Ruddy Roye is a Brooklyn based portrait and documentary photographer. Roye was born in Montego Bay, Jamaica, and studied English Literature at Goucher College.

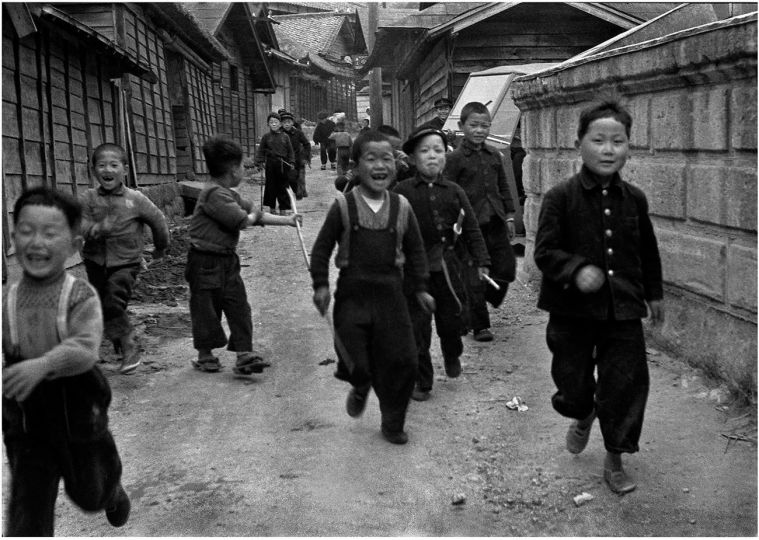

Roye uses his camera as a tool that allows him to document the world around him as he sees it. The images he produces speak of the human condition, addressing the myriad instances of suffering and injustice he is witness to that are often overlooked. Yet the images he produces of events such as the Hurricane Katrina aftermath, The Black Lives Matter movement, chronic homelessness, and his own personal project When Living is A Protest, do not merely exist to capture misery, but also to convey resilience and compassion. Roye’s portraits are frequently produced as collaboration with the people he photographs in tandem with text that further humanizes them and evades their exploitation.

David Holloway: I’ve been fortunate to be with you out on the street and I’ve seen you photographing. Everything you do, is done with intention, while at the same time it’s very natural. When you see a subject, there is an unspoken conversation, maybe eye contact, or a gesture, which leads to you starting a dialog. I’ve never seen you photograph someone without engaging them in conversation. Then I’ve never seen anyone refuse to let you photograph them, regardless of their situation. If anything, they always seem to be grateful for you having taken the time to stop them. Then looking through your take, It seems every image is razor sharp and deliberate. I’ve heard you described as a sort of antithesis to street photographer Bruce Gilden. How did you develop your process, or have you always worked this way?

Ruddy Roye : I believe that my “process” as you put it developed over time. On one hand it was my need to change the narrative that has always been forced on BLACK images coupled with the fact that whatever was happening to black folk was also happening to me. Photographing the way I do came from a personal space. I figured out that if I spent time trying to change the world I live in, I could create a better one for my boys.

DH: Instagram is thick with accounts of pretty young girls, whose feeds full of self-portraits and toes in bathtubs lead to thousands of followers. You’ve managed to develop a remarkable following by making very thoughtful, respectful images. Why do you think your work is so popular in social media?

RR : I don’t really think I am popular. I believe that there are a few people who genuinely live their lives the way I feel and think and as a result my work resonates with them. Being popular I think denotes a kind of conformists attitude towards engaging. I don’t think the two go together. My work is different yes, it seeks to engage all peoples but I believe that I manage to only reach the proverbial choir. The masses still prefer to look at pretty young girls and their self portraits while sitting in bath tubs urging their millions of followers to go like their new buttocks image.

DH : You might be as good a writer as you are a photographer. You also might have the longest captions on Instagram. I tend to fly through posts on Instagram, liking this one or that, then following another hashtag to a different subject, making a witty comment or being snide, but when one of your posts pops up in my feed, I instinctively switch to gears to slow down and take it all in. Do you think your message comes through without the text? How important is the writing to you?

RR : I don’t believe that my images can live fully without their texts. In a way the texts protect the authenticity of the image. In a way the texts prevent the image from being shrouded and trapped in the ever so often stereotypes that have always followed the black image. Writing covers the nakedness of the images.

DH: A lot of the work that has helped people recognize you is made in your neighborhood in Bed-Stuy, a neighborhood that is quickly becoming the gentrifying face of Brooklyn. When you photograph there, is the work about race? What sort of expectations do you have for your non-black audience? I am talking about white people, but not just white people, what do you expect viewers in Japan or anywhere else to take away from experiencing your work?

RR : Wow — great question.

The image is less about race but more about looking at how a group of people live or are being displaced in Bed-Stuy. I believe that if that same group was white I would still be taking pictures because I am essentially photographing the pallette that is before me.

That said, it so happen that this particular group of folks is Black. Through the image I want to show the injustice of gentrification. But I don’t want people to think that I believe that Gentrification is all bad. For me coming into a community and not caring about the people that you came and found is endemic of a larger problem. I use photography to dig deeper into what that thing might be. Is it that people are essentially selfish, and heartless. Or is it more a case of survival of the fittest?

DH: You’ve been doing this for a long time and you’re just now starting to be recognized on a larger scale; you’ve landed your first National Geographic assignment and you’re speaking at Look3. Where do you see the limits of your own work? Do you see yourself continuing to work in the same manner, or is there an evolution in your process?

RR: I would like to continue doing this work but evolve to photographing slower using the analogue process, but also doing a bit of video to compensate where photography fails. I like to challenge myself and so I can see myself growing with both the old and the new, hoping to deconstruct and change the narrative of the Black Image in America.

© 2016 South x Southeast photomagazine sxsemagazine.com

FESTIVAL

LOOK3

• Artist’s Talk: Ruddy Roye

Friday, June 17, 2016 at 11:00am

The Paramount Theater

215 East Main Street

Charlottesville, VA 22902

United States

• Exhibition: When Living is a Protest

June 13 – 19

The Bridge PAI

209 Monticello Road

Charlottesville, VA 22902

United States

http://look3.org

About the author : David S. Holloway was born in 1971 in Enid, Oklahoma. Before receiving his B.A. in journalism from Arkansas Tech University in 1996, he interned as a photographer/journalist on assigned events for The Express and Mwananchi newspapers in Tanzania. While covering the preparations for that nation’s first multiparty elections, Holloway served as stringer for the Nairobi bureau of the Associated Press. Holloway became a staff photographer for The Times Record, Arkansas, in 1997, before moving to Virginia to work as a general-assignment photographer with Times Community Newspapers and Media General. Since 2001, he has been a freelance photographer for musicians, advertising agencies and various publications, including TIME, Newsweek, LIFE and Rolling Stone. In 2004, the White House News Photographers’ Association (WHNPA) awarded Holloway Second Place in their “Eyes of History” Still Photography Contest for his portrait of Dr. Jane Goodall, taken at the Jane Goodall Institute in Silver Spring, Maryland. In 2005, the WHNPA again awarded him Second Place in Domestic News for “Protester Kiss,” taken during the final night of protests at the Republican National Convention.