Wednesday, January 25, INHA (Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art) packed the Vasari room where the association Profession Photographie organized a conversation with Julien Frydman. Former collaborators, admirers, and those curious hurried to attend this interview, welcoming him with applause as one would a main protagonist, despite his being thirty-five minutes late. All gave clues to the aura of Julien Frydman, who, from Magnum Photo to the LUMA Foundation, revisited his amazing journey, immersed in a theme of renewal.

To start with Julien Frydman commented a picture of himself taken in 2007 firefighting in a Paris street, beautiful image to talk about becoming the director of Magnum photos, Julien Frydman used the same energy and enthusiasm to try to find solutions for the agency, to renew propositions. He tackled the problem of print sales, not previously emphasized, yet still a profit generator. He created the Magnum gallery in order to give a real window front, artistic and commercial, to photographers and photos, starting with Philipp Halsman. During these ten years at Magnum, it was Frydman, magnificently balanced as a tightrope artist, who began to make things take shape. With amazing composure, he turned commercial and financial difficulties into advantages and managed to reinvigorate numbed mechanisms all while respecting the scripture of photography and the freedom of expression that it entailed.

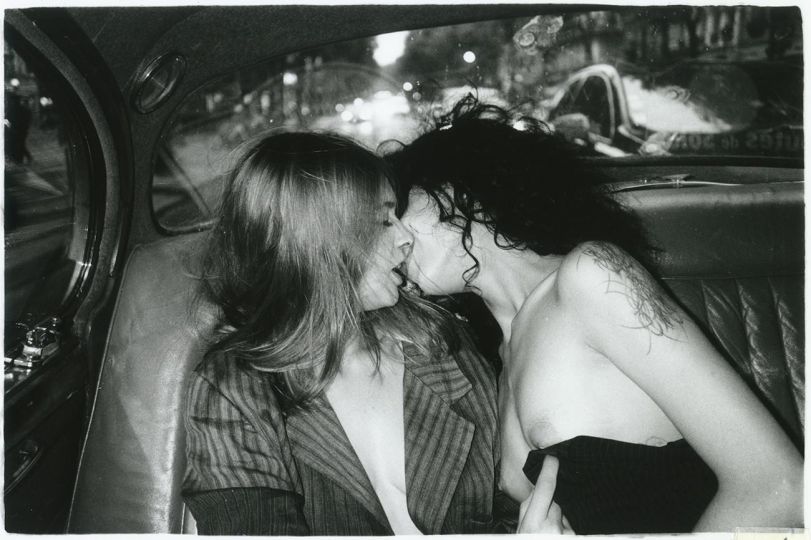

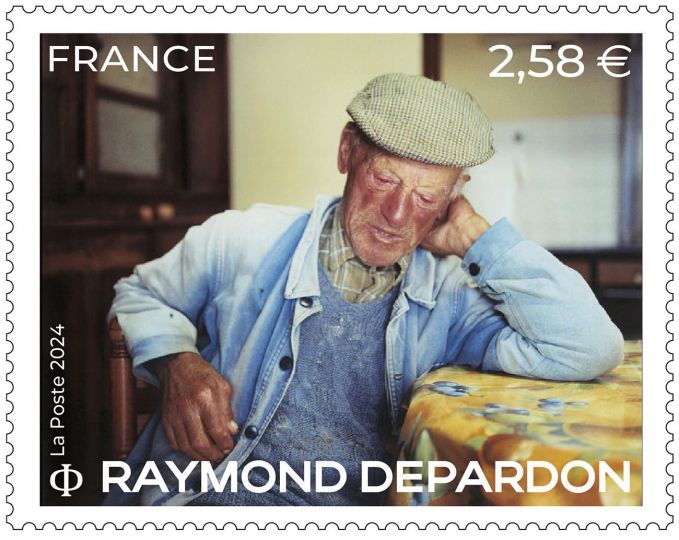

After Magnum, Julien Frydman headed towards Paris Photo with the intention to hold the fair in the 13,000m2 interior of the Grand Palais. The challenge was sizable, but, again, the tight-rope walking Frydman saw beyond financial contingencies and envisioned great artistic and cultural ambitions for this photography-dedicated fair. He wanted to develop a real “programming space”, which would intelligently gather institutions, galleries, collectors, and private partners, forming bridges between the different participants normally honored and treated individually. His talent lies in his ability to break down barriers, to boost the mechanics that mutually encourage one another. Paris Photo was, to him, an incredible land of experimentations. He decided to show recent acquisitions from institutions and reveal private collections to highlight these hidden players and their procurement policies and to put the game of public and private collecting into perspective. The fair’s economy consolidated itself little by little thanks to ambitious partnerships that he developed with some brands. Finally, he put conference cycles in place around photography and photography books, which he particularly loves. Fittingly, he wanted to give a “prominent place to photography books”, and he designated for the editors, previously pushed into a small corner, a dedicated space at the fair. Books being dear to his heart, he who is said to have “done his training in photography” thanks to these books, is why he decided, just like photos, to exhibit them and honor them with the creation of the PhotoBook Awards in partnership with Aperture.

