by Igor Manko

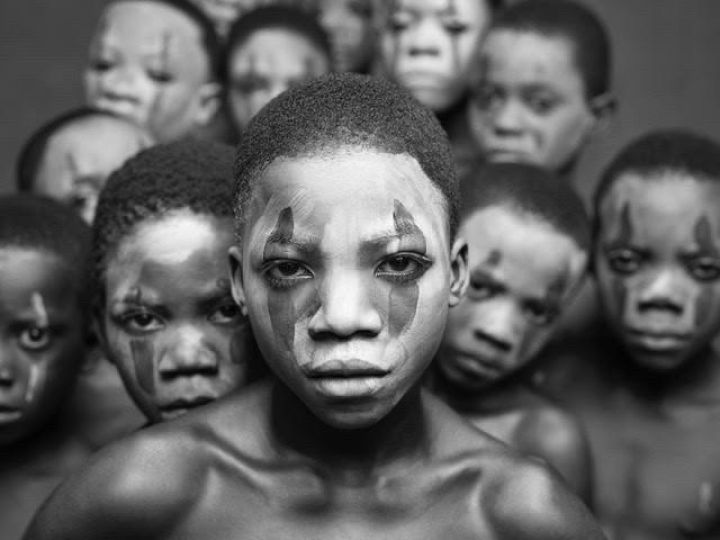

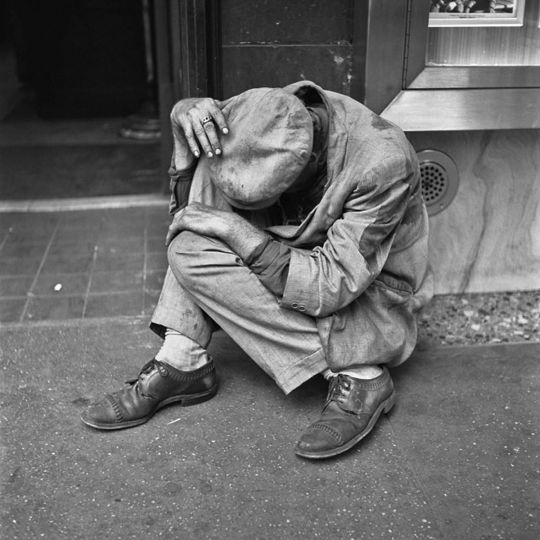

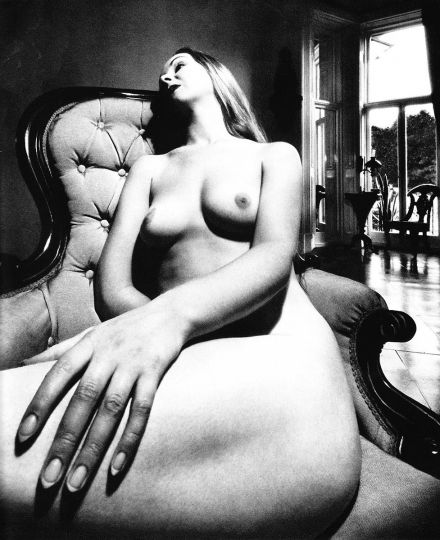

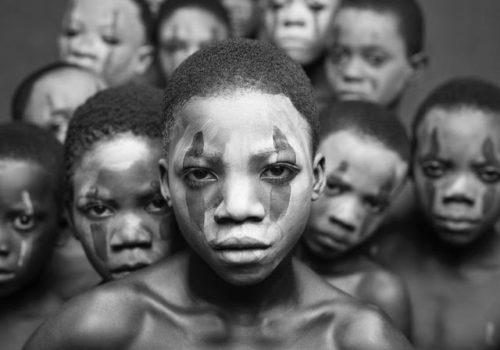

In the 1970s, a collaboration of eight rebellious artists (the Vremya group) brought to life a distinctive and recognizable visual language of art photography, with the blunt, uncompromisingly straightforward treatment of controversial Soviet subject matter. Boris Mikhailov, an internationally recognized photographer nowadays, was their informal leader and the engine of the group’s activities. Vremya group’s imagery pictured forbidden details of Soviet reality, from naked bodies to the bigotry of communist propaganda.

