With an audience of over 100,000 enjoying free admission to the exhibitions and screenings by 80 local and international photographers, the Yangon Photo Festival in Myanmar ( formerly Burma) has turned into the most important photography event in South-East Asia. Its prestige is coupled with newly won freedom of expression under the new government headed by Aung San Suu Kyi, who has presided over the jury since her release in 2010. As a sign of changing times, the first prize she handed out was awarded for a story covering the clashes in Kachin State, the site of the main armed conflict still ongoing in Burma.

For its ninth edition, the Yangon Photography Festival set its sights even higher than in previous years, both in terms of its programming and its symbolic message. Between March 3rd and 19th, 2017, the festival attained its ultimate goal: to reach, by means of images, the widest possible Burmese audience in the very heart of the country’s economic capital.

If the Yangon Photography Festival is enjoying great prestige in Asia, it is because it is much more than a simple art event. From the very start, the founder of the YPF, Christophe Loviny, has operated on a dual track: showcasing exhibitions that otherwise would not be accessible to the public while at the same time educating a new generation of Burmese photographers in tuition-free, intensive master classes.

Staging five major photography exhibitions in the heart of the city, in the Maha Bandula Park in front of the City Hall this year, however, was a true feat. In previous years, the festival was confined to the gardens of the Institut Français in Yangon, the only oasis of free speech under the military regime. The audience was similarly composed of the local cultural elites and expats. This year, the YPF spread its wings in the most populated and vibrant place in Yangon (formerly Rangoon). It deployed an ambitious events program among family picnics and happy shouts of children. And, what’s even more remarkable, the festival encountered no opposition on the part of the government. The mayor of Yangon, Muang Muang Soe, was even proud to emphasize the fact: “The situation in Yangon has changed. The festival will not be subject to any censorship. I repeat, no censorship!”

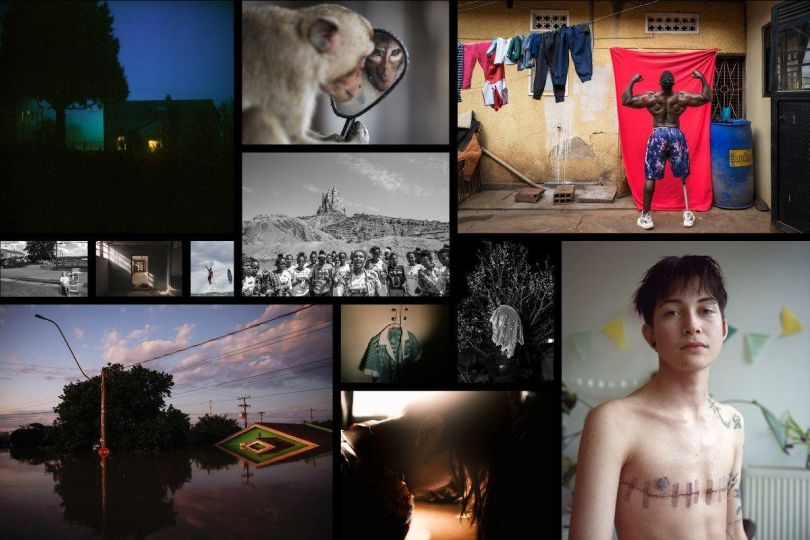

And so, the Maha Bandula Park freely welcomed World Press Photo, which brings together the best of international photojournalism. Subjects ranging from the refugee crisis to the civil war and famine were in plain view for the Burmese public, something unimaginable even a few months earlier. This was the first time in its history that World Press Photo held a free exhibition in a downtown park. In terms of photojournalism, the country is most efficiently making up for the lost time.

Among the exhibitions in this edition, the visitors discovered Burma Frontiers, a collection of rare, early twentieth-century photos by James Henry Green, a British recruiting officer who took advantage of his missions to make the first portraits of thousands of members of ethnic minorities living in remote areas of Burma: Shan, Chin, Kachin, Karen, Padaung, and others.

Similarly, Günter Pfannmüller and Wilhelm Klein seized the opportunity to be the first occidental journalists authorized to travel across the country in the 1980s and, in a large itinerant studio, photographed the diversity of the different minorities, brought together under a common heading: dignity.

The exhibition Yangon Fashion 1979 in turn presents black-and-white archival images from Studio Bellay, rediscovered by the curator Lukas Birk. At the time of the dictator Ne Win’s Burmese Way to Socialism, the country was closed to the outside world. Photography studios were the only places where women in the state capital could try on Western fashions and brighten up their day thanks to outfits smuggled in by sailors.

Landry Dunan, a French photographer based in Bangkok, had spent the days leading up to the festival photographing downtown Yangon residents with his Afghan box camera. He then displayed his black-and-white photographs in the Maha Bandula Park, while inviting curious visitors to have their portrait taken with his camera obscura.

At the Institut Français, the famous Swiss photo reporter Dominic Nahr exhibited his work covering the conflict in South Sudan, as well as taught a master class. “He’s a genius!,” his students would exclaim when describing his photos. Dominic returned the compliment, admitting that he had not expected such quality work from young Burmese photojournalists who have nothing to envy Western counterparts.

