Artist, Binh Danh follows his own path. He thinks deeply about our collective history, our present and future. At the 2016 LOOK3 Festival of the Photograph Binh will present his latest work comprising daguerreotype photographs of the American landscape. The following interview serves as a modest entry into Binh’s newest artwork and his presentation at LOOK3.

Matthew Rond: The title of your artist talk at LOOK3 is “Reflection in the National Park.” What does this title tell us about your latest work?

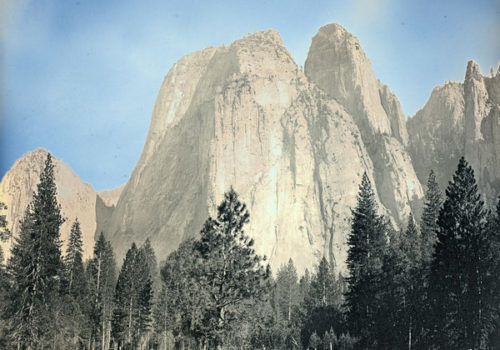

Binh Danh: My latest work is done with the daguerreotype process, which produces a photograph on a silver plate. The photograph itself is reflective due to the mirrored surface of the silver plate. The idea is to have the viewer’s face reflect in these iconic National Park scenes while they are experiencing the daguerreotype, becoming part of the American landscape. Perhaps in that moment of seeing yourself in the actual photograph, you could contemplate your relationship to the United States, its majestic landscape, and democratic values.

MR: How does this new series of photographs relate to your previous artworks? And how are they different?

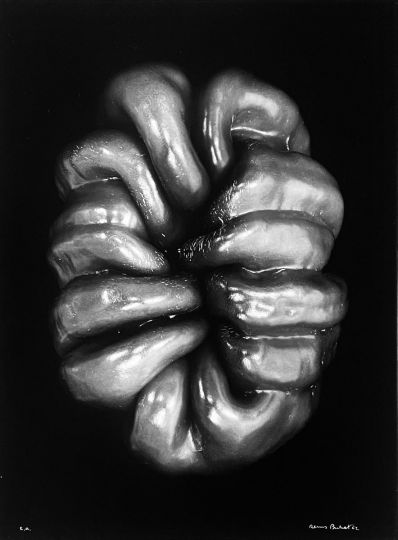

BD: Regarding the processes, when compared to my current works on daguerreotype to chlorophyll prints, the medium is different. The past work is a photographic image on a leaf; the recent is on a silver plate called daguerreotype, a 19th century technology. At the same time, both processes have a linage to the invention of photography. The daguerreotype process is a 19th century process, being the first photographic process that had a commercial venture. The chlorophyll print is dated to John Herschel’s 1842 anthotype process, where plants and fruits are ground up to produce a light-sensitive pigment that coats a paper surface. With both processes, it’s not possible to make an exact edition of prints, challenging the notion of what photograph has become since its invention.

Regarding concept or genre of photography, I find my new series of photographs related to my previous artworks as both being about landscape photography. They are about the land and the history the landscape holds. Both works are about our relationship to landscape and history. Of course the locales are different, but also it’s the spreading of United States imperialism in what became the National Parks.

MR: You’re photographing geographically disparate locales within the United States as part of your current landscape series – Yosemite and other national parks. And American Civil War sites in the South? How do these places connect to one another for you?

BD: This is a great question. First the American Civil War sites are part of the National Park Service and an extension of my National Park series. The National Park Service network also contains historical sites, such as Manzanar National Historic Site, where Japanese Nationals and Japanese Americans were imprisoned during World War II. Also the connection is historical for me. After the American Civil War, many landscape photographers working for the Mathew Brady studio began publishing photographs of war and for the first time the public was able to see the carnage of a nation divided. But it was not well received; the public didn’t want to face the reality of war photography. War was supposed to be heroic, like in the large academic paintings depicting war in action. But then a different type of landscape photographs began circulating from photographers in the West by photographers like Carleton Watkins or Eadweard Muybridge, and the many others photographing in the Yosemite Groves in California. These photographs, as well as many other factors, sparked President Abraham Lincoln in 1864 to sign legislation giving Yosemite Valley and the nearby Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the state of California “upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort and recreation.” This set the stage for the creation of the National Park Service.

