My first trip to Mali was hard, bitter, sometimes sordid. What struck me most was the relentless struggle against constant aggressions: from mosquitoes, desert wind, filth, corrupt police, intense stares, being asked for so many different things that it bordered on harassment. I was worn out, disgusted, and wanted to shorten my trip and return as soon as possible.

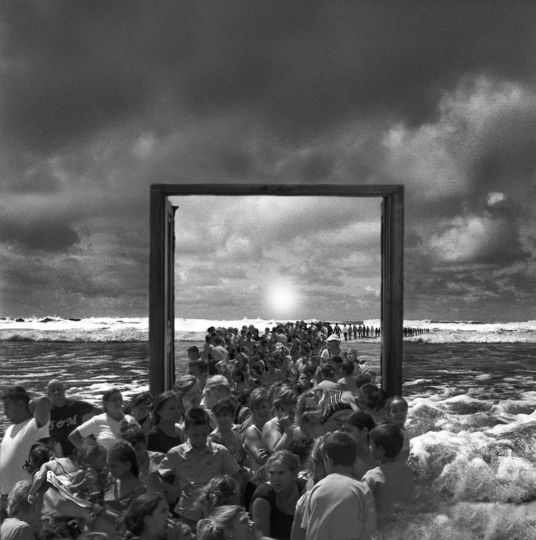

At the time I didn’t realize the subtle, poignant melody that filled my blood. The longer the trip lasted, the more the slightest detail seemed impenetrable. I mentioned it to my guide, Amako, the day we visited the mud-brick city of Djenné. He didn’t flinch, as if to confirm the mystery. Shortly after, he took me by the arm and directed my gaze: an entryway, a long dark corridor, a child in the shadows, then another in a courtyard bathed in light… and then something extraordinary, it was as though I was seeing the child in the light through a keyhole.

“To open the door,” said Amako, “you need a key… just a key.”

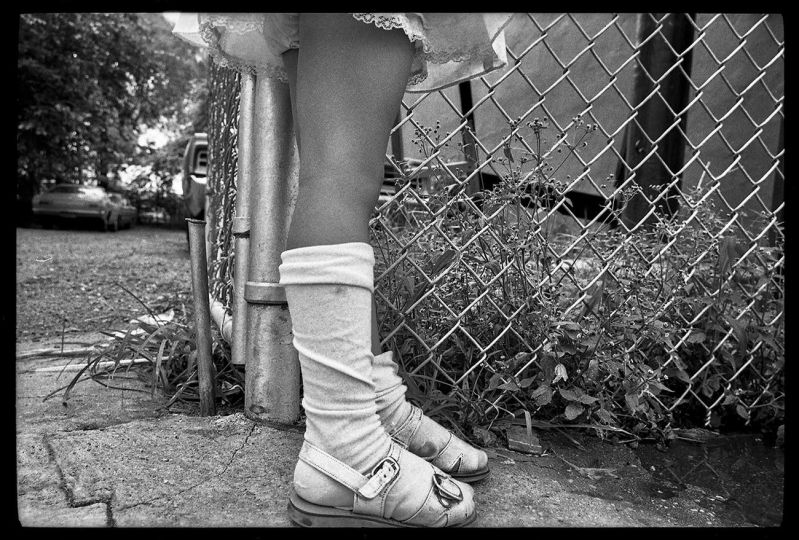

The three months that followed my return gave me, in the darkroom, the key that allowed me to see things clearly. The aggression had vanished . I was suddenly open to the beauty of things. Insignificant details took on a different appearance, tense situations were resolved by the arrival of an unexpected light, characters stood out against my newly discovered reality. The Sahel opened up my senses, and it suddenly was clear to me. The magic was there.

This is how Instant Sahéliens came into existence: in the distance, the darkness, and listening to Ali Farka Touré. And travel after travel, like a second chance not to be missed.

Eighty photographs and forty texts are the traces of that trip.

Michel Kirch

Read the full text of this article on the French version of Le Journal