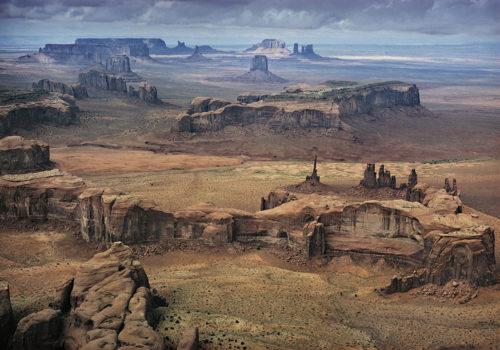

On the occasion of the publication of the book The American West, Les Douches la Galerie presents its fourth personal exhibition of Ernst Haas. Taken between 1952 and 1981, the thirty-two photographs presented testify to his sensitive explorations of the American West and the wide technical palette that characterizes his work.

In the summer of 1952, Ernst Haas, an Austrian-American photographer, set off on a journey to the heart of the American West. Commissioned by Life magazine, he hitchhiked along the deserted roads of New Mexico, in search of these mythical landscapes that had fascinated him as a child. (…) For the magazine, this journey led to a three-double-page essay titled “Land of Enchantment: A Hitchhiker with a Camera Records New Mexico’s Many Moods”, with photographs that were only the beginnings of a larger work on the American West 1. It showed large expanses of sky above a road lined with telegraph poles fading into the dust in the distance, and in another image, an Indian woman photographed close up on the left of the frame, a child and a second woman carrying a baby, subtle triangular composition guiding the gaze towards the pueblo in the background – themes heralding Ernst Haas’s infatuation with the myths and realities of the American West, a true passion that he would keep for the next thirty-four years. In addition, according to Inge Bondi, this trip also allowed him to develop another theme that was to mark the rest of his professional career – how to apprehend the world through color: “By photographing in black and white the desert of New Mexico, he felt a great need for color. This is how he began his life’s work on the uses and meaning of color in photography. 2»

Ernst Haas had arrived in the United States in 1950 at the invitation of Robert Capa, who had appointed him vice-president of Magnum Photos, the prestigious photography agency of which Haas had become a member a year earlier. His decision to join Magnum corresponded to a desire to maintain a certain independence from the editorial world, just as he had, in 1949, refused a job offer as a staff photographer at Life magazine, explaining in writing that ‘“There are two kinds of photographers – those who take pictures for a magazine to make money, and those who make money from taking pictures that motivate them. […] What I want is to remain free, to carry out my ideas. […] I don’t think there are many editors out there capable of giving me the assignments I give myself. 3» (…)

For Haas, going to the United States meant opening new creative doors, in addition to business opportunities: “With hindsight, I think my transition to color had something psychological about it. I will always remember the war years, as well as the five years of deprivation that followed, as years in black and white, I would even say gray years. So that was the end of the grayness. As in spring, when everything is reborn, I wanted to celebrate this new period, overflowing with hope, with color. 4» (…)

Ernst Haas had a perfect mastery of the peculiarities of Kodachrome. Because color film is not forgiving, and the exposure must be perfect at the time of shooting – no retouching is possible afterwards. From the outset, Haas was able to dominate the demands of this tool, as his archives at Getty show, with countless rows of perfectly exposed images. (…) In his work on the rock walls and their infinite variations on the same color, he knew how to play on the subtle gradations of tones, while preserving an impression of depth and movement in the frame. (…)

One of the pioneers of the diapositive, Haas had understood that his ability to use color for aesthetic as well as symbolic purposes was highly sought after: he knew how to take advantage of it to obtain assignments that allowed him to continue his exploration of nature in the United States. (…)

He says for example: “When a shoot takes place in remote areas, there is a lot of waiting between takes, and I have always taken advantage of this wait to enrich my collection of images of natural phenomena5. It is indeed on film sets that Ernst Haas produced his most beautiful photos, and particularly during the filming of Little Big Man with Dustin Hoffman, where the meticulous reconstruction of the life of the American Indians allowed him to transport the viewer in the nineteenth century. (…) Thanks to Little Big Man, he had the opportunity to deepen his ties with the American Indians, in whom he had already been interested for several years and whom he had amply photographed for a dossier published in 1970 in Life magazine, entitled “America’s Indians, a Conquered People Wake Up”. (…) Obviously, Haas felt a very strong connection with their philosophy and their way of life: “In this region of mesas and adobe houses, I slept under the stars with the Indians, I looked at the world from their point of view, had philosophical discussions under tepees and felt a great affinity6. However, he was acutely aware of the sabotage, destruction and endangerment of their culture and way of life by white dominance in the West. (…)

