By Halyna Hleba

Based on PinchukArtCentre Research Platform materials

Modern Ukrainian conceptual photography began in the 1970s in the then Soviet Kharkiv with the emergence of a generation of young people who dared to go beyond the Soviet aesthetics. Members of the Vremya art group developed the “blow theory” in the early 1970s as their own idea of art photography, in which corporeality was a tool against the pseudo-optimism of socialist realist photojournalism where the image of the naked body was banned by censors and considered a dangerous outrage.

At that time, the body in Ukrainian visual culture was a trigger of morality and traditionalism, an artistic instrument of social and critical expression, and since then it has become a metaphor for the boundaries of individuality and personality, even in independent Ukraine.

***

In 1960, Soviet law banned the depiction of the naked body: it was considered pornography and therefore a criminal offense. At the same time, in the United States and Western Europe, socially conservative norms of perception of corporeality and sexuality were broken by the so-called sexual revolution. This was the time of the Cold War and the confrontation between the USSR and the USA, the opposition of one political system to the other. The documentary nature of photography was the feature that emphasized the polarity of body perception in society and culture.

In the Soviet Union, where the prevalence of censorship and bans made the depiction of any manifestation of sexuality illegal, be it literal eroticism or nudity as a metaphor for intimacy, the naked body for Kharkiv photographers became a tool to release internal ideological and political tensions. In the aftermath of the political “Thaw” it was felt most acutely by young critical people and required a reaction.

The reaction to the boring official Soviet photography in Kharkov in 1971 was the emergence of the Vremya group – an alternative association of young photographers at the city photo club. Among the group members were Evgeniy Pavlov, Boris Mikhailov, Yuri Rupin, Oleg Malyovany, Alexander Suprun, Alexander Sitnichenko, Gennady Tubalev and Anatoly Makienko. It is from the activities of the members of the “Vremya” group that the Kharkiv School of Photography originates. Behind the Iron Curtain, far from the current world culture and art, surrounded by official Soviet photography in magazines and newspapers, the young artists in a circle of like-minded people independently developed an understanding of what they thought was true photography — the one that can touch the viewer and attract their attention. In personal conversations and kitchen discussions, a “blow theory” emerged, according to which the artists positioned photography as a work of art in opposition to pseudo-documentary official Soviet photography. Manifestation of the concept of “blow” was a bright, aggressive photography, which literally “beats the viewer” and forces them to respond to the photographic image. And the naked body and “naked sociality” became its main subject-matter.

To create a metaphorical and alternative reality, the artists boldly experimented with the technical side of photography — they used collage, montage and overlay (so-called “photo sandwich”), colored their photos, emphasized kitsch and thus turned the photo into a reaction to the absurdity of Soviet life.

Each of the generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography worked differently on the subject of corporeality. The first generation, represented in the history of Kharkiv photography by the Vremya group and the decade of the 1970s, identified the naked body with the image of an individual crushed under the pressure of ideology and socio-political control. A decade later, the 1980s generation adopted collage, montage, and other manipulations of photographic documentation from their senior Vremya group colleagues to depict the body as intimate and personal, but with the literality and audacity of the 1980s. Among the Kharkiv photographers of the 1980s were Roman Pyatkovka, Viktor Kochetov, Misha Pedan, Sergey Bratkov, Sergei Solonsky, Igor Manko, and others. The 1990s in the history of Kharkiv art are marked with going beyond a clear photographic framework — the artists practiced performance and installation photography — like in the works of the Group of Immediate Reaction. The collapse of the USSR and the formation of a new political reality saw the body in the oeuvre of Kharkiv photographers acquire theatrical features, reflection of new social constructs and, accordingly, new roles.

