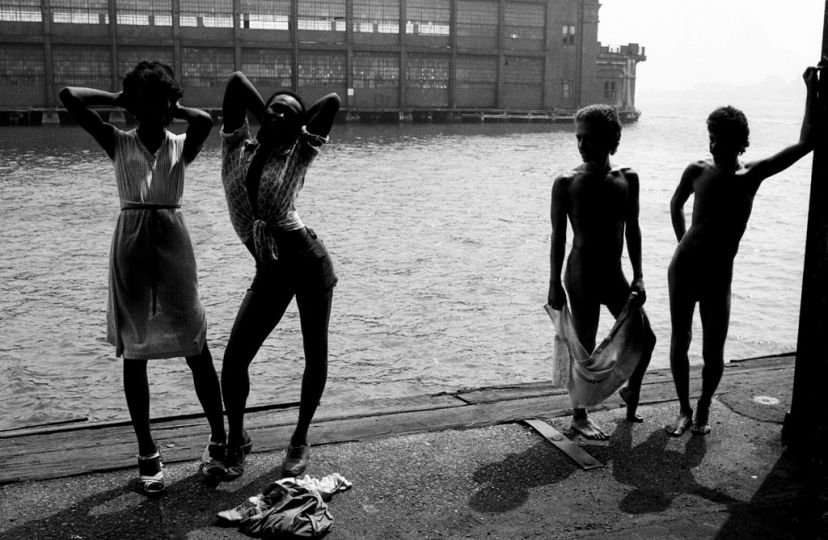

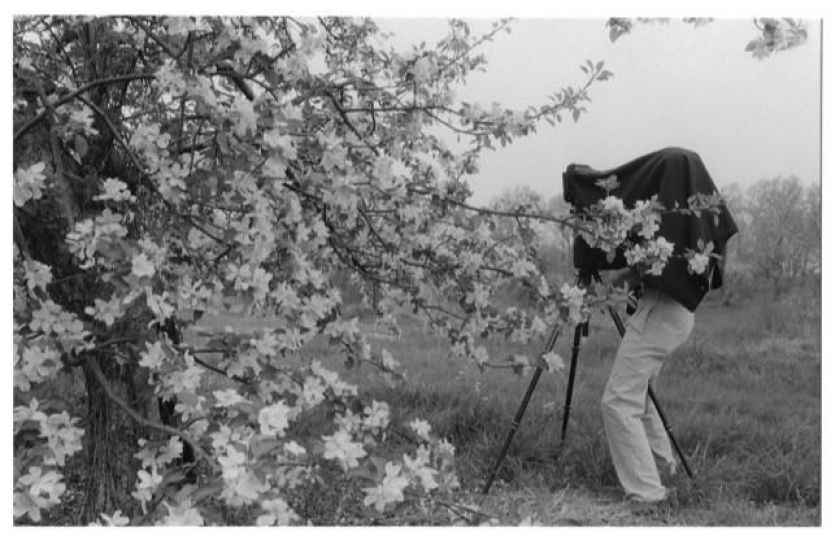

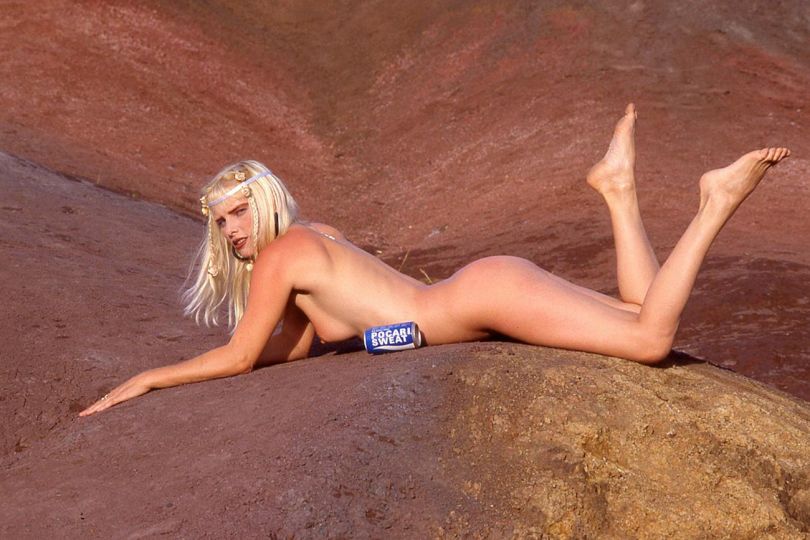

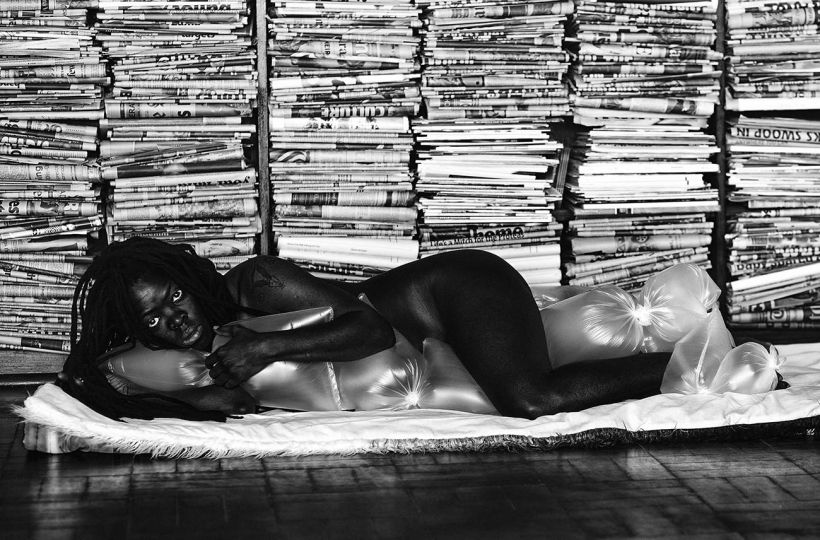

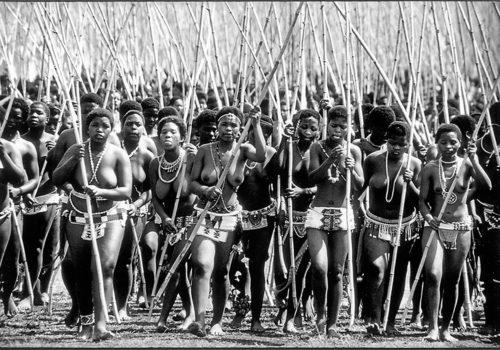

Opening on the 25th of March, the Cologne based Hardhitta Gallery presents a new solo-exhibition by the German artist Miron Zownir, one of the most radical photographer of contemporary times.

There are various ways of approaching the images of Miron Zownir. We can see them as the products of a windscreen wiper which, once set in motion, synchronizes with the shutter’s click. We could be dealing with a filthy junker, windows smeared with mud and grime. The comparison is cogent and apt because it tells us that it is the photographer who shines a light into the dark corners, that it is only through him that we are able to see into them. And just like a good window cleaner, he works carefully, boldly and thoroughly. However invidious one might deem the external circumstances and discovered situations, Zownir lets us peer through the opened chinks into the cities’ core. He claws the muddied windows clear. He gives us insights into secret passages, we gain knowledge of activities that nobody else offers us. His subjects are the shadow realms, the vibrantly alive haunts of the dead. We look into the deep interior of human places and, because we only ever peep through tiny exposed cracks, we gaze incredulously and breathless with tension, more alert, and, with every ounce of our attention, we perceive the slightest detail more intensely. Zownir takes us by the hand and shows us a hitherto unfamiliar world.

What would seem to me to be a better comparison than the windscreen wipers is that of a recourse to criminology. If we were to assume that Zownir, through his tireless work, has stumbled upon something that was not supposed to come to light, we would be correct. The city, man, humanity, whatever we are shown, would almost have gotten away with it, the file would