The essence of the YPF undoubtedly boils down to turning photography into a new language that allows the young Burmese generation to express themselves.

In practical terms, this key aspect of the festival was made possible thanks to the master classes offered tuition-free by PhotoDoc, the association behind the Yangon Photo Festival. At a time dominated by digital technologies, when banal photos are flooding social networks and new tools make it possible for just anybody to become a photographer, the training offered by PhotoDoc sidesteps the technical knowhow in order to concentrate on fundamental issues and on acquiring journalistic and visual narration skills. Christophe Loviny thereby answers his own question: “We spend years learning to write, but where are we supposed to learn the language of images which we use all the time on social networks?”

This unprecedented desire to raise a new generation of Burmese photojournalists has already paid off. In nine years, over 650 young people attended the photography workshops, first at the Institut Français, then in the most remote regions of the country.

Over the Christmas and New Year season, PhotoDoc set out for the Kachin region, currently torn by conflict between the Burmese Army and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). Christophe and his Burmese team taught photojournalism to over a dozen young refugees forced to flee the fighting.

The results of these master classes are most often three- to four-minute stories tackling social, cultural, or environmental issues. The topics chosen by the students may be universal, such as child labor, human trafficking, the LGBT community’s struggle for equality, the experiences of physically or mentally handicapped, etc. However, on occasion, they deal with local situations that have never been covered by foreign journalists, such as jade mining or the plight of the Rohingya people. In Kachin State, young Burmese photographers documented the civil war, the ethnic minorities’ struggle for survival, and the transformation of their hometown into a ghost city, but they also addressed less tragic topics, such as adapting traditional Kachin recipes to the precarious life conditions in refugee camps.

On the occasion of the Yangon Photo Night, March 11, presided over by the godmother of the festival, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the awards went notably to two Kachin photographers. In the emerging photographers category, the first prize was awarded to Seng Mai for his photo essay The Trap about women addicts in jade mines, while the first prize in the professional category went to Hkun Lat for his coverage of The Forgotten War along Kachin Independence Army front lines. Aung San Suu Kyi handed out the prizes in person, even after having been vehemently criticized in some of the stories. The festival director, remembering the title of the Nobel Peace prize winner’s famous essay collection, Freedom from Fear, underscored the symbolic significance of the occasion: “For the first time, the Burmese are no longer afraid to freely express their opinions before their leader.”

These two awards were a great tribute to the investigative work done by Burmese photographers and to the association’s master classes, supported by Canon as well as by local groups, such as Myanmar Golden Rock, KBZ, Shwe Taung, and Novotel Max. The photo stories screened at the Maha Bandula Park, created as part of previous years’ master classes, were also a huge hit. From the very first seconds of the screening, the festival resounded with shouts translating the astonishment and delight of an instantly gratified public. And as soon as the presentation was over, their eyes still riveted on the giant screen, sometimes with a mobile phone to record everything live, the audience never waited long to show their approval. Even while the featured videos often addressed social plight, they always got a standing ovation.

It would be an understatement to say that the audience, numbering about 6000 every night, was optimistic, curious, and supportive as they listened between screenings to speakers from different organizations discuss such issues as child labor, domestic violence, or prevention of infectious diseases. One of the highlights of the two evenings of screenings was an improvised fundraiser prompted by the heartrending sight of a little girl beggar featured in the story For Mother. Hossein Farmani, a gallery owner, philanthropist, and long-time supporter of the YPF, pledged before an engaged public: “I will double the total amount of your donations!” He then added: “Remember the names you see tonight. Remember the photographers. If you run into them, thank them or give them a hug, they are your heroes,” he said, having presented a rare selection of Steve McCurry’s work, currently on view in an exceptional retrospective at the Lucie Foundation Gallery in Bangkok.

The country has undoubtedly made huge progress since the Saffron Revolution of 2007, when some Burmese, armed only with their cell phones, filmed the repression of protesters, thus becoming the first photojournalists in a country known for the brutality of its leaders. Today, photography has become a lever for positive change in the country.

To borrow the words of the photographer REZA, “while one photograph can’t change the world, it can change human beings who can change the world,” and the ninth edition of the Yangon Photo Festival is an excellent example.

The second poorest country in Asia after Afghanistan, Burma stripped bare by its own citizens, giving a voice to those who, until recently, were being silenced. The Eye of Photography will revisit some of the noteworthy YPF exhibitions and bring you a selection of the photo essays. You will see them just as if you were seated on the grass at the Maha Bandula Park, intoxicated by children’s laughter and moved by discreet tears of emotion welling up in people’s eyes.

An invitation to discover the world.

Aline Deschamps

Aline Deschamps is a journalist, photographer, and a cultural project manager working in Paris and Bangkok.

9th Yangon Photography Festival

Yangon, Burma

Some of the exhibitions are still on view throughout the month in Junction City, the new shopping mall in the city center across from the central market.

http://www.yangonphoto.com

www.facebook.com/myanstories/

www.facebook.com/yangonphotofestival