“Photography for me is improvisational, it is creating something new in the moment, creativity that is disciplined, emerging in real time. A great photograph breathes, it is alive, has body, emotion, and it is timeless.”– Herb Robinson

Music, Jazz in particular, has been an important influence on legendary photographer Herb Robinson’s working style. I wanted to get to know Robinson better as an artist before embarking on this journey through his new monograph, METRO / New York / London / Paris, published by Schiffer. However, I quickly found out he does not like talking about himself and will go to any lengths to avoid doing so. Fortunately Herb’s long time friend, photographer Leslie Jean-Bart, stepped in to help by dictating his answers to my inquiries with great success. In his own words….

~

It started early, when I was 9 years old. I was looking at and listening to the great Duke Ellington band. I was absorbing the music though I was not aware of it then. I was a good friend with the Hodges family who lived across the street from my parents at 555 Edgecombe Avenue. The building was famous for the great musicians and other prominent African-Americans living there, including Thurgood Marshall, musician and composer Count Basie, boxer Joe Louis, singer and actor Paul Robeson, among others.

My friends and I had access to seeing Mr. Hodges perform, hearing him practice in his home. I had the privilege to hear the purest, richest, beautiful alto saxophone sound that was Johnny Hodges of the Duke Ellington Band. The experience was like having the opportunity of seeing Michelangelo at work. I absorbed his sound and his tone while hearing him practice and perform. This was the period that was to form my photographic vision.

My peers were also Jazz musicians. My friends Johnny Hodges Jr. and Michael Lambert, were both Jazz drummers. I would go to their homes and sit until they finished practicing before we could go out and play. We were steeped in hearing and collecting Jazz records, like other kids collected baseball cards.

Though I was not a musician, I had access, understood, and connected to the soul of Jazz musicians. Circling back to Duke Ellington, he had a profound effect on me, though I did not realized it until I opened my first commercial studio.

Ellington was the ultimate composer where each of the instruments is used to serve his purpose. In my studio I had up to 18 different light sources at my disposal to be used as needed to achieve the goal at hand. That approach came directly from Ellington’s style of orchestration. For example, as to whether he used the sweet sound of a Johnny Hodges or the rougher sound of a Paul Gonsalves (tenor saxophonist) or mixed the two. Ellington’s influence extends as well to my street work, where it can be found in my use of and mix of textures, tones, and highlights that are used to serve my purpose, as an extension of my voice.

My favorite pianist, Bill Evans, and his use of negative space is something that I voluntarily, and more often involuntarily, channel when I am shooting. There is a lot of use of negative space in my compositions and Bill Evans is the main source.

~

Roy DeCarava, the Director of Kamoinge in the early days of the collective, was steeped in all the Arts. From him I get the seriousness, dedication, and respect for the Arts— the timeless of Old Masters. Not just composition, but all of it.

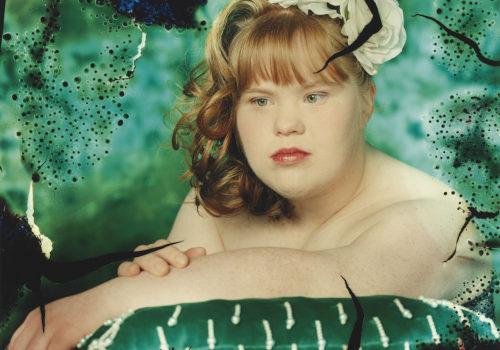

There was not any one photographer who influenced me. The influence on my work is more from painters, more specifically Peter Paul Rubens, Caravaggio, and El Greco. The Rubens and Caravaggio influences can be found throughout METRO in the energy and movement within the frame. El Greco’s is in the way I use line in METRO. In my portraits, I go beyond the surface of what I am seeing. I know a bit about painting, but as a photographer, not as a painter.

The abstract painter Joe Overstreet (he passed away in 2019) was a wealth of information. Not only because of Joe’s own work, but also because he was able to mingle with the key artists who influenced the history of modern painting in the United States. He rubbed shoulders with Willem de Kooning, Norman Lewis and all the other modern masters during their prime, so he has a wealth of information. I have really the privilege again, the honor to really learn from one of the living masters of painting.