MR: Knowing how much the US war with Vietnam has meant to your artistic practice, I’m curious to know how the American Civil War relates for you. Do you see these wars as connected? Is your interest in the American Civil War different in some way to that which you had with the US war in Vietnam?

BD: I do see these wars connected as in North and South fighting each other. The Vietnam War, also known as the American War from the Vietnamese perspective, was a civil war, Vietnam a country divided will not stand (a reference to the Abraham Lincoln quote, “a nation divided would not stand”). At the same time, the American involvement in Vietnam was to stop the spread of communism, standing up for a weaker South Vietnamese government being invaded by the Viet Cong. The United States government did not view the War in Vietnam as a Civil War to justify their action. There are those who question that the American Civil War was a war about the validity of slavery versus states’ rights. I found my interest is the same in dealing with both wars. I am interested in history and the consequences of war, the trauma that continues to live on, even today when dealing with the American Civil War. I am interested in the stories of the soldiers and civilians in a war rather than the generals and tactics that often get highlighted when discussing warfare. What are the items that were left out of the history books?

MR: You’ve traveled back to Vietnam and to Cambodia and visited sites where the Khmer Rouge killed thousands of people, sites that are now memorials and museums. American Civil War sites are similarly set up as protected places and memorials. The same could be said for our national parks. Is memorializing these places important to you and this current body of photographs?

BD: Yes, I found these sites as living museums. What a photograph does best is capture that place in that moment. That for me is memorializing those sites.

Making photographs is a way for me to engage in these sites and sights. I know not everyone could visit them, so I hoped I could bring these sites to them in my artwork.

MR: Your previous artwork placed importance on the image and the object, the medium being an important part of the message. Does the daguerreotype as object carry specific importance in this latest series? If so, how?

BD: Since my daguerreotypes are quite large, they have to be framed and hung on a wall. In a way they lose their object likeness when compared to 19th century cased daguerreotypes where the object is meant to be held in the viewers’ hands. But many 19th century qualities still exist in my modern day daguerreotypes, such as reflection; the image constantly changes depending on the angle of viewing, and the high resolution is still there. Also given that my daguerreotypes, like the 19th century ones, are one-of-a-kind, they are true objects since only one exists. I like how this challenges today’s notion of photography, where many photographs made with digital cameras are rarely printed and only exist as images on screens and not a photograph, which for me is an object in the here and now. My usage of the daguerreotype is to pay homage to the history of photography, making it a “21st century” medium since people today rarely encounter daguerreotypes.

MR: Will you be using researched and found photographic materials in conjunction with the daguerreotype images you’re making? How might those merge?

BD: Yes, I do merge researched and found photographic materials in my gallery installation. I use the gallery as a presentation of my research. I always consider my work “landscape as research.” Rather than write a history book or make a documentary film, I stage a gallery installation as my creative output.

©2016 South x Southeast Photomagazine, sxsemagazine.

FESTIVAL

LOOK3

• Artist Talk: Binh Danh

Friday, June 17, 2016 11:00am 1:00pm

The Paramount Theater

215 West Main Street

Charlottesville, VA, 22902

United States

• Exhibition: Binh Danh, Reflection in the National Park

June 13 – 19th, 2016

111 E Main Street

Charlottesville, VA 22902

United States

About the author : Matthew Rond is a photographer and photo editor living in Atlanta, GA. He holds a BFA in photography from The Atlanta College of Art, the oldest private art college in the South before being purchase by SCAD. Matthew was a founding member and contributing editor for the CNN Photos blog and is employed at Turner where he produces photos that promote programming across their networks. Matthew’s work as a photographer focuses on the people and landscape of the urban American South.