“In the mind there is an awareness of perfection” – Agnes Martin.

First, it must be noted that Marc Valesella could have been a musician or an engineer in equal measure, and a great one at either . His wife Gaia proudly points out the exquisite sound system which Marc built from scratch and an impressive collection of rare LPs. A finely tuned taste is a taste in everything.

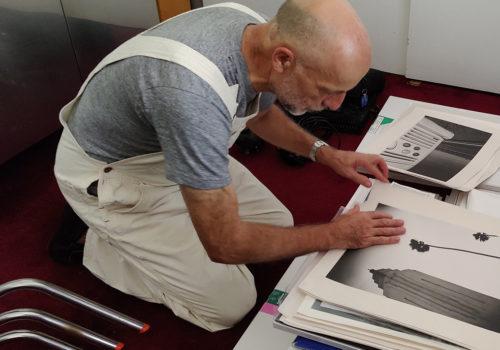

And Marc’s taste is as impeccable as the precision of his knowledge of instruments—from the enlargers and cameras to the lenses, it is immediately striking. The sense for aesthetics and science are balanced to make him the greatest printer of photography I have ever come across. Be that his own work or the work of other photographers who do not print their pictures, each image comes to life, to its best version of self: radiant, dramatic and subtle, mysterious and revealing, for Marc is a radically endangered type—a true master.

Some time ago, and it is hard to pinpoint exactly when that happened, many prominent artists, collectively, decided to forgo their commitment to the high art of craft. For the photographers, it became a dangerously shortsighted choice. The ability to photograph with ease delivered at first many amateurs and then everyone else (some seven billion cell phone users) straight to that exclusive artistic circle making its members hang onto the obscurity of their captions for dear life. Artspeak (the artworld’s version of the Doublespeak) became the only tool of distinction.

The arguments Marc Valesella makes about these issues are eloquent and instinctively persuasive. Yet what truly wins the day is his work: when a photographic print holds your attention and lingers in your mind, all objections are laid to rest, forget the clever ruses and the trends.

The reproduction of his prints online does not do them justice because all images on the screen are, in fact, flattered by the light behind it and that adds contrast and luminosity, so pictures appear more vibrant no matter how dull. Looking at the screen is a bit like watching a small fireplace—it’s mesmerizing. Jeff Wall made a point of it setting up dreary landscapes into light boxes. Which is why seeing the same image in print can sometimes be a crushing disappointment. Strangely, prints by Edward Weston or Irving Penn or by Marc Valesella are better seen in the original than on screen. Very rarely do you see a print that glows on its own—on paper—made in the darkroom. Mastery goes into it. Yes, knowing chemistry, optics, papers, various processes is self evident. Yet the technology has to become a sixth sense. How to balance the picture? What is the photograph about? What must it reveal, what must it hide to have the most impact? What does it say?

There is something else. A truly great printer must possess a generosity. Behind the rarefied craftsmanship and strict rigor (not exactly an egalitarian commitment) there lies a thrill at seeing beauty made by others and a desire to bring it to full bloom, to give its complete potential.

A full disclosure: I learned darkroom from Marc and we have been friends for twenty years. We have talked shop all this time. Some of these conversations are here.

Marc Valesella: At this point of time, thinking about photography is very different. It is different how people even handle their tools—cameras—instead of looking at the subject, most look at the screen. And that is a very different way to see. So when you look at the pictures of Cartier Bresson and wonder “How did he do that: capture someone floating in midair?”. –He paid attention! And if your attention is distracted by technology, that … can be seen in the work. Although, at the end of the day, a good picture is a good picture no matter what medium you used, digital or analogue.

I get personal pleasure from using film. So who is telling me to stop? And I cannot separate the level of creativity to this kind of tactile pleasure. You have to have a motive. Once you have technique, and with large analogue format you have to have it, it brings you to another level. It becomes that sixth sense which is so difficult to get. And I am yet to see a large body of work in digital photography that swept me off my feet and demonstrated that it could not have been done any other way.

It is interesting to find the relationship between doing things and the creative process. It is not possible to be connected without this understanding, this connection. I print commercially for other artists as well as myself, so I have to understand their take on this relationship.

Is there a way to pay attention using digital as you would using film? Could you have that level of result?