As an artist, I have been inspired throughout my career by Pablo Picasso, and the person that I view as his creative equal, Miles Davis. Each of their careers was marked by their relentless drive to innovate and continually reinvent themselves, requiring a level of confidence and creativity at the highest level. Picasso and Miles knew no boundaries, defied convention, and were fearless in embracing new ideas, and then just as quickly shifting in new directions. They were undeterred by expectations that their work stay the same, possessed only by their art and rising above at an unfathomable level of creative genius. Both Picasso and Miles were masters of self-promotion, never faltering from their belief in themselves and the worth of their work; they were decades ahead of the ‘branding’ surge in advertising. Prolific beyond what appears possible in a lifetime, each piece of art was left for the world to continue to try to grasp and more fully understand in future generations.

Inspired by the lives of Picasso and Miles, I strive to move boldly in my ever- changing photography, taking risks and rejecting the need for a safety net. I am intensely focused on freely creating art from the inside out, often startling myself by what emerges. I am deeply fortunate to continually learn from these masters, whose genius illuminates my path.

~

It’s been a treat for me to listen to Leslie Jean-Bart discuss interviewing Herb Robinson with my questions. Going off on a tangent is really second nature to Herb’s character, and every story he tells is a small facet in his own life that results in the images he creates. Leslie described one afternoon as an example; “If Herb is talking about Art Blakey, he cannot just talk about Blakey. He has to refer to Philly Joe Jones style of playing as compared to Blakey vs. how Tony Williams was really a Rock drummer who happens to play Jazz, to Jack DeJohnette. From the drummers he will float to Jackie McLean style of saxophone playing vs. another particular Jazz saxophone player. From there possibly shift to Miles Davis’s style of trumpet playing, leading to Bill Evans style of piano playing, and then shift back to Art Blakey and the other major Jazz drum players. In his eagerness to clearly present and explain the finer nuances of certain aspects of Jazz, one can often find yourself in sensory overload. I have to often then “kindly-abruptly” stop him and redirect him where I need to go. Although his eagerness is honest, I came to realize that these long detailed explanations tends to often happen when he is desperately trying to avoid talking directly about himself.”

“A question directly addressed to him can easily start a discourse on Roy DeCarava’s life. No, Herb, I want to talk about you. “Well, well, Leslie”, he would say, “I have to set it up first, that’s the way I am”. He will then start with some cryptic half answers that one has to attempt to decode while he is sliding into Jazz or so other person’s life story.”

Clarifying his “Tony Williams was really a Rock drummer who happens to play Jazz,” exactly what Herb meant was that Tony Williams came along at a time when his generation was exploring the new phase of music at the time, and that was Rock. So Williams’s influence was more Rock. Williams and those of his generation were at the time in the process of leaving behind the platform set by the older Jazz generation, a platform that was more metronome and rhythmic, for the Rock platform that was harder. The same generational evolution took place with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie who played in the same band and were the inventors of Bebop 3. They both came out of playing in the Big Band, which was mellow and went into Bebop that was harder and more like Rock. The only one who did not fit into that evolutionary pattern was Miles Davis. He was a one man visionary. He did not stay into one idiom as most of his contemporaries did. Miles moved through different periods – Cool, Fusion, and so on.

~

To complete this look behind the images in METRO / New York / London / Paris, I asked Herb what drew him into the New York subways, the Paris Metro, and the London Underground (Tube). His reply was basically that the three cities covered in METRO played, and continue to play, a huge part in Jazz history.

Also, ideas like globalism, immigrants, immigration, and migration that were running on my mind, were all present and contained within a subway car. The subway car became an equalizer, a self contained common ground for all people regardless of their background or place of origin. It became portraits in the train.

I feel completely free to take the viewer on a journey with the camera as an instrument while using the Jazz idiom of improvisation. The story called me and took me on a journey where it flowed.

METRO / New York / London / Paris. Photographs by Herb Robinson. Curated and Edited by Eve Sandler. Schiffer Publishing, 2022

Herb Robinson is an original member of Kamoinge Workshop, the pioneering photographic collective of New York-based African-American photographers, founded in 1963 at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement. The name literally means, “A group of people working together” in Kikuyu. Robinson’s work was also part of the traveling exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, originating at the Tate Modern. He is represented by the Bruce Silverstein Gallery, NY.

Eve Sandler is an interdisciplinary artist, designer, writer, and activist whose work commemorates Black culture, memory, and transformation.

Leslie Jean-Bart, has walked the shoreline of Coney Island for the last 12 years, looking for the magic of light, water, and reflection, in his photographic series Reality & Imagination.

Elizabeth Avedon has been a long-time contributor to The Eye of Photography.