“On March 11, 2011, an enormous earthquake hit northeast Japan. The subsequent tsunami forced 400,000 people to flee their homes and resulted in the loss of 16,000 lives, in addition to 4,000 who remain missing. A nuclear crisis still threatens the security of millions of people.” – Voices from Japan

Opening this week, After the Water Receded: Images From Japan, an exhibition of photographs by Magdalena Solé taken in the Tohoku region of Japan where the Tsunami occurred. Solé, a New York City based photographer, was born in Spain during the Franco dictatorship. No stranger to transition, her family left for Switzerland when she was seven, where she grew up through college. Profoundly effected by her experiences photographing in the hardest hit region of Japan, she returned several times despite the publication of her book, “New Delta Rising” (University Press of Mississippi) based on her longtime work in the Mississippi Delta, during this same period.

I spoke with Solé about her experiences documenting both regions.

What motivated you to photograph in Japan after the Tsunami?

Since I first visited Japan in 1991, it has become my spiritual home. I have traveled and photographed there many times. Before the Tohoku disaster, I photographed in southern Osaka in a tiny area called Kamagasaki. During Japan’s economic boom years the district attracted men from all over Japan looking for construction jobs and a way to remake themselves. Today, Kamagasaki, feared by the rest of Japan, is an area for the unemployed and homeless, virtually all of them male mostly in their 60s. Though shunned, they project the core values and vitality of a polite, respectful, highly organized Japanese society.

I was deeply saddened by the vast human tragedy caused by the Tsunami, Earthquake and Nuclear Fallout. Part of my interest in the Tsunami area was to bear witness to the disaster, and add whatever support I could.

When I went to the Tohoku region after the disaster I realized that the people were immensely grateful to be visited and remembered. People arrived from all over Japan to help and volunteer their time. I was moved by the solace to be found in the midst of such tragedy. The resilience of the Japanese is a great teaching to me.

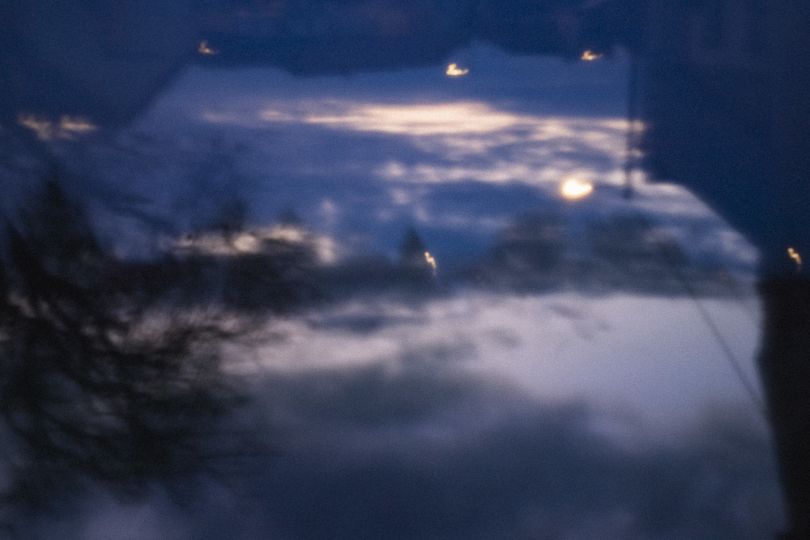

The immediate contaminated area around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is called Futaba District of Fukushima Prefecture. The mayor of Tomioka town issued a special permit for my visit. I was a little worried about my own contamination as it really wasn’t clear how much there was. A common conceit of apocalyptic films is the emptiness and quiet as the protagonists explore the ruins. Such was my expectation when driving through the evacuated zone around the crippled reactors – that is until I saw an ostrich on the road I was driving. Had it been a Brontosaurus I couldn’t have been more shocked. The ostrich, a former farm animal in the region, opened my eyes to the variety of life that remained and thrived. Pigs, cows, and dogs all returned to their feral state and were doing quite well. Life was everywhere, just not human life.

Other than Native Americans, America is a country of immigrants. Our ancestors left somewhere to find and build a new life. We all have a restless gene.

The Japanese on the other hand treasure continuity, a business that is 800 years old, or a family craft that can be traced back 10 generations. It is not unusual for a family to even adopt a talented apprentice so that a tradition can be continued. Farmers are no different. Their land tilled for generations is as important to them as the art of a sword maker. You move to new land and all of your tradition and heritage begins anew, all that came before vanishes. Your cultural slate is wiped clean. Farmers evacuated lost all that defined them and their families; farmers who continued on their land found they could no longer sell produce, milk or meat which the public thought was contaminated and had to decide whether to abandon their land and their heritage. For people without that restless gene this is the most painful and profound of decisions.

For most of us destruction by natural disaster is experienced through a TV. When you are present the experience is vastly different. It recruits all of your senses. You can touch debris, smell the rot and decay, see the great swath of land touched by destruction and experience a loneliness standing in empty destroyed formerly inhabited space that cannot be relieved by changing channels. All of this adheres to your soul.

Is there any connection with your experiences in Japan vs. your long-time work in the Mississippi Delta?