Marc Valesella: I like the example of Stephen Shore who worked all his life with an 8 x 10 format in color. Large format color film processing was very expensive, and he was very poor, so he would take only one shot on a location. Then, at some point he got commissioned to do a project in a little town Winslow, AZ, and he did it with a D100 but he said it was very important for him to turn the screen off and to take one frame only. So, he brought the old discipline with him. And that is why the later digital work is just as good as his old analogue work because it is so concentrated, it comes out of the previous form of the medium.

It reminds me of Weegee, who had just one chance per crime scene to shoot. He lived next to a police station, and had a radio on the same wave length as the police so he’d rush to a murder scene to get there before them, have just one sheet of negative and a one- time bulb—one shot! And every one of them is a masterpiece. And I think that pressure of one frame is fantastic.

Marc Valesella: Yes. And the pressure of not knowing how it will turn out. So, imagine, you go to the Mojave Desert, you spend all night there doing the exposure and trying to make it right and you just don’t know how it turned out. And it pushes you without trying. I hate being disciplined but I love self-discipline.

Which is the hardest!

Marc Valesella: Film photography does that naturally because it is not easy. That is why I think the removal of difficulty, of obstacles, is detrimental to the creative process. I recently saw some of Edward Weston small prints and I had an irresistible desire to steal them. They were just so stunning. There is also something else: that peculiar magic. It has nothing to do with nostalgia but I am yet to see a digital print that could sweep me off my feet like that. Even though I am open to that possibility. Still looking for it. Interestingly, we have taken more pictures in the last 10 years than since the dawn of photography as a medium.

But the fact that everybody is typing and publishing does not mean that there are many more Hemingways. In fact, it seems there are fewer.

Marc Valesella: Exactly. And I have a water hose in my garden, but I am not a firefighter. You know, the misconception however is that having a camera qualifies you as a photographer is silly. If you go to a music shop and you buy a flute, you just bought a flute, you know.

And of course, there is the darkroom which is the physical aspect of the print. If you have not experienced a print you have not really experienced photography. When I see a scene, I see a print.

Do you still get surprised?

Marc Valesella: Technically, I am rarely surprised. But sometimes the prints surprise me. There is an interaction in the darkroom, you know.

I heard that Henri Cartier-Bresson once went to the jungle and shot a whole series without knowing that a tiny piece of fern got stuck to the lens inside the camera. It ruined the entire footage. Has something like that ever happened to you?

Marc Valesella: No not really. But it is probably because I am an aviation engineer by training. I received a training that rules things like that out. And I also print commercially. I cannot crash customers’ negatives. And I am a bit of a fetishist about equipment. I love my motorcycle, for instance. Gaia, my wife, says I was a musician in another life. I love sound equipment, I love the beauty of the instrument.

I know a story though—for counterbalance. In 1975 Cologne Germany Keith Jarret. His piano was held at customs and could not be released before the concert. So he went looking around for a piano and finds this rickety one, completely out of tune. They tell him: we have no time to tune it. He says don’t and plays it to perfection. This concert now is a classic, if not his best. His control was so complete, both the tool (the piano) and the technique (the playing). He was so in control, he reached that osmosis. Creativity combined with his control of technique gave him this incredible power.

And yet he improvised. He had that confidence to improvise. For me part of the beauty of photography that it is simultaneously predictable and it is not. It has this element of surprise and improvisation, but you must be ready for it.

Marc Valesella: Exactly. Like Cartier-Bresson. But at least he had the range finder, whereas Weegee did not! He had to judge in split second the distance, the composition—everything. I see these days photographers who spend hours and days to get one shot and they cannot get it, while Weegee had just one, maximum two frames. And! He developed them and printed them right there and delivered the pictures to newspapers. I do not think the tools make you creative. But the tools dictate the process and the process is a multiplicator.

You’ve been printing commercially and for your own work, of course. Does technique get in the way of your creativity or has it already become the sixth sense? Do you think about it and plot it all out, do the specific steps come by themselves?

Marc Valesella: Yes, I’ve printed for Irvin Penn, Christopher Williams, (David Zwirner Gallery), Marc McKnight, black-and-white prints of William Egglestone, Helmut Newton, Walther Beckman archive, Alec Byrne and many others.

Does technique get in the way of creativity? Do you think “I shall close to this aperture and later develop it like so …” or is it automatic?

Marc Valesella: it’s automatic! I am still a techy but it is only a means, at this point, already second nature. I am always trying to learn but I do not want to end up like those “techies” that are completely obsessed with process alone, and it kills creativity, make the work dead on arrival. When all you know is technique, it becomes a trap.

