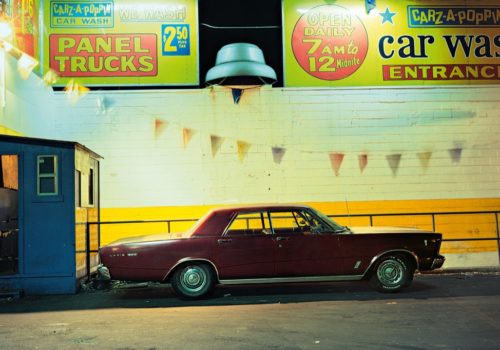

Between 1974 and 1976, Langdon Clay wandered New York’s streets taking pictures of cars. He shot them parked on the street, at night, bathed in a sense of waiting that Edward Hopper would understand. The cars? They’re like New Yorkers: some stars, some bums, some big guys (mostly big guys), in all colors and of all dispositions, the tricked-out and the banged-up. He shot them using a Leica and Kodachrome, and in such a careful, observant way that 18-foot-long Chevy Impalas and tri-tone Buick Electras fit seamlessly into their surroundings—so seamlessly, in fact, that you’d think they were born there. Clay’s book is called Cars but cars are only part of the story; he’s created a time capsule of New York in the ’70s, and a haunting reminder of just how big the night can be. Recently, The Eye of Photography spoke with Langdon Clay in a phone interview from his home in Sumner, Mississippi, (pop. 300) about how he made Cars—and how, after 40 years, it became a book.

How did you come to this project?

In the early ’70s, New York was down on its heels but I was in my 20s, it didn’t cost a ton to live there, and it was visually totally appealing. I would be at friends’ apartments downtown and then, at night, I’d walk home to my apartment on 28th Street. I always had a camera with me, and I started shooting street scenes with a lot of cars. It took a while but I began to winnow it down, focusing on a single car. Somehow in that process, night became important to me. I got hooked and it started to feel like there was something there.

The book is called Cars, but I found myself entranced by the backgrounds— the windows, walls, and signs. Was that part of the idea from the beginning?

The car itself didn’t matter; it was how it merged with the background. That’s the aesthetic, and that’s what photography is so good at: synthesizing two kinds of things, like color and design. So those elements coalesce in the images. But in those days, cars had artistic style; they were designed by people who would model them by hand. The cars today don’t have that character; they’re interchangeable.

It’s the middle of the night, there’s garbage on the ground and graffiti on the walls, but your colors are so beautiful and so subtle.

I had just switched from black-and-white to color and this was my first project. I went at it with zeal and I became obsessed. I had to go for this crazy color because I wanted to separate my work from my “photo parents”: the Magnum-style photographers and the art-photographer black-and-white scene.

In the book’s afterward, you write that “Night became its own color.” That’s such a wonderful line. What do you mean by that?

You get to the gloaming and then you get to full-on night. When the streetlights are on and car headlights are there and neon and fluorescent are reflected, that became a different color, its own color. Walking around on New York’s streets at night, it’s different than walking during daytime. I’m still intrigued by it.

In the ’70s, the streets of New York weren’t all that safe at night. I’m curious about your method: What was the hunt like? Would you identify a place and wait for the right car to pull up in front of it?

Most of the photos were made in the West Village or Hoboken. Walking around those streets for two years, you’d cover the same ground over and over, and certain buildings would appeal but nothing would happen in front of them. And then one night something would happen and you’d record it. You’d be so keyed into it, kind of like a scientist trying to sort something and it all comes together in an instant. That’s when it starts to sing. It had to reverberate, had to work together. You could just tell. And then there were times when you’re photographing and something happens beyond the nominal subject that even you don’t see until later. That’s the fun, actually.

Why did you decide not to include people?

I didn’t decide. There are actually some people but they’re ghostlike. The exposure was 40 seconds, so unless they stopped, they wouldn’t be in it.

The book has 115 images. How many pictures did you make in your two years of shooting?

I’d say about 200. You had to be careful because with film it gets expensive. After a couple of months, it becomes easier and you wouldn’t even be wasting film.

Which was the first picture that made you feel like you’d caught what you were chasing?

There’s one with a gold car and a green tree right behind it and streak of taillight running through the frame, and up in the corner there’s a fire escape in the fog. That was the first one that made me think I was on to something color-wise. It’s the picture that made me think, Ok, this is cool. If you think of images as time capsules, it’s the time capsule.

Was this project influenced by any photographers?

I got permission from Hopper and Brassaï—in other words, to focus on night as a subject. The cars, from Atget and Evans. And Eggleston is an influence in that he made color acceptable—but you don’t want to imitate him. I knew him back then; he would actually sleep on our couch once in a while. I would tell him I wanted to meet [MoMA Director of Photography John] Szarkowski, and he would say, “You’ve got to cut your teeth, you’ve got to wait your turn.”

What about Bernd and Hilla Becher? The repetition of their subject matter made the subtle variations really jump out.

Yes, the photographs compound their value in association with one another. I got to their work through the magazine Camera in the ’70s and was totally impressed by it —and am still impressed. It just makes you realize that anything can be photographed. But what makes it good? That’s still an open question…

So you shot these scenes in the early ’70s. Why is the book coming out now, 40 years later?

Pure luck. A few years ago, my wife [photographer Maude Schuyler Clay] sent an email to Gerhard Steidl [the publisher of Steidl books]. Out of 1,500 requests he gets a year, he only responds to two. And he responded to Maude. On July 4, 2014, Gerhard came to Sumner, Mississippi, the little town where we live and where we raised our kids. He came in a limo and spent four hours. We have a big table and he ran through all these prints, both Maude’s and mine, putting them in stacks. He goes through them very fast but he’s very precise and totally focused. He flew here with a big empty suitcase and when he packed up our originals, I just crossed myself. Then he left and went to Memphis and visited Eggleston—who happens to be my wife’s cousin—and flew back to Germany. He didn’t even spend the night in the country.

After 40 years, how did that feel?

I thought finally! I always liked the stuff and I still do, and I think it’s become a record of the ’70s. I liked them as images and the iconography and the background and how they work together. And I always loved New York.

What do you think when you look back on these pictures?

I’m 67 now and I’ve been living in a rural area for 28 years, so when I look at the pictures it brings me back to the feeling of what a city is and of what makes a city. I’ve always loved urban photographs, of New York and of Paris, and I’m still drawn to those centers. It’s something in me. I’m not an expressionist. I’m not trying to use photography to express internal emotions. I’ve always been interested in recording stuff. But you have to do it at the time; if you only photograph what’s nostalgic, you’re missing your mission. And the mission for me is always to get the current era, and not because it will become a book 40 years later.

Interview by Bill Shapiro

Bill Shapiro is the former editor-in-chief of LIFE magazine; @billshapiro on Instagram

Langdon Clay: Cars – New York City, 1974-1976

Published by Steidl

$95 – €85

https://steidl.de/