My, oh my, how the world has changed since my last experiences of Miami Art Week were shared in 2018. The degree of change and struggle one faced during this pandemic is of course determined by one’s context and financial stability. Who has been pushed to the bottom, and who has come out on top? What has shifted and why? How does the world of creators survive? What’s for sure, is how fragile our foundations can be and how much a community isn’t a community when support systems fail. The egg has cracked, and the cracks have widened. “Class, race, gender based priorities that were invisible are now visible.” A place without the diversity of its people becomes lifeless, like a puttering engine that lost its hum. And what can we do to fix it? Vaccines had been made in record time. New platforms are starting to emerge. More museums and institutions have been working on improving the diversification of their teams to better represent their work and context. Online platforms have sold more art than ever before. And the chatter of NFTs has become the tinnitus in my right ear. As older structures break, new ones are being built. This pandemic shook so many of us, where we took a closer look at what matters. And for many of us, this included art.

Miami Beach Convention Center

I went upstairs and took the long walk that wrapped around the perimeter of the building anticipating Meridians to be on the 2nd floor like last time, only to find that this 2nd Floor which was once filled with spacious installations now had Joe’s Stonecrab on the right and the Conversations forum on the left. The cues on the 2nd floor ushered me downstairs to a tamer setting where digital screens flashing NFT art illuminated the first booth on my left.

This was an inevitable encounter as more artists jump on the NFT bandwagon and integrate digital art to sell online. Having the ability to grow and have direct contact with your supporting community, to have an expanded revenue stream and more transparency towards the provenance of your work is an exciting prospect. But the carbon output, the overall security and the maintenance of these current, digital platforms for the long run gives me pause.

Then, I met Mark Soares who runs and founded the company Blokhaus. They are one of many entities in the Tezos blockchain ecosystem, different from Ethereum. He addressed some of my concerns and shined a light down the NFT and blockchain tunnel which feels like the beginnings of new possibilities, that if used strategically, can benefit creators as a point of connection.

CYJO: I’ve heard of the proof of work NFTs for art on blockchains like Ethereum that’s energy intensive. For me, it’s a bit of a turn off. But Tezos, an energy efficient blockchain, sounds like a promising alternative. Can you tell us more?

Mark: There’s 2 types of blockchains – a proof of work blockchain that’s the traditional and standard blockchain like Bitcoin and Ethereum and a proof of stake blockchain like Tezos. Proof of work is much more energy intensive than proof of stake because the way you secure the network is through this complex calculation, and for lack of a better word, you’re essentially brute forcing the answer to a very complicated mathematical problem when you mint an NFT. This means you’re running processing power through a lot of expensive machines, and you’re trying to guess the answer to this mathematical puzzle to make this NFT. It uses a lot of energy.

Proof of stake is very different in terms of how it uses the network. Essentially it’s secured by the stake you put in. Everyone has a stake in the network and that means essentially that everyone’s participating securely. And if you misbehave as a staker or someone that’s contributing to the security, you actually get penalized. The incentives are in line to secure the network without the energy requirements. That’s why other platforms like Ethereum 2.0 are trying to move into proof of stake because it’s significantly more energy efficient. Millions of times less energy is used on proof of stake vs. proof of work.

With Tezos there’s something more special, though. They have self-evolving governance. What that means is as a participant, you can submit an upgrade proposal. You can say, “Hey, I want to add this feature or that feature or change these requirements on the blockchain.” And if enough people agree with your proposal, it automatically gets deployed. There’s an even greater level of transparency because all the decisions as to the future or protocol of the blockchain arrive at a consensus of all the entities that are validating the network.

CYJO: Having learned you worked previously for a major photography brand prior to Blockhaus, have the photographers you know embraced NFTs and added them to their portfolio of items for sale?

Mark: Many photographers in the industry I know are used to selling their end result much more than an artist who, let’s say makes a series of 10 paintings. This is because photographers can get revenue through usage rights for use of the work within a certain timeframe. And so the understanding of NFTs doesn’t always easily sink in. The first question I get from photographers a lot is about usage rights. What is the person buying? For some photographers, usage rights are a big part of their business model, and there’s more hesitancy. So, for the photographers, when you’re buying an NFT, it’s like buying a physical print, but the print is digital. If I buy a Picasso, I don’t have the rights to commercialize the image. I can exhibit it or put it in a gallery, but I can’t print t-shirts with the image. And it’s the same thing with the NFT. You own it. You can display it. But you can’t sell the digital image to National Geographic to use in their March issue. The artist still retains the rights to the image. It just happens to be recorded on the blockchain as an NFT. And there’s information there that allows the photographer to say this photographer really did capture this image. It is part of their portfolio. It’s real.

