I can honestly say that no one took us seriously – and I had my doubts, too.

The setting was the London bureau of NBC News in the summer of 1998 – a more innocent time in every sense of the word. Brian, then the young director of multimedia at MSNBC.com, was on his first-ever foreign assignment with my relatively grizzled ink-stained carcass.

We were about two years into an experiment that had started to show some promise, at least measured in terms of audience, but which had yet to be classified as anything but an annoyance by the denizens of the network. Not only had NBC News failed to fully embrace the concept of online journalism when it signed a joint venture agreement with Microsoft to create MSNBC.com in June 1996 – it had not even enabled journalists in its major new bureaus to access the internet. The fear, I was told by one network producer, was that ABC News or CBS would figure out a way to see the rundown of Tom Brokaw’s upcoming broadcast.

Into a semicircle of such skeptics walked Brian, ill equipped in so many ways to win them over. Where they regarded themselves as wise and sophisticated correspondents, Brian was determined and profane. He had not gone there to stroke the NBC peacock. He went in to school it.

In a 15 minute presentation strewn equally with passion and expletives, Brian all but traced the trajectory of the forces that would soon undermine the hubris that network news or even broadcast itself was at the top of some imaginary media food chain. Still photography – a nonentity for NBC (or at the very most, a last resort in the absence of video) – was front and center in Brian’s presentation. Audio, similarly confined to a supporting role in television production, was also stressed.

So too was narrative. This put the audience on more familiar ground, though the topics Brian demoed – fears among Europeans about the pending introduction of the euro, audio driven slide shows of the suffering in Rwanda, and a seminal production called “Behind an Iron Veil” we collaborated on with Harriet Logan about life as a woman in the Taliban’s pre-9.11 Afghanistan.

“I get who you are, Moran – you’re a writer,” said Garrick Utley, the venerable correspondent, after the presentation. “But that guy scares me. I’m not sure I understood anything he was saying. But I get the feeling we’ll all be working for him pretty soon.”

If that had been Brian’s ambition, I am reasonably sure it would have happened. Happily, both for NBC News correspondents who would struggle like the rest of journalism to adapt to the Internet, and for photojournalism, Brian had other plans.

Starting in 2005, Brian and the unique production company he founded – MediaStorm – has helped reinvent storytelling for the digital age and, to be frank, helped save much of what we know as photojournalism which might otherwise have disappeared along with the great newsweeklies and other print outlets that once supported such work.

From the earliest projects, including some where I was the driving editorial voice, the insistence of Brian and his team on tapping the best possible talent has set MediaStorm apart from his competitors. The 2006 production “ Crisis Guide: Darfur ,” the second in the series we produced together for the Council on Foreign Relations, featured the work of no less than seven Pulitzer Prize winners. It also launched a new way of manifesting documentary length material online as well as a new ways to “Share” and embed that material around the internet. Not surprisingly, it won a Knight Batten Award for innovation in journalism and an Emmy Award for Documentary work – the first of three the series would win.

Again and again, editorial excellence was married with technological innovation and marketing savvy to produce something that was simply better than anything that came before it – and was quickly imitated by those with deeper pockets.

Ed Kashi, whom I had the pleasure of working with in 2013, has published his work repeatedly with Brian and remembers how Brian and the company he would found in 2005 helped legions of film-shooting photojournalists learn the language of a new style of storytelling.

“MediaStorm opened up a new channel, or space, for visual storytelling that embodies the critical elements of the craft but produced in a wholly new way for the new forms of dissemination that the web offers,” Ed says. “He has staked out this new territory like an evangelist, pushed the world of photojournalism, sometimes kicking and screaming, into these new frontiers.”

Brian, a digital native, found himself dealing with a culture of journalism that soon understood it was under threat. Some, like me and Ed, embraced the new world and found ways to continue producing in spite of uncertain business models and collapsing old media institutions. Brian did his share of hand holding – certainly with me, hailing as I did from a traditional journalism background at newspapers, the AP and the BBC. It would be no exaggeration to say that Brian rescued me from the analog world, and the dozens of award winning photojournalists, videographers, animators, designers and other professionals I have met through him owe him no less a debt.

Many of us also recall his first office, incongruously located above one of New York’s finest restaurants, the Gramercy Tavern, on 20 th Street. It was actually the apartment he shared with his wife Elodie , whom he had met at Corbis. Many of the same people who learned and benefitted so much from Brian also woke up somewhat polluted after long nights of dorm-style blue sky meetings in the spare bedroom they kept for wayward photojournalists.

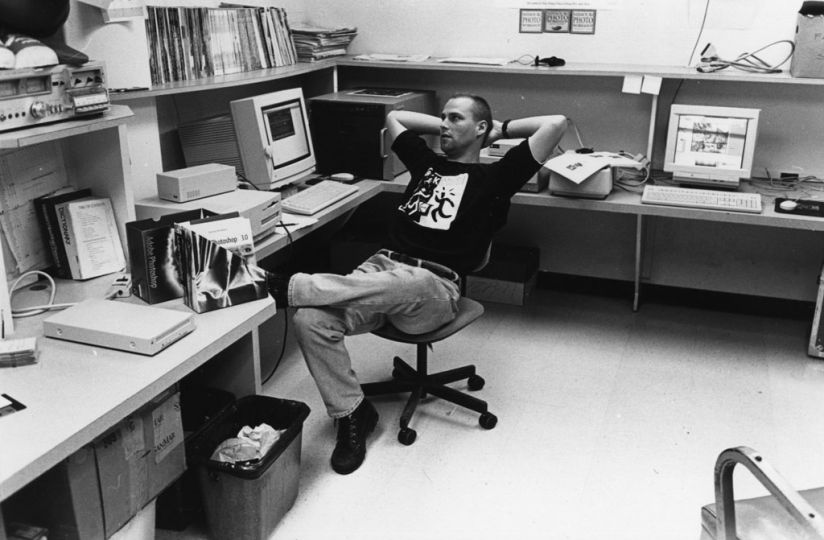

At the center of this success is an uncompromising vision of photography, character and narrative. Early on, at MSNBC.com, Brian built a wing of the newsroom we scribes began referring to as the Death Star – rack upon rack of hard drives and monitors whose myriad uses we could only guess at. His acolytes became “Storm Troopers,” and the zeal with which they pursued a particular style of cropping or editing a photograph was intimidating and a fantastically accurate reflection of Brian himself.

Jeremy Sherlick, who shared in three Emmy Awards with myself and MediaStorm for a series called “ Crisis Guides ” that we produced for the Council on Foreign Relations, often found himself in my office being talked off a window ledge. As the client, Jeremy felt the pressure of deadlines and financial constraints. But he ran into an unremitting demand for excellence in MediaStorm.

“They inspire us to focus on the ancient craft of storytelling,” he said, a novelty for a policy shop like CFR. “They find a way of getting at the heart of every story they tell with the most powerful visuals, the most moving narrative, and the most compelling characters.”

Ed Kashi adds: “Let’s just say that playing basketball with Brian is like working with him. I’d always rather be on his side, let him shoot when he wants to and feed him the ball when he’s open.” I’ve ridden Ed’s advice to success on many, many projects over the past decade. I can’t wait to see what the next ten years will bring.

Michael Moran is an author, documentarian and foreign policy analyst based in New York.

INFORMATION

www.mediastorm.com