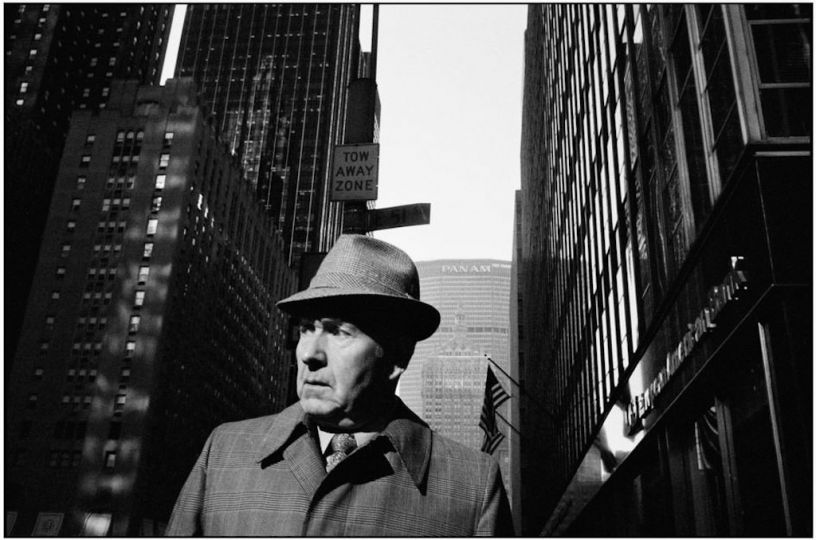

Raymond Depardon goes out to meet French people to hear what they have to say. From Charleville-Mézières to Nice, from Sète to Cherbourg, he invites people he encounters in the street to talk freely in front of the camera.

It must be noted from the start that Les Habitants is a rather touchy topic. It took me several days after the screening before I decided to write about it, given that the subject in question must be handled with care, like a vial of nitroglycerine.

Desproges once said, “You can make fun of anything but not in front of just anybody.” Similarly, one can certainly show anything, but not to everybody. The film credits cite Depardon as the author, which suggests a positive, humanist, compassionate bias. But if the film were credited to Marine Le Pen, the perception of the film would have been much different: like the chilling effect of Lev Kuleshov films.

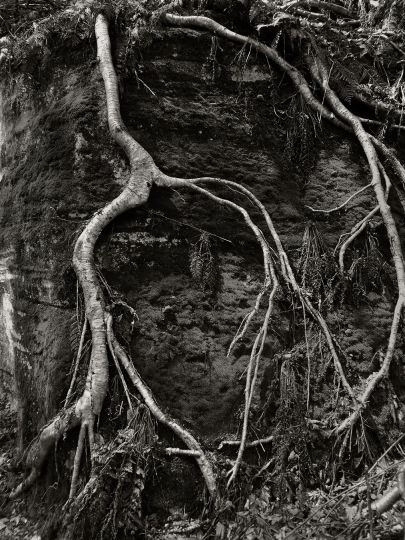

Depardon traveled around France with his crew, and for months filmed hundreds of conversations; and what did he preserve as worthy of showing as a representative sample of the French? People down on their luck, divorcés, the poor, alcoholics, battered women, the unemployed, a small-time dealer who sends shivers through his mother’s spine, a young woman on welfare working in a strip-club, sex-crazed youngsters who keep count of the girls they hook up with, two gullible girl-friends recently converted to Islam, and in the middle of all this, old-timers the world has left behind and two biddies from Nice ecstatic about their lives as retirees. On the whole, the movie produces a shock bordering on nausea, as hardly anyone speaks French anymore; instead, they use some street newspeak stripped of grammar and basic vocabulary, all in order to evoke situations so depressing that the viewer immediately feels super privileged. This may well be an accurate reflection of France, the reality we refuse to see and are never shown. A bitter, violent, ghastly glimpse. We feel sorry for these people all the way through; we wonder what is this crumbling, drifting society with no hope and no illusions. We are well aware that Depardon wanted to probe the very depths of France, hit the very bottom, as Raffarin used to say. But the feeling of waste, the wallowing in misery that pervades the film makes us feel like we’re being subjected to an hour and 24 minutes of Brèves de comptoir,* except that everybody’s sober, which is much more disturbing. Where are people who are flourishing (besides the young woman of North African origin who did well at school but whom her veiled mother wanted to marry off as soon as possible); where is joy, lightheartedness, love (besides the final sequence)?

Depardon made a deliberate choice and wanted to show a culturally mixed France (much more than it really is), stammering in broken French, in a quotidian struggle with everyday adversity, on the brink of collapse. One cannot but see it as a histology of an ailing country, gnawed away from the inside, and for better or worse fighting to survive. By comparison, Ken Loach and the Dardenne brothers appear almost bourgeois. Depardon’s choice is an uppercut to anyone reasonably well off. What should we think of that France? Should we look at it with compassion, disgust, anger? All three? Undoubtedly despite himself, Depardon offers a portrait of France’s “inhabitants” (rather than of French people, please note the difference) that makes the Front National rub their hands with glee.

In his earlier project, La France, we could already clearly sense the nostalgia for a picture-perfect France that is all but gone. Les Habitants throws the door open to the most reactionary politics that will take his film as an objective proof (after all, it is a documentary) of the decline of modern society and a vivid demonstration of the failure of the social-democratic model, such as the integration policies promoted by successive governments. To that end, the choices made by Depardon are quite dangerous if he deliberately discarded the healthy to show only the sick, privileging exotic types and puking characters, over simple, ordinary individuals. And even if he is objective (which I doubt, although he firmly believes this is the case), a question must nevertheless be raised of his responsibility as witness. Who benefits from these images? Who is going to use them? Perhaps Depardon doesn’t care. In a film whose very form is a cinematic transposition of the French proverb, “The dogs bark but the caravan goes on,” one has to wonder: has Depardon abandoned the ship of France to film its wreckage or does he see himself as the captain going under with his beloved vessel?

* Brèves de comptoir is a series of books published in 1988 by Jean-Marie Gourio as well as an eponymous 2014 film directed by Jean-Michel Ribes, based on bar humor and colloquialisms. — Trans.

FILM

Les Habitants

Raymond Depardon

Sortie le 27 avril 2016

http://www.leshabitants-lefilm.com