CYJO: There’s a lot of talk about community building with NFTs. It’s more than just a digital image on a blockchain.

Mark: The focus that I’m seeing from artists is driven towards community building. And a lot of artists are switching their mindset to – if I’m selling an NFT, I’m essentially selling into future engagements or future activations with this group who buys my NFTs. Essentially, NFT’s are a point of connection. For every brand or artist out there, they want to use NFT’s to activate their fanbase where their NFTs can offer exclusive experiences to their collectors in the future. It’s a way to go back and reward people because proof of ownership is proof of fandom. Proof of fandom means you have access to activate these passionate users. That’s one trend I’m seeing, but it requires a bit of forethought and planning when you’re creating them, because you have to think longer term. If you’re entering this platform thinking you’re going to make a quick buck, collectors are not going to fall for that. They want commitment, passion and authenticity.

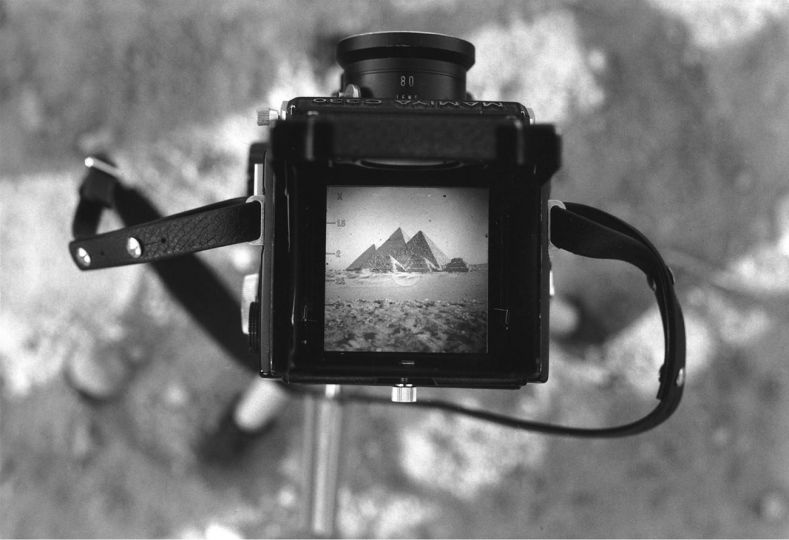

Also, the photographic world, with blockchain and photography, go hand in hand to me because cameras have been used as record keepers of truth and blockchain does the same thing. And in a world where deepfake images are so easily created, it’s harder to tell what’s real and what isn’t. I find it fascinating that the two worlds haven’t fully combined yet.

CYJO: Are NFTs here to stay?

Mark: NFTs are empowering creators everywhere, both financially but also creatively. I believe that the artwork being spawned by this new wave of creators deserves respect and credit. And it’s one of the reasons why we’re here, to help shed a light on that. It’s not just “crypto art”. There’s a real movement, and I think it will be appreciated for a long time to come.

