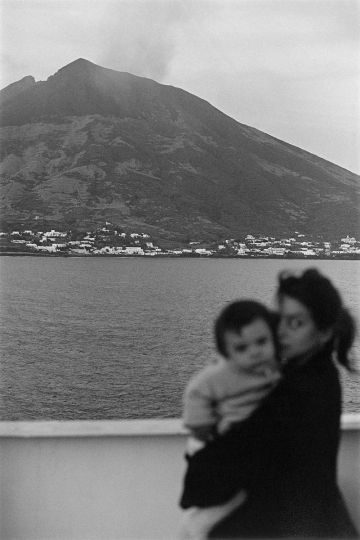

Daniel Foliard’s Combat, Punish, Photograph explores early conflict photography. The focus is on still images of physical and armed violence. The book is based on an extensive use of previously untapped archives, from private albums to pioneering photo agencies. It shows how French and British societies between the late 19th century and 1914 were regularly exposed to a range of raw images, contrary to the conventional wisdom that war in general, and colonial conflicts in particular, were invisible at the time. The expansion of empires in Asia and Africa in the late 19th century created a conflict-ridden world whose wars were nevertheless often remote, from a European standpoint.

For French and British societies, the last close-hand experience of mass armed violence before the 1910s was the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. For a period of four decades, war, often in the shape of colonial conquests marked by eruptions of extreme violence, could thus seem a far-away reality for Europe’s imperial metropolises. With the growing portability and affordability of cameras photography became a more democratic tool through which to record and collect events or memories. And with the visual economy of organized violence considerably shifted, in the years before the world wars.

This books thus seeks to question the chronology of war photography and, in doing so, to suggest ways to make images not merely the illustrations but the integral parts of the argument. It is, in this sense, a book on photography and with photography. It goes beyond an exploration of images of death and destruction. It is a proposal to engage in a painful conversation on the way we read and re-mediatize photography, doing so with deference and the requisite attention to context, but without any excessive iconophobia. This is not a work that cultivates disaster pornography. It is a carefully researched invitation to make sense of extreme documents, to neutralize them through words instead of being submerged by the initial shock they inevitably produce on the beholder. And it shows that photography can never fully victimize its objects, as long as the observer knows how to look, even when she or he stares into the heart of darkness.