I had this roommate once who studied note for note Miles Davies improvisations. What? Those guys in NY jazz clubs were drunk and high and riffing. You can’t mimic that.

In my darkroom, for 20 years, I’ve been experimenting and trying to perfect my printing. But ! you have to fulfill basic requirement. First: your print has to be sharp, edges to center—center—to corner—to corner. Then, the black has to be as black as the paper can possibly reproduce. You cannot bring me a print and claim it is “a master print” if any part of it is out of focus. And you know what, they almost all have an out of focus corner, where grains just goes to mush.

Once I printed for Irving Penn, so I worked alongside one other printer. We both worked for Irving. And one day I saw the other printer put the negative between two pieces of anti-Newton glass which reduced micro-sharpness. Irving Penn sent the print back with a question on the margin: “Did you put my negatives between two pieces of glass?”. He just knew and knew right away what the mistake was. He could have used glass to keep the negative flat to be entirely in focus but it has to be special antireflection glass. Irving knew at a glance what was wrong. But his knowledge did not get in the way of the creative process.

You must know technique to forget about it. These guys, called “techies,” who are obsessed with just the process alone, follow in the steps of great masters of photography and copy everything just so. And the work is technically perfect and utterly sterile. So you have to be really careful with that because technique can really be a trap.

Although I think, as a young person, you can’t escape it. You might even need it when you are learning your craft . And, myself, I may have done it even longer than the proverbial necessary ten years. Because twenty years I have been printing; and I am still discovering, still learning …

Essay by Lena Herzog

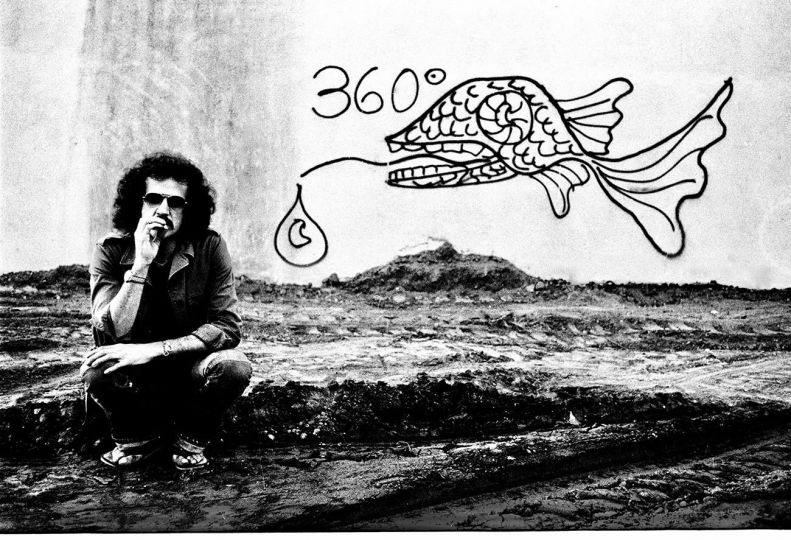

Marc Valesella, born in France in 1955, early on, developed keen interest for cameras and the photographic process.

Studied mechanical engineering in Paris but soon decided to assist fashion photographers instead.

In 1976, after seeing a Jeanloup Sieff show at Agathe Gaillard gallery, he fell in love with the art of B&W printing. Later on, Sieff taught Valesella the value of the singular print as an object in itself.

Following in the footsteps of Europeans photographers, like Depardon, Plossu, Sieff, Wender, Valesella took numerous trips to the American Southwest. In 1986 he moved to Los Angeles,where he discovered the photographers of the group f64. After developing a personal relationship with several fine art photographers as their printer, started to customize enlarging systems to achieve a higher level of sharpness, system he called Analog High Definition Printing, constantly pushing the limits of the silver photograhic print.

He showed his own photographic work in New York and Los Angeles.

Lena Herzog is a multi-media artist and the author of seven books of photography (Tauromaquia, Flamenco and Pilgrims among them). Her work appeared and has been reviewed in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Paris Review, and Harper’s among other publications and have been widely collected and exhibited in museums and institutions around the world. Her new immersive work, presented by UNESCO, Last Whispers was shown at the British Museum, Théâtre du Châtelet, among many other museums and concert halls as well as at the Venice Biennale 2022.