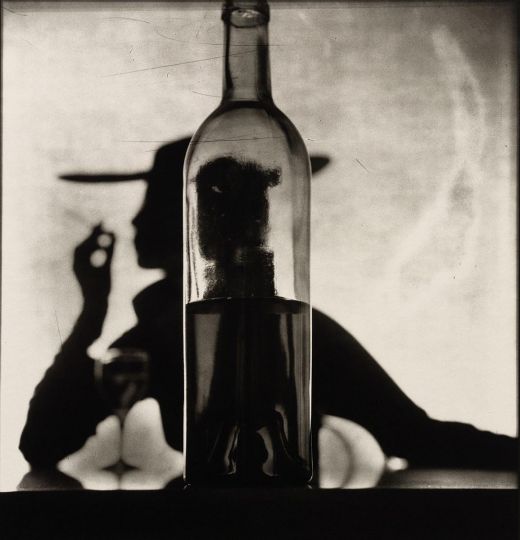

What makes the Age of Exploration amazing is that cameras were available to document the adventures in details never before seen. The camera’s ability to provide a sense of not just fact but also of feeling is what makes the photographs featured in South Pole an extraordinary experience.

South Pole by Christine Dell’Amore (Assouline) is an extraordinary piece of history, documenting the Terra Nova Expedition of 1910-1913. Although it is a piece of history learned by every British student, to the rest of the globe, the adventures of Robert F. Scott and his five-man team are here to, for the first time, unfold.

Arriving at the South Pole on January 17, 1912, the crew was greeted by their worst nightmare: a Norwegian flag. What happened next is even more horrific: they began their trek back to the boat only to die eleven miles from safe haven. South Pole presents excepts from Scott’s powerful diary alongside photographs from team member Herbert Ponting. The result is a volume that in unparalleled in its presentation, as twelve gatefolds are spread throughout the book, giving it the distinctive feeling of a landmark volume.

South Pole opens with forewords by His Serene Highness Prince Albert of Monaco and Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal, Princess Anne of Great Britain, and is immediately followed by a handwritten note by Captain Scott that is almost illegible. One can determine from his words that he was weakening at this time. And it is a strange thing to look upon the hand that is failing, knowing its dedication to the mission supercedes all, including life itself.

As Dell’Amore notes in her introduction, “As he lay dying, Scott penned his ‘Message to the Public,’ the clear-headed and poignant last words that would elevate the expedition to its legendary status, ‘Had we lived,’ he wrote, ‘I should have had a tale to tell of hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the hear of every Englishman.’” It appears that Scott’s wish came true, as their deaths did just as he intended.

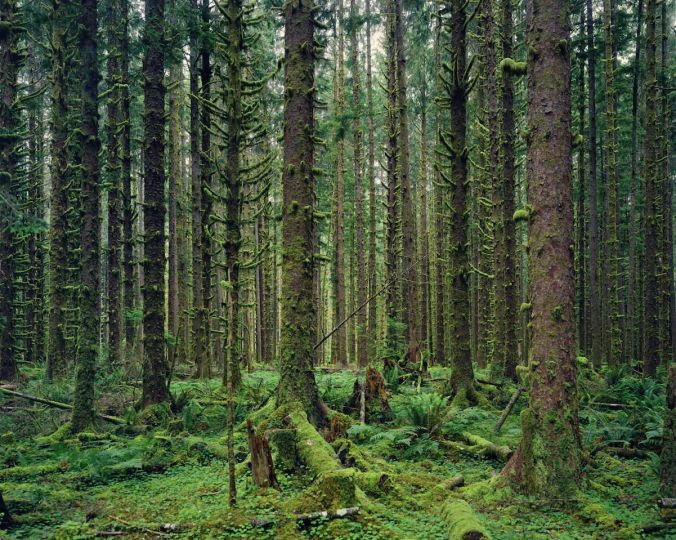

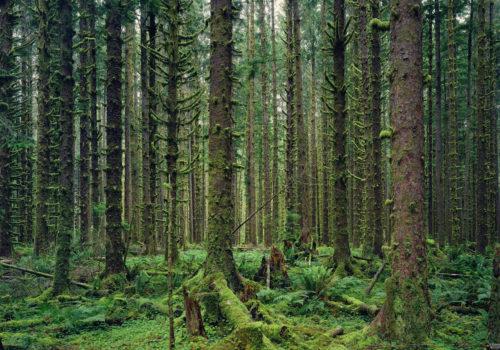

Knowing from the outset that the people we observe in these photographs are living their last days is a strange thing. It somehow elevates their experience to something mystical, smoothing more spiritual than the image itself suggests. We feel their singular dedication to their mission, and their willingness to put their lives on the line in order to achieve their end. And what is incredible is that they achieved it—but for them, second was not good enough, and that’s what makes this story heartbreaking. Yet despite this heartbreak, the story itself is captivating and it reminds us of a time when Man stood humble before Nature, looking to understand it through the act of engagement.

The photographs by Ponting add a layer to this story that could not be achieved by Scott’s words alone. They provide a window into the personal, the human side of an inhuman environment. There are photographs of glaciers, of penguins, of killer whales. There are photographs of seamen, of the ship, of husky dogs. The images create a sense of scale, a sense of scope, they provide a point upon which we can safely perch to observe all that Scott and his crew endured.

The book’s cover features a photograph of an expedition member sitting on a box in the snow enjoying a meal. It was shot as an advertisement for Heinz, one of the sponsors and it reminds us just how much life has remained the same—and how much it has changed. It is the matter of just one century, but what a century it has been. Remarkably, Scott’s last expedition base still stands at the shores of Cape Evans. An honor to a group of men whose heroism continues to inspire generations to greatness.

Sara Rosen

South Pole, Christine Dell’Amore

Assouline, 2012

ISBN-13: 978-1614280101