Julien Frydman explained the work he had done on “timing to maintain a level of quality” at Paris Photo. In fact, while in 2011 he tried to convince contemporary art galleries to possibly exhibit their artists “using the photographic medium” (the art of diversion, again!) to “sell by the square meter”, he left in 2014 having doubled business and the number of exhibitors, now selected for the quality of work they were presenting. Described as a tap dancer by some (an honor when you love Fred Astaire!), a derisive nickname for him. It was good to be able to adapt to every situation and to have a high energy level that let him rise to the great adventure of Paris Photo, doubled by his American adventure.

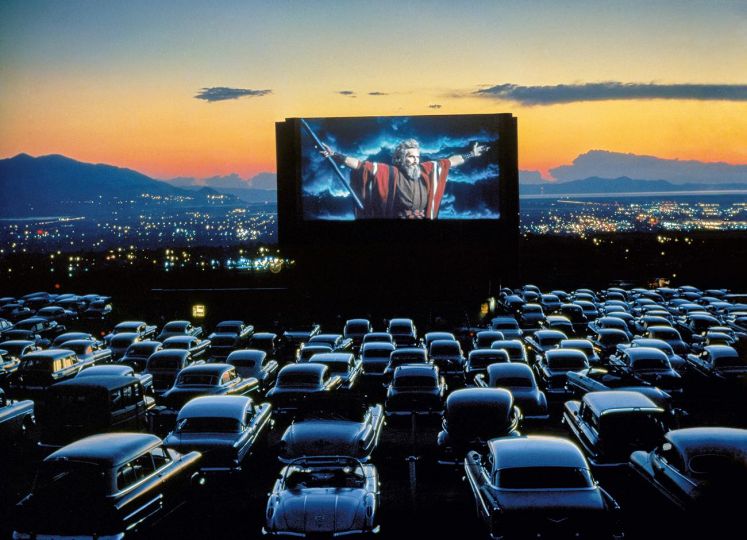

For this American adventure, the first major decision to make was the city, Los Angeles, and the space, Paramount Studios, to succeed in exporting a French fair to the United States. While one would have intuitively favored New York, Julien Frydman chose, strategically and ideologically, L.A. particularly for the history of its “relationship to photography”. It was a completely unashamed relationship, very interesting and waiting to be explored. Paramount turned out to be an extraordinary place to explore exhibition possibilities, with the originality of the space permitting a new way to think about architecture and traditional fair hanging methods. The open perspectives of this new space also let him diversify the content and adapt it to an American context. Blurring the frontiers between reality and fiction, the proposals were just like the ideas of their instigator, exciting and generous. Despite all that, the difficulties of selling to the American public and a low headcount marked Julien Frydman’s departure from Paris Photo and the death of its American edition.

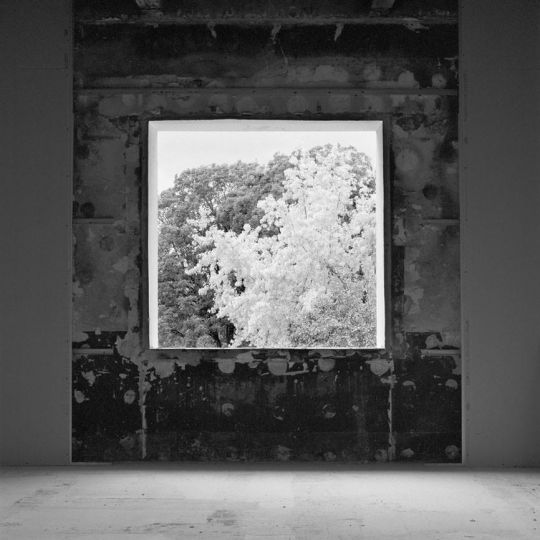

Within the LUMA Foundation, Julien Frydman approaches broader social, environmental, and urban issues, while giving priority to local participants. As always, he does a balancing act to reconcile contingencies incompatible in theory. When one asks him if he is tired of photography, he says no and assures that he can return to it as soon as he wants, at least through the books that he loves. One last statement that truly illustrates the personality and journey of Julien Frydman: consistent, constant renewal.

Anne Laurens

Masters student in Art Market Law, Anne Laurens holds a degree in Art History from Sorbonne University.

Julien Frydman is the Director of Development at the Luma-Arles Foundation.