have been archived and the cold case closed. The fact that this is not the case, that today’s Berlin, for example, is now confronted with its old habits, is solely down to the tenacity of Miron Zownir. This lone photo-journalist not only shows us exactly what really happened, how it happened and what was going on, but meticulously unravels it too. He does not simply leave the observed things in peace because he has visited those dark places, experienced the people in their cells. Now he is their sole witness. Even if we wanted to take up the prosecution’s argument and speak for the accused, as honorable as that may be, it would be of little use here: the evidence is simply too overwhelming, the conspiracy has been uncovered.

Attempts to turn perpetrators into victims and the victims, in turn, into perpetrators are futile. Zownir has made his silent witnesses speak. His pictures do not perjure themselves. His images are incriminating evidence. As deeply as Zownir, the contemporary witness, has infiltrated the material, as harshly as he sees himself exposed to all of the indecent accusations, the most harmless of those is that he is a liar and troublemaker. What we call grandiose or proud, the opposition calls provocative or embarrassing. What we find splendid, proper and true in his pictures, others rail against as shame and scandal. They want the witness in their dock. They want to twist the facts and arrest the photographer. But he is too much at home in the material for anyone to have anything on him. With the camera hanging at his broad chest, he appears well-informed and, in his artistic way, ready to assist the fact-finding mission. Creative justice must be obtained for every living truth.

We’re not dealing with a harmless city that lives up to its quaint name. Oh no. Berlin has its dark sides. Berlin’s skin is raw and covered in bruises. Berlin is spoiled, lecherous and wild. The nights are hot and irresistible. The people are bewildered and dissolute.