Due to strict censorship, Western art magazines in Kharkiv were scarce (except the Soviet bloc countries photo periodicals) and trends in fine art photography on the other side of the Iron Curtain were almost unknown. As a result, Kharkiv photography was not imitating Western imagery; the artists had to invent their own approaches to the portrayal of Soviet realia, expanding the notions of acceptable subject matter and creating their own style — in nude, documentary, or other photographic genres.

They favored manipulations with a photograph, like overlaying slide frames, hand-coloring, and collaging, while the official style required only realistic depictions. They formulated the ‘blow theory’ which required an image to produce the effect of a punch in the face.

“Overlays”, or “superimpositions”, were probably their first inventions on the way to new and more complex means of visual expression. Boris Mikhailov says that while he intended to take a look at newly developed slide films, he incidentally put two of them together and was stunned by the effect. The images looked formally new, surrealistic, and grotesque. The technique produced a result similar to multi-exposure but allowed clearer detailing and freed the artist’s hands for countless combinatory possibilities. Two overlaid color slide film frames were either screen-projected in a slide show or printed on color photo paper. Mikhailov’s work in this technique, as in all his œuvre, has an acute social focus.

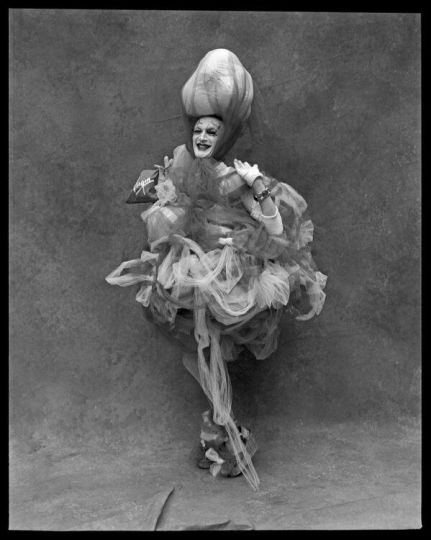

In the 1970s, Kharkiv photographers often earned a living by copying and enlarging people’s family photographs. It was an illegal commercial practice commissioned by people living in rural areas, often in remote parts of the country where color studio photography was either too expensive or simply non-existent. A specifically Soviet product, a ‘lurik’ in photographers’ jargon, was a mounted or framed enlarged and retouched hand-colored portrait, postmortem portraits included. Family or passport photos by origin, they often carried instructions to the photographer: to remove a hat or add more hair, make a montage combining people from different images in the one photo of a would-be family, etc. Boris Mikhailov conceptualized these pathetic examples of true folk art in his Luriki series (1971—1985), “the first strategic use of found material in contemporary Soviet photography” (John P. Jacobs).

The hand coloring of black-and-white images responded in kind to the complexity and expensiveness of the color process. Kharkiv artists used the technique of hand-coloring in a variety of ways: from subtly highlighting a certain detail of the image all the way to making a photo look like a coloring book page. The latter was characteristic of Victor Kochetov’s brutal and uncompromising approach. He turned his originally realistic black-and-white scenes of shoddy everyday workings of Soviet lifestyle into a work of kitsch as if taking to its extreme the social realism principle of showing the brighter side of reality in an effort to change it by means of art.

Evgeniy Pavlov’s Montages (1989—1996) made a further step in formal experimentation. In these works, the artist rejected all attempts at imitating a ‘straight’ photograph: black-and-white and color scraps, manual coloring, and scratching resulted in masterful and complex images. Dust and scratches on film emulsion, ragged edges of torn-out fragments, and other artifacts were all transformed into elements of his visual language. This approach was elaborated in Pavlov’s 1990—1994 Total Photograph project (about 100 images). It illustrated his concept that any photographic image (including any found material) can be transformed into a work of art. Pavlov used all possible techniques available to him to demonstrate that, from manual coloring and drawing to montage and intentional film damage.

Igor Manko

To learn more about the Kharkiv School of Photography visit the platform Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. The platform is a part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute and is dedicated to the promotion of the Kharkiv School of Photography achievements among the wider international audiences and its introduction to the all-European artistic context.