Nearly 30 years before President Obama shook hands with Raul Castro in the heart of old Havana, Manuello Paganelli travelled to Cuba with his cameras. He searched for his relatives—whom his family hadn’t heard from since 1953—and he took pictures. Over the years, he returned to the island nation an astonishing 60 times, making an estimated 100,000 photographs. Recently, he published Cuba: A Personal Journey, a sweeping and perceptive book collecting the best of those pictures.

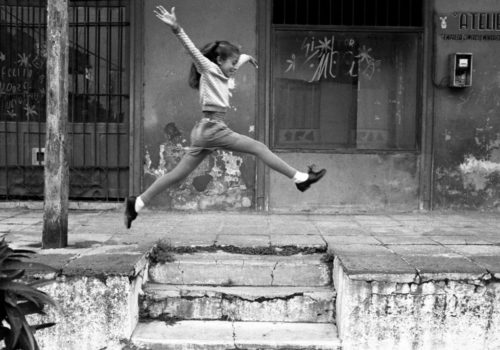

Paganelli, who is half-Cuban and half-Italian, sees beyond the now-cliché images of classic cars and cigar-rolling women, beyond the Che iconography, the peeling paint, and the other ‘easy’ pictures of Cuba. Instead, his book has more in common with Eugene Smith’s classic “Spanish Village” photo essay from 1951: the life of the streets, the wary eyes, the children, the donkeys, the long and poetic shadows. Paganelli spoke to L’Œil about his earliest trips to Cuba and the stories behind a few of his images.

What surprised me most about your book was that it’s entirely black and white. We’re so used to seeing Havana portrayed in pastel blues and greens. What was behind that decision?

On my first trip to Cuba, I packed 200 rolls of film—125 rolls of black-and-white and 75 color. From the moment I landed it was obvious to me how I’d shoot it. Cuba felt like film noir to me, like a Humphrey Bogart movie. I saw the whole thing in black and white.

Why was that?

It was like I had gone back to a time before I was born. Everything stopped in 1959. The streets, the cars, the shops. Even in the homes: Most didn’t have phones and any TV was black and white. This was 1989, but the telephone books were all from 1959. Everything was outdated and felt archival. Color didn’t feel right.

Why did you go in the first place?

When I was growing up, we didn’t talk much about the side of our family living in Cuba. But in the late ‘80s I became curious. Actually, more than curious. I became passionate about learning more about them, finding them, and hopefully helping them. The last anyone had heard from them was in a letter from 1953. It had the name of a town and a couple of clues. This was 35 years later but I had to try.

What was that first trip like?

I had no idea what I was going to see because I didn’t know anyone who had been there. People forget, but at that time it was a forbidden land. There were some Spaniards and South Americans there, but nobody was going around taking pictures. I was almost always the first tourist and definitely the first American they’d seen. I was very strange in the eyes of the locals.

In those early days, were the locals receptive to having their picture taken?

I went there as a tourist not a journalist so that my access wouldn’t be controlled, but the locals were still hesitant, on guard, and I didn’t want to get them in trouble. I would approach them and they would look around for cops or neighbors or undercover types. But there was never a problem. They wanted to know more about the US, what we did, what we thought of Cuba. One of the photographs in the book, from my first or second trip, captures the Cubans’ mixed feelings about my taking pictures: The white guy is happy to be photographed but the guy with the cigar is suspicious, like, who is that guy?

Did you simply wander the streets? Did you have a shoot list?

I just walk. I’m able to see things fast and capture what my eyes show me. I don’t have any sense of direction—I’m always lost—but that takes me off the beaten path and I always discover something I’m not expecting.

The photograph of the hair salon is . . . haunting. The metal hair dryers gleam but the seats are tattered.

That was from the early 90s. I walked in and immediately the scene took me back to when I was a little boy, when my aunt and mom brought me along to the beauty shop. But this picture was made during the Special Period, after the Russians left, and the salon was empty. No one could afford this kind of luxury. At that time, there was not much money in Cuba, and the markets and shops were empty. Before the Russians left, Cubans were better off than most people in Central America. They had great medical care and education. It was a different after. And the Cubans who fled to Miami on rickety boats? It was not so much that they couldn’t stand communism; they just wanted a better life.