Like the shock pictures on cigarette packets, the photos should be displayed on giant walls and printed in schoolbooks, for they show relentlessly how deeply the city is involved in machinations and is anything but innocent. Zownir’s photos give us clarity and insights. They are like a large-scale campaign. They are witness statements shouting over one another, each incriminating the other. They are documents that one would have preferred to keep under lock and key, to withhold from the public. Some find that repugnant. They are disturbed by them. They are against Zownir’s steadfastness, accuse him of subjective zeal, and stubbornly deny that his pictures exist. To them, he is neither a hero nor a saviour. They don’t just rub their eyes in dismay, the statements the images contain rub them up the wrong way. But Zownir does not accuse, he only ever submits his photos in his subject’s defence. Of course, there are extreme images among them which stand out like bullet holes. Above all, they are evidence that provides important information about the time of the crime, about the sequence of events. We are drawn into something. We are in the thick of the action, present. They allow a particular attitude towards life to be precisely reconstructed.

The pictures help us to grasp the extent of what has happened, of what has taken place. They seem sufficiently incriminating. The great case seems closed, easily and quickly solvable upon first glance at the photos. That’s deceptive. We are deceived. We are dealing with disparate entanglements. Once we open ourselves up to the pictures, we become complicit, and more than that we lose our timidity and innocence. His reasoning is complex, fully formed, direct. We are confronted with countless situations. We sense that this photographer has undoubtedly seen more than he is obliged to say. Berlin is probably well advised invoke its right to remain silent for the time being. At other times, the city is incapable of holding its tongue. The weight of evidence of the photos is crushing. They are incredibly convincing. Zownir’s pictures are as telling as smudge marks, blood spatters, stab wounds or small scratches to the face. We can also speak of a necessary, incontestable photographic imperturbability.

The number of fresh clues is growing steadily. Berlin certainly won’t get off scot-free. Berlin just didn’t reckon with Miron Zownir – it thought itself untouchable. What a foolish error, and one which delivers us such wonderful pieces of evidence. These images don’t beat around the bush, they’re not looking to talk their way out of it – they don’t mince their words. No attempt is made to suggest, justify or even excuse here. The pictures provide crucial information. Where others would simply press the shutter, Zownir unleashes waves of indignation, he goes about with his camera like a hit man, he helps us to understand. And we enjoy joining him on the trail. Zownir wants us to find the perpetrators. He deliberately leaves clues behind. He wants to be recognized and convicted as a witness of the times, he wants to make us his accomplices. We cannot, should not and are unwilling to remove ourselves from the affair; we are compelled to look at that from which we would otherwise look away.

The wanted photo that we might put together of Miron Zownir as a photographer depicts him as a loner, a lone wolf, a recidivist. He works ruthlessly and sensitively against the inauthentic caricatures of this city. He knows all the tricks of the trade, he’s hard-nosed; he marches into battle against the optimists and releases his images like vexatious little sniffer dogs. Where Goya was visited by monsters in his sleep, Zownir testifies to monstrosities in a state of extreme wakefulness. He doesn’t work under cover. He doesn’t infiltrate the scene incognito. He exposes himself to the danger of being recognized as the photographer Miron Zownir. He wants to blow his own cover with his photos; in the best sense of the word, and in order to reap the fruits of his labor, he intentionally falls into disrepute. In order to draw the greatest possible audience to his unique case, he renders himself criminal. He is compelled to soil the freshly made bed. Learning to understand Zownir means coming to see him as a courtroom. His images feverishly await the seeing or looking process, and at the end of it there can be only one verdict: innocent on all counts.

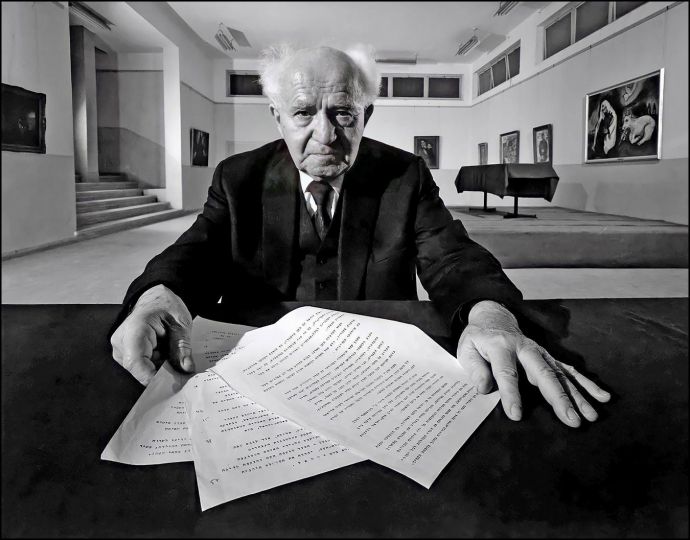

Peter Wawerzinec

Peter Wawezinec is a German novelist, writer, artist and poet who lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

Miron Zownir, Berlin Noir

March 28 to May 27, 2017

Hardhitta Galerie

Moltkestraße 81

50674 Köln

Germany

Book available on March 25.