The female body

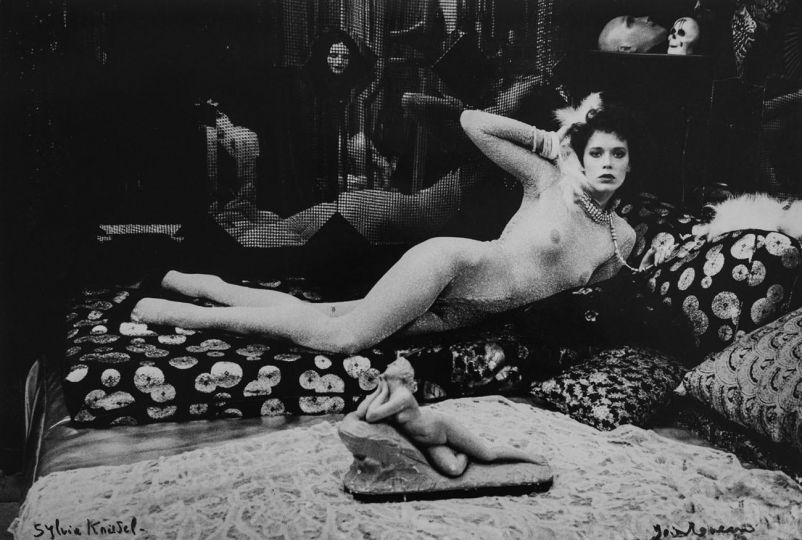

The body in Soviet photography was taboo, but still naked women were photographed, even if not exhibited. According to Borys Mykhailov’s memoirs, Kharkiv artists first saw photographs of naked women in Lithuanian photography, as Lithuania was one of the most pro-Western Soviet republics. And after the foundation of the Lithuanian Union of Photographers in 1969, the first professional association of photographers throughout the USSR, Lithuania became the only “photographic republic” in the Soviet Union and a model for photographers in other parts of the country to follow. Lithuanian photography with its humanistic accent represented a “new look” in Soviet culture. The Naked Lithuanian woman was romanticized and poetized by photographers.

Lithuanians were very sensitive to the limits of what was allowed to them, as outlined by the Soviet authorities. On the contrary, Kharkiv photographers were under the close control of the KGB after their first public meetings inside the club as the Vremya group. Their photography was conspicuous, sometimes outrageous, almost always with a touch of sociality and criticism of the Soviet regime, as well as with the inherent for the Soviet intelligentsia “tongue-in-cheek“ attitude — an internal protest against bans and censorship.

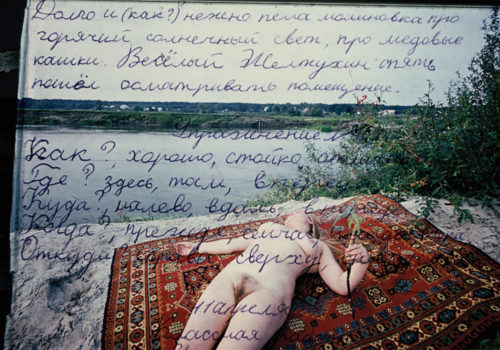

For example, Boris Mikhailov created the first works of the famous Overlays series (also known as Yesterday’s Sandwich) in the late 1960s. The peculiarity of Mikhailov’s “overlay” was not exclusively a naked body, the series is rather one of the brightest examples of conceptual social photography with a sewn-in metaphor of two layers of the literal and hidden Soviet reality. According to Borys Mykhailov, “where the text from school notebooks is superimposed on the image of a woman, a rather kitschy picture emerged. The text overlays the woman from above, and it seems to” fuck” her like a man.”

The models of Kharkiv photographers were mostly girlfriends and wives — women from close circles. Such nude photos violated the image of the Soviet woman of that time, but fully agreed with the canon of female attractiveness in the eyes of young people from Kharkiv. And if the female body in Oleg Malyovany’s photograph was obviously attractive and aesthetic, Boris Mikhailov’s naked photos were the opposite of the aestheticized examples of female beauty and femininity. In Mikhailov’s photos, the woman is not idealized, her body is presented old, young, thin or corpulent, but diverse. Attractiveness for Mikhailov becomes a marker of the idealized Soviet picture, which he opposes by means of photography.

Oleg Malyovany was fascinated by a different aesthetics in photography, richly decorated with visual effects. In his photograph, the body is represented by the color and “melting” of the shape. There is no sociality in his interest in the female body, but there is an undisguised fascination with his heroines. For example, in Waiting, the author uses a wide-angle camera to portray a girl sitting on a chair with her head thrown back. In this perspective, the image seems to melt before the eyes of the viewer, creating a feeling of narcotic dope, as if blurred by a drop of gasoline in a puddle of various shapes and colors.