Images: 1, 2

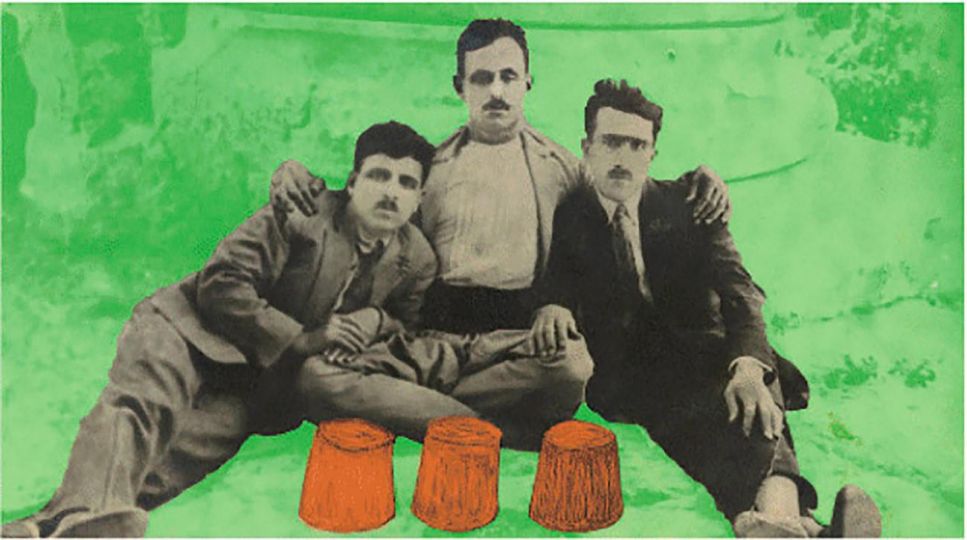

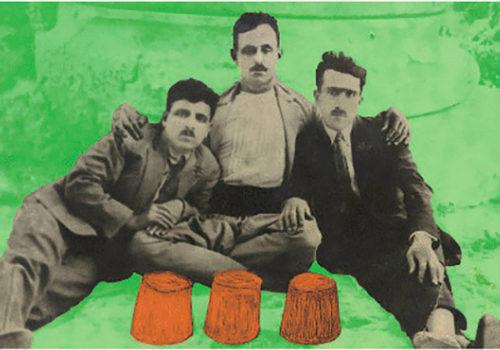

Behind the NFT booth, the expansive scale (over 30 feet in length) of Todd Gray’s Sumptuous Memories of Plundering Kings, 2021 drew me in. “The concept of ‘mental colonialism’ forms the bedrock of Todd Gray’s conceptual photography. From the outset, the term photographic sculpture might come to mind, but such categorization belies the undercurrent of the strategic deception at work here: What would otherwise be the focus of an image is more often than not concealed by Gray’s resolute composition of stacked imagery. This work connects with the renewed contemporary discourse, where past and present transgressions are confronted head on.” Todd, born in 1954, lives and works in Los Angeles and Gana.

Image: 3

Soon after, I walked into June Clark’s work, Harlem Quilt, 1997 at Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto. Madeleine stepped in to tell me about her work.

Madeleine: June was born in 1941 in Harlem and moved to Canada in 1968. There was political turmoil in the US, and her husband at the time avoided the draft. And so she moved with him quite suddenly and tried to find her place, her community that resembled what she had in Harlem, which was so important to her. She started taking photographs in Canada and worked as a documentary photographer. She sought out street scenes to situate herself in her new environment. And then in 1997, she did a year long residency at the Studio Museum of Harlem. And that’s when she made this work. These are all photographs she made in the streets of Harlem. She was shooting with her camera at waist level to get candid shots, but then she also realized it kind of resembled a child’s perspective, a perspective of Harlem she experienced growing up there. The over 200 scraps of fabric was sourced from a Goodwill Store from 125th street. And there’s this nativist idea that someone in one of these photos might have once worn one of these pieces of clothing because it is such a close community. The last time this work was shown was in 1997. We’re glad to be showing this again this week.

Images: 4,5

I gazed at Bruce Conner‘s set of punk photos taken in the 1970s and 80s . Twenty-six photos were attractively arranged on the wall of the Kohn Gallery booth. It unlocked memories from my high school days, wearing plaid, army green and red lipstick, tromping around in combat boots, during a time where Fugazi was in its heyday. I was too naive to understand back then how much those combat boots traumatized my father, bringing back his memories of the Korean War.

