Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle, The Netherlands (location Castle Nijenhuis), exhibits Relics of the Cold War by Martin Roemers (b. 1962) who, between 1998 and 2009, photographed the decaying physical remains of the Cold War. He did so under the assumption that this bleak period had been consigned to the history books. But the apparent flaring up of old tensions has recently given the series an alarming topicality.

The Cold War is over – yet signs of it still exist. For four decades the Iron Curtain divided Eastern and Western Europe. An arms race was unleashed, nuclear bunkers were built, and everyone prepared for the worst. Photographer Martin Roemers, winner of two World Press Photo Awards (in 2006 for The Never-Ending War and in 2011 for Metropolis), spent eleven years (from 1998 to 2009) seeking out the remains of this period, travelling through countries that were once enemies: Russia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, Germany, Britain, the Netherlands and Belgium. His Relics of the Cold War series is the result of this search.

The photographs show preparations for a Third World War. The traces of this nuclear war that was never fought can still be seen in the landscape. Roemers explored and documented abandoned bunkers, underground tunnels, old military barracks, rocket launch sites and rusting tanks. He presents his subjects as quiet monuments to a bygone era. Looking today at these relics, the paranoia and aggression of that time are still tangible. Relics of the Cold War serves to remind us how it was and how it could be again: two opponents building the same defences out of the same mistrust and fear.

The catalogue Relics of the Cold War is published by Waanders & de Kunst.

152 pages, 74 photos. Text: English/Dutch. Introductions by Nadine Barth, H.J.A. Hofland, Ralph Keuning and Martin Roemers. ISBN 9789462623057

Essay by Martin Roemers (from the catalogue)

‘Same Defences, Same Fears’

Summer 1983. I’m doing my military service in the Dutch army but I’m on leave at the moment. I’m on holiday with a friend in Germany. We’re walking eastwards through a wood; it should be over there. We see something greyish through the trees. We can’t go any further: there’s a high concrete wall in front of us. There’s nothing else to see. Except for the singing birds it is quiet. We walk along the wall a bit further until we get to a watchtower with a soldier inside who’s looking at us. I take a photo of the man in the tower and he takes one of us.

We’ve still got time before I have to be back at the barracks and so we drive to West Berlin, mainly to see the nightlife. We go to East Berlin as well. I buy a postcard on Unter den Linden with marching soldiers from the East German army on it. I address it to my army unit in the Netherlands, writing “My transfer’s almost sorted” on the back.

A couple of weeks later, I’m back at the barracks and I get a visit from the Military Intelligence Service. The MI officer asks me about my visit to Berlin. Why were you in East Berlin? Who were you with there? Did you speak to anyone in East Berlin? What were their names and what did you talk about? Finally I sign a declaration and the officer goes away.

Autumn 1990. The Berlin Wall has fallen. I’m a photography student at the Academy of Arts. I drive through East Germany in my old car, passing countless Russian barracks buildings as I go. It looks like a totally different world from the outside; I wonder what they look like from inside. I walk to the front gate and ask for permission to take a few pictures. “Nyet,” they say.

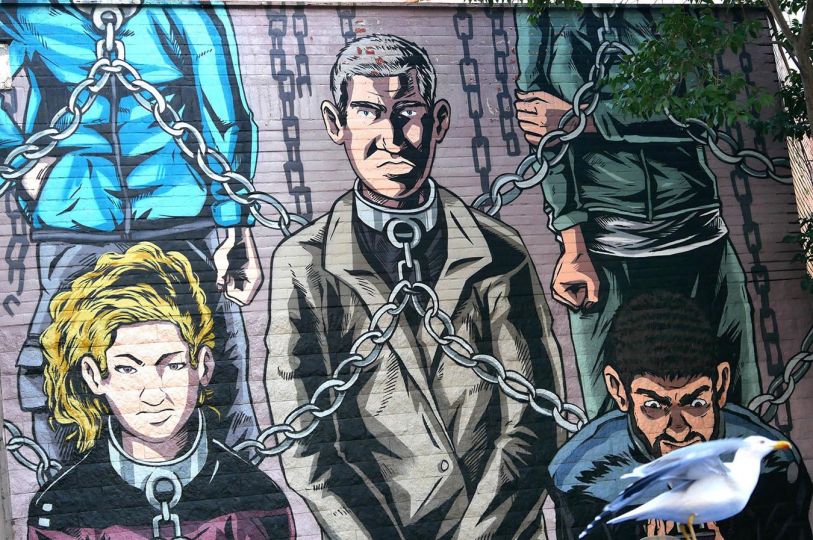

Winter 1998. I’ve started the project called Relics of the Cold War and I’m in contact with Ulrike. She works for an organisation in Brandenburg that manages the former Russian army sites. Ulrike gives me a pile of official documents with lots of signatures, seals and stamps. I’m allowed to go anywhere. I walk around, absolutely astonished. The local population plundered the buildings the moment the Russians had departed. What remains is the beauty of decay: buildings that are about to collapse, old vehicles, car tyres, an aeroplane and a peeling mural of the glory of the Soviet Union. This is the Disneyland of the Cold War.

Autumn 2002. Kaliningrad. I drive through a sleepy provincial town and see a small, old and dilapidated military building. I grab a camera and tripod and take a few pictures. When I walk around the building, I see two Russian soldiers lying on the ground drinking beer. I decide to go back to my car, but it’s too late. Two guards grab me and take me to a barracks. I’m held there the whole day because I have to wait for an official from the FSB – the former KGB – to come from the capital. Late in the afternoon, a fat FSB officer appears with tea and biscuits. He subjects me to a long and protracted interrogation. I tell him about my series of photographs of the landscapes of the Cold War. He accepts my explanation and writes a report of the interrogation. The final sentence reads “Mr Roemers has behaved impeccably and courteously the whole day.” I sign it and can leave. Minus my films, though.

Spring 2009. I’ve taken the last photograph for this project in Moscow. The question I’d asked myself for this series was “How has this war that was never waged affected the landscape?” I’ve looked for these places for eleven years, in between all my other work. At first, I focused on the Soviet legacy in the old German Democratic Republic, but gradually the project became bigger. Although the Cold War affected several continents, I restricted myself to Eastern and Western Europe. I’ve been astounded by the enormous numbers of bomb shelters, bunkers, air fields, shooting ranges, barracks, missile bases, border barricades and radar stations. They look identical on both sides of the Iron Curtain: the same defence mechanisms built because of the same fears.

Autumn 2019. I drive home from Berlin, stopping on the way at the Soviet Army cemetery near Potsdam. I took some photographs here for the Cold War project at the end of the nineties. Uniformed men and women watch me as I stroll past the graves. A lot more graves have photos on them than I remember. The bleached and rusted portraits are flanked by engraved Soviet tanks or aircraft. Then I see a familiar grave: Anastasia Tarakanova (1909-1948). There’d been a hammer and sickle and a red wreath around her photo, but only the contours in the stone are visible now. On her coloured enamel portrait, she is wearing a white blouse and earrings; there’s still colour in her cheeks. Anastasia Tarakanova is still just as beautiful as when I photographed her twenty years ago.

Martin Roemers : Relics of the Cold War

From 18 January – 5 May 2020

Museum de Fundatie

Zwolle, The Netherlands (location Castle Nijenhuis)

https://www.museumdefundatie.nl/en/martin-roemers/