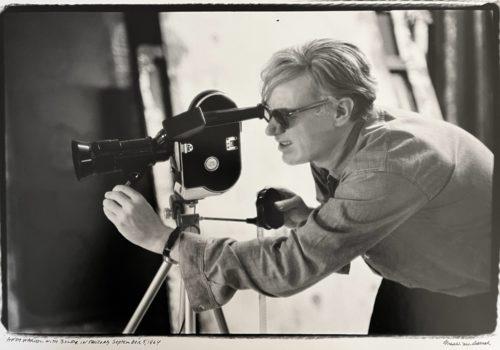

Life magazine gave me the assignment to do “The Cats of Africa.” I had photographed some animals before, though I certainly wasn’t a cat expert, but I could hire people who knew things. They’d lined up a hunter in Botswana, who was a hunter for zoos.

He had caught a leopard, and he put the leopard in the back of the truck, and we went out into the desert. He would release the leopard, and most of the time the leopard would chase the baboons and they would run off and climb trees. I had photographed all this. But for some reason one baboon didn’t get off. It turned and faced the leopard, and the leopard killed it. We didn’t know that this was going to happen. I just turned on the camera motor, and I got this terrific shot of this confrontation.

There was a different feeling about that in the 1960s. We were always setting up pictures of some sort. I think they probably still do it now. But now there are many, many more competent photographers doing this stuff over long periods of time—four or five years if a scientist is on a big study. They’re getting good stuff without helping the picture. But no one was working that way then. Scientists couldn’t handle the crude cameras that we had well enough to get good stuff. I felt that my job was to get the pictures. I learned how to bait animals and do things from the experts in Africa. We shot a gazelle and put it in a tree and waited for a cat to come. I didn’t feel bad about it at all. It sounds terrible now, I know, and maybe my attitude would be different now. But it wasn’t then, and I don’t know what more to say. I’ve been criticized a lot. But to me, I had to do what I did.

(Interviewed on October 27, 1993. Excerpted from: John Loengard, LIFE Photographers: What They Saw, Boston, A Bullfinch Press Book, 1998)