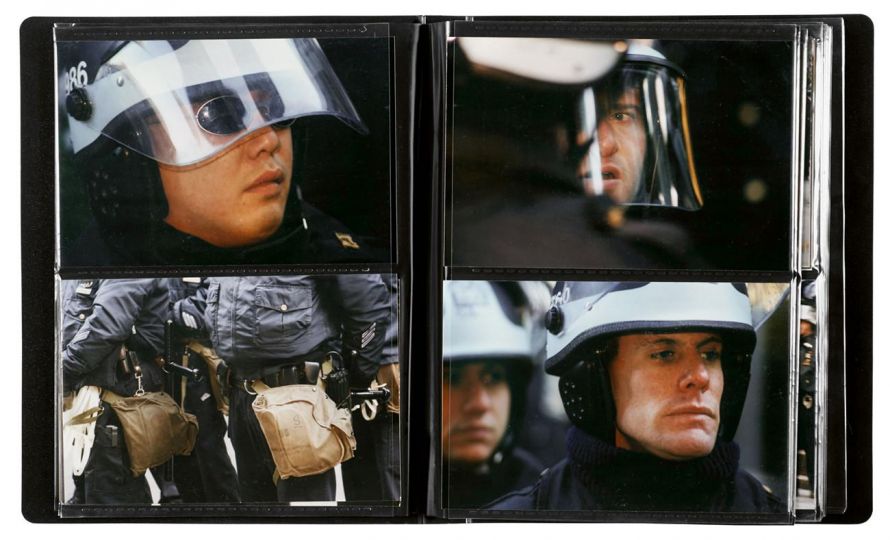

Other attractive arrangements from a series that I saw were from Barbara Kasten’s Variations 1 – XVIII, 2021 with her cyanotype installation and Sunil Gupta’s Lovers: Ten Years On, 1984-1985 at Hales Gallery.

Images: 6, 7, 8

Warming up to familiar photographers like Cindy Sherman at Spruth Magers, Gordon Parks at Rhona Hoffman Gallery and Thomas Struth at Galerie Max Hetzler felt like I was saying hello to an old friend.

Images: 9, 10, 11

And then Princess Leah caught my eye or was it an Indigenous woman? It was both. That drew me into the booth of Peter Blum Gallery where I met Kyle.

Kyle: We’re looking at Nicholas Galanin’s Things are Looking Native, Native’s Looking Whiter, 2012. On the left side of the image is a Hopi Woman by Edward Curtis. And on the right side is Carrie Fischer from Star Wars. So, Galanin is taking these two different images and putting them together. From the right side, you can see the borrowing from Indigenous culture that came into this white, futuristic character. And now, he’s also saying that this borrowing of culture is actually working in reverse too, that a lot of natives are taking characteristics of white people in regards to how they look as well. This work represents the back and forth of these messages. And a lot of his artwork deals with these issues.

We walked over to a photograph of Nicholas’ other work.

Kyle: This is an installation Nicholas did for Desert X which was this summer. It was outside of Palm Springs for the Biennial. It’s actually titled Never Forget, but it says, “Indian Land”. And it’s executed in reference to the Hollywood sign which was very exclusive for mainly white people. By placing this sign here, he was reclaiming and reminding people about his history. It’s also in reference to the Land Back movement which is raising money for Indigenous communities to reclaim this land.

Images: 12, 13

Further down, Frida Orupabo’s eye-catching installation using archival images added to the growing works I’ve been seeing using manipulated archival imagery as a tool to confront, engage and present our histories to bring better understanding of ourselves and our present times. The Stevenson Gallery spoke about her work.

Stevenson: Frida is a Norwegian artist of Nigerian descent. And her background is what brought this whole work together. In 2013, she started an instagram page to share archival images of colonial history as more of a personal project. It was also open to some viewers that bumped into it. And then, Arthur Jafa saw it, and it became really big. Frida started making these big collages, and it exploded in the last year. It’s only been a year that she’s been a full-time practicing artist. She was a social worker. That’s where her heart lies as well. So, she combined those two practices doing social work and creating art for a while before she stepped forward into the art practice full time. Her work explores questions related to race, family relations, gender, sexuality, violence and identity.

Images: 14, 15

More beautiful work from familiar photographers were found at Edwynn Houk Gallery who exhibited works from Sally Mann, Lewis Hine, Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. This shot Dorothea took is titled Waterfront Protest, San Francisco, 1934. I’ve always loved Dorothea and her devotion towards capturing social issues of her time, but I ended up loving her even more after seeing her exhibition in Paris – “Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing” at the Jeu de Paume. Her extensive solo-show featured her work from the Farm Security Administration, the Depression Era and the Japanese American internment during World War II. It was at this exhibition where I had my first encounter with her work documenting the internment camps. I learned about how she was hired by the U.S. War Location Authority to document the relocation process of Japanese-Americans in the Pacific Coast area. She put her career on the line by publishing some of these photos to help share what was happening.

Images: 16, 17, 18, 19

Text by CYJO

CYJO is a Korean American artist based in Miami who works mainly with photography. Since 2004, she has been exploring the evolution of identity, questioning notions of categorization, and further examining our human constructs within her work. CYJO’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues which include The National Portrait Gallery (Smithsonian Institution), Asia Society Texas Center, Venice Architecture Biennale and Three Shadows Photography Art Centre. Her last solo exhibition was at NYU’s Kimmel Windows | Art in Public Places (2019-2020). She is the co-founder of the Creative Destruction, a contemporary art collaborative founded with Timothy Archambault in 2016. www.cyjostudio.com @cyjostudio