People who have seen my photographs of the Tsunami area and the Mississippi Delta always show great surprise and say, “Gee, it must be like night and day photographing in Japan and the Delta”. Actually, the experiences were remarkably similar.

I expected people in the Delta to be suspicious and distant of outsiders and the Japanese to be in shock from their losses with little interest in outsiders exploring their suffering. I was wrong on both counts. Separated by 12,000 miles and a vast cultural divide the people of the Delta and Japanese survivors were open, freely sharing their stories and what little material means they had. Each culture certainly revealed unique customs, but the core of each was an embracing warmth that was almost disorienting given its context. I was ashamed of my usual urban selfishness.

Your book “New Delta Rising” was recently published by University Press of Mississippi with images shot in the American South. How did that come about?

The Dreyfus Health Foundation was sponsoring a rally in Cleveland, Mississippi and I got myself invited. All I knew about the Delta was from hearsay and the Blues. After a week I was in love. That was the first of thirteen trips over two years that included 10,000 miles of criss-crossing the Delta in a car.

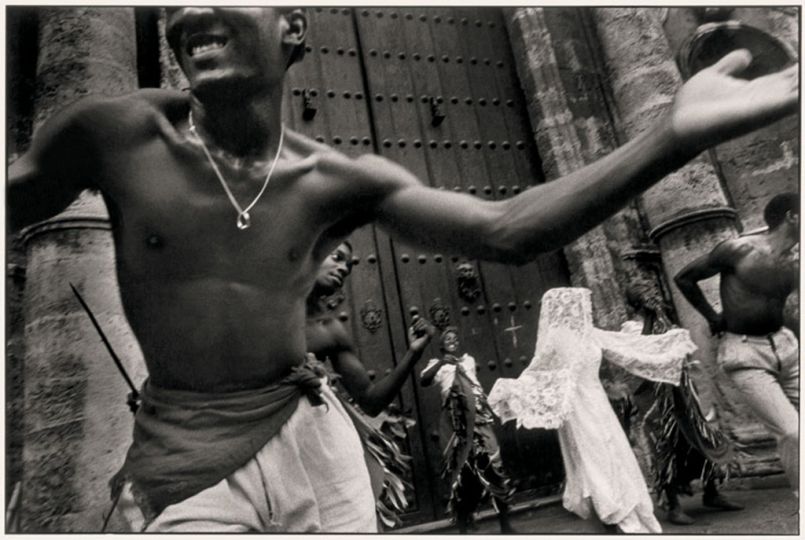

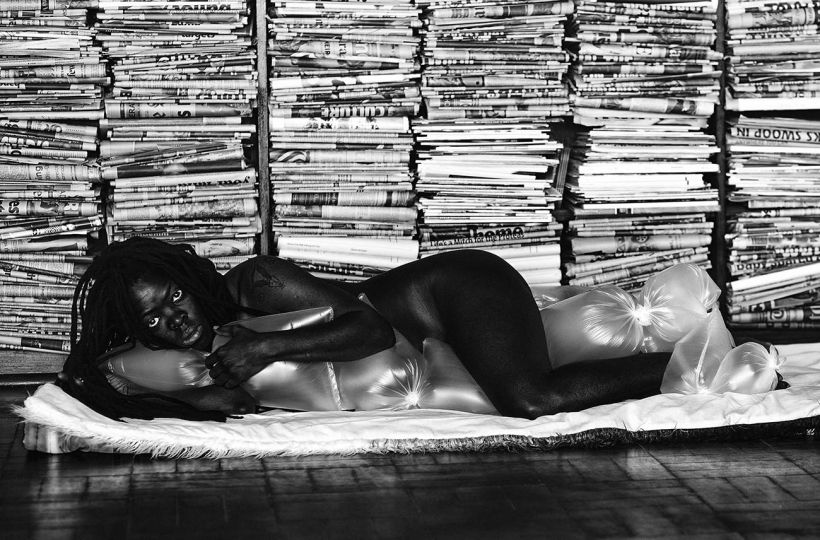

“New Delta Rising” is an exploration of communities in the Mississippi Delta, an iconic region lying between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers, running from Memphis, TN to Vicksburg, MS. The Delta evokes visions of sharecroppers, plantations and, the sound of the Blues. The area has a small wealthy gentry and a large impoverished underclass living in dilapidated houses and tilting trailers. It is one of the poorest places in the United States with the saddest infant mortality rate, and rampant unemployment. What is little known is the warmth, resilience, community and family cohesiveness of its people.

People in the Delta were for the most part surprised that I was interested in them, but I genuinely liked the people I met, and the different lives I encountered. I shared their laughs and their tears. I never met anyone who didn’t like having their picture taken with the exception of women when they worried that their hair wasn’t right. Whenever possible I visited the people again and again, and also brought them their photographs. Just last week I returned to the Delta to bring them “their” book. It was such an immensely joyous journey.

Elizabeth Avedon

Exhibit

After The Water Receded: Images From Japan

Photographs by Magdalena Sole

Also showing: Portraits of Survivors by Naoto Nakagawa

Co-curators: Sandra Kraskin and Elizabeth Avedon

Sidney Mishkin Gallery, New York April 20 – May 18, 2012

Book

New Delta Rising (University Press of Mississippi)