The body of a Soviet person actually belonged to the Soviet government. Soviet society perceived itself as a body, a corpus, with an opposition of mine / theirs, official / unofficial, and even a highly subjective opposition of beautiful / ugly. And just as a Soviet citizen did not want to reveal his soul to a foreigner, the Soviet body was forbidden to expose itself to the world. But the body in the late Soviet alternative culture was by no means limited to nudity: it is defined both as the social cog of Soviet society and as the embodiment of the individual in a non-conformist culture.

Therefore, modifications of the body, the introduction of foreign elements into its integrity and appearance, whether piercings, tattoos or even non-compliance with the norms of appearance adopted in Soviet society, were regarded as a manifestation of dissent, marginality and identified with the prison subculture. Partly because of this, the modification of the image of the body in art was also perceived as an attempt to disrupt the natural “perfection” of the human body, to lead it out into the formal plane.

Gennady Tubalev, another member of the Vremya group, practiced body fragmentation and the construction of a new body shape. His work The Ghost of Matriarchy (1971) is a montage, a contrasting black and white symmetrical image, assembled from photo-fragments of the female body — breasts, roundness of the thighs and waist. Tubalev materializes the bodily form, makes it similar to the objects of decorative and applied art — the body is represented as a vase or a whimsical vessel. For Soviet art, especially photography, with its extremely unambiguous function of documenting reality in Soviet society, such an approach became a dangerous manifestation of the condemned formalism.

The male body

The sexual revolution in Western culture was the opposite to the Soviet idea of a family as a “center of society.” The process of freeing the body from the shackles of religious moralism was a post-revolutionary agenda of the 1920s and a testament to progressive socialist ideas in the former Russian Empire. The second wave of sexual liberation was brewing in the 1960s, in parallel with the sexual revolution in the Western world. This internal tension of Soviet society did not erupt into the masses with the ideas of sexuality, but turned into an internal turbulent volcano of the desire for freedom.

If naked femininity in Kharkiv photography appears to be the same as in the works of Lithuanian colleagues, the naked male body was photographed much more boldly than by anyone in the USSR. The danger of portraying a group of male naked bodies was in the fact that it was perceived by the Soviet authorities and society as propaganda for homosexuality. For post-Soviet society, this subject-matter was still stigmatized, and in the Soviet 1970s it was punished more severely than the image of women’s nudity. Even an attempt to depict a naked body in a public space outside the “natural conditions of permitted exposure” — baths or hygienic procedures — was already a political anti-Soviet gesture.

Significant in the history of the Kharkiv School of Photography is the 1972 Violin series by Evgeniy Pavlov. In this work, the artist portrayed a group of male nudes in nature, one of the first male nude photoshoots in Soviet photography. Pavlov’s male body is a poetic image of openness and freedom, a metaphor of defenseless dissent. And although the artist did not film it with literal homoerotic references, the socio-political conditions of complete secrecy and non-publicity of the LGBT community in the Soviet Union affect the perception of these male images today.

That same year, photographer Yuri Rupin created the Sauna series, which is also a men’s nude group photoshoot, but made during hygienic procedures. The vapor envelops the characters, veils their nudity, creates an imaginary screen that covers the models and gives the whole series a sense of spying. The photographer deliberately goes beyond what is allowed by Soviet censorship, but still does not violate it, because Soviet censorship allowed exposure in visual culture only in images associated with hygienic procedures. With this reportage series, Yuri Rupin seemed to flirt with the Soviet system of censorship and legislation. The body in Yuri Rupin’s photographs was not just an attempt to provoke the authorities with literal corporeality in the categories allowed by it, but also an awareness of one’s own body as the last frontier of privacy and inalienable experience.

Travesty as an artistic method

The visual culture of the Soviet Union strictly regulated both corporeality and gender. The body had to meet the norm and, according to the gender, female body emphasized the “maternal tasks of a woman”, and male one asserted strength, reliability, and stability.

