In the wake of the March 2011 disaster, Japanese artists were all naturally drawn to the subject. The common thread in their work was to show the effects of radioactivity. Masamichi Kayaga, for instance, sought to visualize the invisible by creating radiographic plates of objects found in the contaminated zones.

In France, however, even while nuclear energy is paramount and while EDF, the French utility company, has recently signed an agreement with the UK to build two nuclear power stations at Hinkley Point, the topic has had little resonance in art.

The Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris is bridging this gap by going behind the scenes and showing the effects of the nuclear power industry. The visual artist Hélène Lucien and the photographer Marc Pallain spent several months visiting the contaminated zones around Fukushima in order to construct this immersive and sensory exhibition.

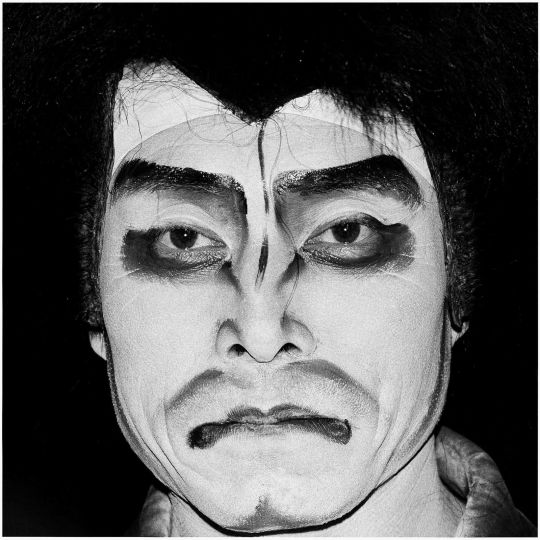

We discover stunning “chronoradiograms”— radiographic film which captures x-ray images, the same as those used in medical practice. But we also find videos shot in the zone, photographs, a Playmobil scale model, and installations. All this is coupled with Floyd Krouchi’s audio creation, designed using sounds recorded in Fukushima, which transports us into those bleak, dreadful landscapes. Without any hint of voyeurism, these two artists attempt to reveal the invisible. L’Oeil spoke with Hélène Lucien.

How did you go about exploring the areas around Fukushima contaminated in the wake of the disaster?

Even before March 11, 2011, we had planned to do a project on urban spaces and architecture in Japan. We were in the process of brainstorming when the nuclear disaster struck and became the topic of our research. We were selected to participate in an artist’s residency, Tokyo Wonder Site, and we left for Japan for three months.

What did you intend to show?

I had a very strong intuition: to visualize radioactivity. So I thought about using radiographic film, the same that is used in medical x-ray imaging. It was a veritable artistic risk, since we had no guarantee it would work. We began placing our x-ray film plates throughout the contaminated zone, without knowing how long they should be exposed. We retrieved them three to thirty-seven days later. We then repeated the process in May 2016, on our second, month-long visit. Our goal was to have an element of comparison with our first results from 2012.

This is certainly an artistic approach, but it also calls for some scientific background…

We were both trained as mathematicians; I studied at the Institut Pierre et Marie Curie. There, I became interested in their work in radioactivity. I also knew of Christian Schad’s schadographs and Man Ray’s rayographs. All this gradually came together in my mind.

This exhibition seeks to awaken all our senses.

Exploring an invisible phenomenon is quite complicated. But thanks to chronoradiograms, viewers will be forced to recognize that radioactivity is not nothing. We do not pretend to give any answers. However, I am convinced that the sound combined with the image will offer a fuller sensory experience. This is about a physical confrontation since, even when you are physically on location, you cannot feel anything. You only hear the beeping of your dosimeter.

There is also an experience of absence, especially in the room with those enormous sandbags, just like in the contaminated zones in Japan, and those hollow human figures.

These sculptures signal absence and represent the ghosts haunting these zones, since all their memories have been left behind.

Is visualizing radioactivity a militant gesture?

It’s more about raising questions and spurring people to think about nuclear power. For example, the Playmobil scale model is a sore point for the Japanese government, since they want to resettle people in these zones. The official message is that it is safe to live in radioactive zones. Human beings are capable of adapting, but at the cost of how many sacrificed generations? Human beings can live in those areas, but they won’t be able to walk through a forest, since the trees have been contaminated. The Japanese government is proposing a half-life.

Is it this half-life that you evoke in your photos of Kawaii (“cute”) young women with their sparkle dosimeters?

Our own country is in danger of facing a similar disaster, since our nuclear power facilities are aging. Perhaps ten or twenty years from now, everyone will need a personal dosimeter? It might become a must-have fashion accessory, and so an object of desire marketed by designer labels. Our future is not all that rosy. The next step is to make this a traveling exhibition and develop it depending on the destination. Why not take it to Japan, or to Ukraine for a confrontation with Chernobyl?

Cécilia Sanchez

Fukushima: the invisible revealed by Hélène Lucien and Marc Pallain

Until October 30, 2016

MaisonEuropéenne de la Photographie

5/7, rue de Fourcy

75004 Paris