Ciudad Juarez in northern Mexico has made headlines of decades, known as one of the deadliest cities for women, who died there in large numbers for reasons which remain unknown. Twenty years ago, a large number of Mexicans began to arrive, drawn by the opportunities promised by its infrastructure.

The reality proved less golden. The Mexican workers were forced to compete with Asian immigrants, who drove down wages dramatically to less than a hundred dollars per week, in a city where the cost of living is comparable to that of the neighboring United States. Added to this social fragility is the ruthless drug war, which kills over 300 in the bloodiest months. The tension is palpable, permanent and cruel for the citizens who have chosen to remain here despite the danger and inevitable presence of death.

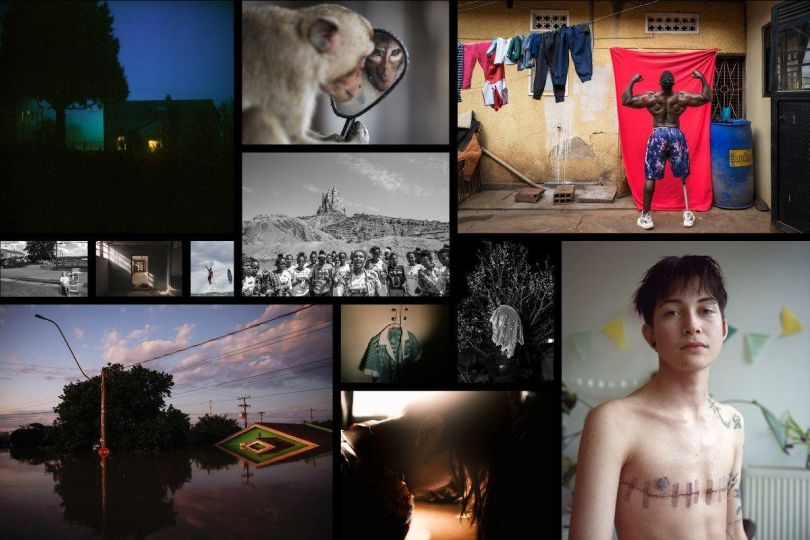

The disturbing photo reports on the city are stained bright red with blood. Only a few have exhibited a less gory aesthetic approach. Recently, two Mexican photographers have attempted to break free from this iconography and focus instead on the citizens and the reasons they have decided to stay. The first is Alejandro Cartagena, some of whose photographs were exhibited at the Bronx Documentary Center in January. The second is Luis Enrique Aquilar, a photographer and the director of the Gimnasio de Arte y Cultura, a cultural center, in San Cristobal de la Casas, in Chiapas.

The latter plays with the confrontation between landscapes and portraits. On the one hand—although the juxtaposition isn’t literal—are abandoned landscapes marked by the incomplete expansion of local industry: factory smokestacks seem fragile against the monumental surroundings, the mountains unshaken by the human violence. The red cross on the roof of a supermarket cannot be missed, but it seems as though this infinite city has taken away the its metal’s power to resonate. Neither the explosive violence of the cartels, nor the corrosive voice of industry interests Aquilar. He listens instead to the residents, who share their hopes with sincerity, profundity and spontaneity when he asks them to pose in the midst of this place they call “home.”