Despite his reservations about the banality of advertising and its deleterious impact on the landscape, Ernst Haas undeniably had tenuous ties to the commercial world, as shown by his contribution to one of the world’s most famous and effective advertising campaigns. It was in 1972 that he began his work for the “Marlboro Man”, and he continued it steadily over the campaigns until his death in 1986. (…) Haas’ style lent itself perfectly to these advertisements , for he had no equal in capturing the movement and energy of riders against a backdrop of wild landscapes – those great plains and mountains of the West that he knew so well. (…)

Ernst Haas was aware of his place in the photographic tradition of the American West: in 1976 he made a pilgrimage to Big Sur and Point Lobos in the footsteps of Edward Weston, claiming to have been “very inspired by his work”, wishing “to pay homage7” to the man who had “taught him to electrify a motionless image to make it move8. Ernst Haas in turn influenced a new generation of photographers interested in a use of color that was both creative and meaningful, who were not satisfied with only the appeal of chromaticism. (…)

Haas thought of himself as a poet with a camera, and his extensive exploration of the American West perfectly demonstrated his willingness to infuse his knowledge and sensitivity into his work using all the visual strategies at his disposal, and seeking innovative ways to portray the world through the lens of his camera. Through the profusion of his writings and interviews on the nature of the photographic medium, Ernst Haas established himself as a true thinker of photographic communication. In his philosophy, the characteristic visual signature of a photographer must come from within. He summed up his thoughts as follows: “There is no magic formula for finding your style, but there is a key. Style is an extension of personality. It is the synthesis of this indefinable whole – the feeling, the knowledge and the experience. Consider the color as a set of links that are woven inside the frame. Don’t over-analyze your results! Never try to find your own secret in the one you admire. No need to try to catch soap bubbles: we watch them float in the air, we rejoice in their changing existence. The thinner they are, the richer their color palette. Color is joy. And joy cannot be thought about. 9»

Paul Lowe

Excerpts from the introduction to Ernst Haas: The American West, Prestel, 2O22

1 The text of the article presented Haas as “an exceptional Viennese photographer […] who considered himself a philosopher who takes pictures”, explaining that he had “hitchhiked the road networks of white man, visited the pueblos of the redskins” and described “the drama, the loneliness and the immensity of the country”. Ernst Haas (photo), “Land of Enchantment: A Hitchhiker with a Camera Records New Mexico’s Many Moods”, Life, September 15, 1952, p. 117.

2 Inge Bondi, “Biographical Essay”, 2000, Ernst Haas Estate, https://ernst-haas.com/essays-on-haas/

3 Ernst Haas, letter to Wilson Hicks, editor of Life, in response to his invitation to join Life as a staff photographer, London, November 30, 1949. [SOURCE?]

4 Ernst Haas, “Black and White Versus Color”, Writings by Ernst Haas, Ernst Haas Estate, https://ernst-haas.com/writings-by-haas/

5 Haas, In America, p. 151.

6 Haas, In America, p. 12.

7 Haas, In America, p. 133.

8 Ernst Haas, quoted in Inge Bondi, Ernst Haas: A Color Retrospective (London, 1989), p. 11.

9 Ernst Haas, “Color Theories,” Writings by Haas, https://ernst-haas.com/essays-on-haas/

Ernst Haas (1921-1986) is recognized as one of the great photographers of the 20th century, and one of the pioneers of color photography. He was born in Vienna in 1921 and started photographing after the war. His work on the return of Austrian prisoners of war caught the attention of LIFE, but he declined the offer to become one of the magazine staff photographer to maintain his independence. He joined Magnum in 1949 at the invitation of Robert Capa, and became friends with him as well as with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Werner Bishof.

He moved to New York in 1951 and soon began using Kodachrome color film, eventually becoming the leading color photographer of the 1950s. : this was the largest color report ever published by the magazine (Images of a magic city. Austrian photographer finds fresh wonder in New York’s familiar sights).

In 1962, just before retiring, Steichen devoted the first color photography exhibition to him at MoMA, fourteen years before the famous Eggleston exhibition.

Haas traveled extensively throughout his career, working for LIFE, Vogue, Look or Esquire. He published several books throughout his life: The Creation (1971), In America (1975), In Germany (1976), and Himalayan Pilgrimage (1978). In 1986, the year of his death, he received the Hasselblad Prize.

Ernst Haas : The American West

Until January 21, 2023

Les Douches La Galerie

5, rue Legouvé 75010 Paris

www.lesdoucheslagalerie.com