You made a picture of Gregorio Fuentes, who you believe was one of Hemingway’s inspirations for The Old Man and the Sea. How did you find him?

A waiter in a restaurant told me that his uncle occasionally cooked for Hemingway and mentioned Gregorio. So a friend and I drove out to Cojimar, the tiny fishing village where he was said to live. He was 95 at that point and fragile, but we talked for hours. He told me he first met Hemingway in the ‘30s and showed us letters Hemingway had sent him. When it came time to take his picture, I was so emotional. I shot a couple of rolls but only a few frames turned out because I had tears in my eyes.

There are pictures in this book that remind me of the work of the some of the great LIFE photographers—Gordon Parks’ pictures in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, Eugene Smith’s Spanish Village. Which photographers influenced you?

I’m actually self-taught. I was planning to go to medical school and photography came to me after college. I read something about Ansel Adams. I was taken with his work but I didn’t know who he was. I got his number from information and called him. We became friends during the last two years of his life, and he was definitely my biggest influence.

Many of the books about Cuba are filled with pictures of classic Fords and old women smoking cigars. But you bring us inside a funeral, to the bed where a mother is nursing her child—moments of extreme intimacy.

My background has been as a documentary photographer, so it’s important for me to capture authentic moments in daily life.

During the 60 trips you made to Cuba, how many pictures did you take?

Oh, God. I have binders and binders full of negatives. I’d say probably 100,000.

How did you get from 100,000 to the 115 in the book?

I asked Jim Colton, the former director of photography at Newsweek and the former photography editor at Sports Illustrated, for his help. I’d met him in late ‘80s and I couldn’t have done this book without him. In fact, he chose the cover image.

That photograph shows two young children, holding each other, on a slender dock as clouds gather in the distance.

My entire reason for going to Cuba was to find my family, and I found them on my third or fourth trip. This image is of my family, my blood. My niece, who is close to 30 now, is protecting her brother. I love this image because of the symbolism: You see a cross, and you see the girl looking sideways, like Mary, protecting the citizens of Cuba. I spotted them on the dock in their best clothes and I knew it was about to storm. So I ran to get my Hasselblad. I was loading the film as I was running back to the dock. I shot a five, six frames with no tripod and then the rain came like a waterfall.

Are you still in contact with your family in Cuba?

Of course! In fact, I lead photo trips to Cuba and one of my nephews, who was maybe two or three when I first met him, is now my right-hand man on the ground.

Is there a single image that represents the book’s overall message?

Yes, and it’s the book’s final picture, a tight shot of black hands holding a white dove. That was taken very early, on my first or second trip. I remember it had rained all night, terrible rain, and we couldn’t drive because the roads didn’t have lights and there were potholes as big as the car. So we spent the night in a small town, La Florida. The next morning, I woke up at sunrise and started wandering around. From far away, I saw these two black Cubans walking toward me. One of them didn’t have a shirt and I saw something flash white. It caught my eye. He was holding a white dove.

One of those moments. . .

. . .Yes, and so many things were coming to mind. I was thinking of Picasso’s picture of the hands and dove, and of the symbolism of the dove. I remember thinking, “Who decides what freedom is?” People in Cuba thought of themselves as free but people in Miami didn’t see it that way. And there’s another layer: I started talking to the guy who was holding the dove and he said that he might keep it or it might be his meal. Again, this was during the Special Period when food was scarce. And you know, Picasso never had to worry about his next meal. So for me this picture—and this book—is about trying to show a side of Cuba that very few people had the opportunity to see, to show the misconceptions as well as the truths.

Interview by Bill Shapiro

Bill Shapiro is the former Editor-in-Chief of LIFE magazine; on Instagram, he is @billshapiro.

Manuello Paganelli leads photography workshops to Cuba; information is available on his website. More photos can be seen on his Facebook page.

Manuello Paganelli, Cuba: A Personal Journey 1989-2016

Published by Daylight Books

$60.00 US