But in the conditions of pseudo-reality of Soviet visuality, Kharkiv photographers felt that real life exists according to other laws. Boris Mikhailov recalled that “the person at that time was already different.” First of all, it was about a person’s views, their behavior. But in the life of a Soviet person there was a place for another bodily representation: a man could also be sensual, sentimental and tender, and a woman had the so-called “masculine traits” — strength of will, determination, and courage. This “bodily hybridity” became apparent during Perestroika, and Kharkiv photographers could capture the image of how the political Perestroika affected the restructuring of the physical.

Along with irony, kitsch and destruction in photography, Kharkiv artists used travesty images in order to emphasize the process of transition between real and fictional. Thus, they constructed a metaphorical image of transgression. Travesty, and more specifically — disguise, was a game in fictional circumstances, in which heroism and seriousness were depicted humorously. Such a method is characterized by provocation, carnivalization, and a combination of high and low genres which Kharkiv photographers also borrowed from Lithuanians. But they played more dangerous games — they flirted with the nomenklatura, the law and the government.

For example, in Boris Mikhailov’s autobiographical Viscosity series (1982), remarkable is a self-portrait in which the artist poses and assumes a stereotypically “feminine” pose, imitating mannerism and bodily flexibility, as if blurring the line between the sexes. In this series, the artist accompanies the photos with notes and texts, which is a characteristic feature of Mikhailov’s “diary” series that recreates a very personal intimate space. The idea veiled by the artist can be literally “read” through angles, poses, images and words.

But not everything that is a game or looks like a game is transgressive in the practice of Kharkiv photographers. An example of a failed staging was Oleg Malyovany’s 1992 Blue Series, which the artist dedicated to the LGBT + theme. In the photos, Malyovany’s hero plays theatrical sketches demonstrating stereotypical female images, for example, trying on balloons like a woman’s breasts. The ridiculousness of staging proves that not every theatricality or play with socially displaced images is a travesty method of working with photography. Such a formal approach literally and superficially illustrated social phobias, and did not affect the rethinking or debunking of the Soviet man’s prejudices against the LGBT + community. Obviously, it was rather a reflection of the fears and stereotypes of the author of the series. The Blue Series is a game where Malyovany’s character depicts a stereotypical and hypertrophied image of a representative of the LGBT + community in the eyes of the then conservative and deeply Soviet society.

But the real visual embodiment of the ideas of the transition between different symbolic and political systems is Sergei Solonsky’s Bestiary cycle (1990–1997). Bestiaries in the history of world culture traditionally were a kind of encyclopedia of the medieval man’s phobias, the fear of the “other” which acquired in bestiaries the features of semi-mythical creatures. Solonsky’s heroes in the post-Soviet bestiary of the 1990s are those who no longer resemble the average Soviet man. Part of this cycle is the 1997 Boudoir series, in which the artist constructs the body combining male and female parts. Sergei Solonsky created the image of a new woman who, during the collapse of the Soviet system, absorbed both masculine and feminine traits: fragility and strength, mannerisms and determination. And thus she became the new woman of the capitalist world. Such a layering of male and female also embodied the layering of the Soviet socialist past with the new capitalist reality. And although the artist, like the Soviet man in general, did not know about transhumans and created exclusively poetic visual images, today his visuality in the Boudoir series is read precisely through the gender optics and issues of the LGBT + community.

Turning to the old visual forms, but speaking of new ideas, Kharkiv artists created a travesty dimension in late-Soviet photography. These images went beyond the norm, and photographers used them to raise the topics that were taboo in Soviet society and outlined the zone of transition from the old order to the new political and aesthetic systems. In the context of those years, Kharkiv’s “acts” in photography existed outside of eroticism, and oppressed and hidden corporeality acquired a critical social interpretation. After all, despite the nudity, the artists saw their works as a social metaphor, not as literal pornography. It became an inner need to expose one’s own thoughts among the members of the “Vremya” group, the openness in working with photography and the perception of it as a means to express their own social sentiments. Ultimately, this was embodied in the ideas of group communication, the emergence of the “blow theory” and the creation of an alternative photographic form in Ukrainian late-Soviet photography and modern culture.

To learn more about the Kharkiv School of Photography visit the platform Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. The platform is a part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute and is dedicated to the promotion of the Kharkiv School of Photography achievements among the wider international audiences and its introduction to the all-European artistic context.