In late 2015 I was diagnosed with cancer. Before then, I’d not understood how five words could change everything. “I’m sorry, Judith,” my doctor told me, “it’s cancer.” It’s a cliché that you only learn to value life when death is walking beside you, but it was absolutely true for me. I remember driving over Clyde Mountain to bring the word cancer to my parents’ home. Every tree on the range seemed invested with vital force. Every leaf was vibrant, iridescent. Gray mountain gums, in headlights, seemed to manifest ancient intelligence—bearing witness to the fleeting existence of human beings. The threat of death reminds you how precious people are—your oldest friends, children, lovers, parents—you wonder how you’ll bear to leave them. There is a particularly miraculous vision of the world that comes only with the diagnosis of serious illness.

The interval between diagnosis and surgery is an eternity. The surgeon showed me a chart—“If the cancer falls into this range,” he said, “you’ll live; this range and you’ll die.” I felt like Schrödinger’s cat, neither living nor dying. People who see their own death live in two worlds, one mundane and one miraculous. Later, when the cancer had been removed and my death sentence lifted, I watched that other world diminish day by day. No matter how I clung to that miraculous vision, it faded—just as the certain knowledge of my death faded. But something remained. Something is different now—because I know there is a secret world nested inside this one. I’ve seen it.

Years earlier, I’d sat with a friend who was dying of liver cancer. In her last weeks, Marilyn was transformed into a being of another order, into something altogether fey. She saw the world inside the world, just as snakes are said to see ghosts through transparent eyelids. And she told me, “Don’t wait—don’t wait until you’re dying before you learn to see.” Her words returned to me on that night mountain drive: “Don’t wait.” And being a somewhat melodramatic woman—raised on a diet of Christian mysticism and the terror of death—I did the obvious thing and fled into the desert. I don’t know what I expected to find. John the Baptist, perhaps, high on acacia and locusts, flagging a ride from Woomera to Coober Pedy . . . but the urge to run was overwhelming, so I ran.

By this time, I had already made several visits to the Warlpiri people at Lajamanu. Artist and elder Wanta Jampijinpa walked into my Canberra office one day in 2012 and stayed for three years. He had come to the city with an ambition to educate white people (Kardiya) about Warlpiri culture and to instill in them a desire to “care for country.” But many had seen him as a novelty—an anthropological subject or curiosity from Australia’s past. It was optimistic to imagine that urban white culture, with its emphasis on property and security, could be brought into the service of trees, but Wanta tried. When he returned to Lajamanu in 2014, he felt that he had failed to convey Warlpiri values to a single white person. But he was wrong. Because when my world fell apart, and all things suddenly shuddered to life, when trees watched, when blades of grass became unutterably precious and the desert held out its burning arms, the only destination that made any sense to me was Lajamanu.

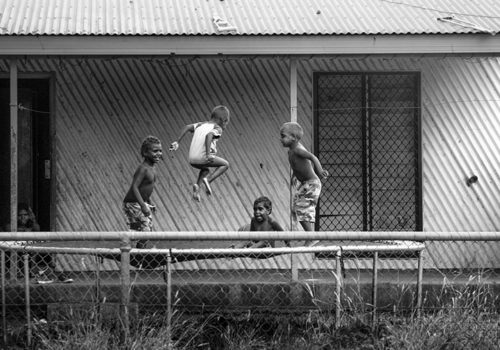

The earliest photographs in this book were taken in 2013, when I still believed the Warlpiri needed my help—to promote literacy and health, to outline positive pathways toward reconciliation, and so on. The later photographs were taken in December 2015, when I knew, without a shadow of doubt, that I was the drowning woman and the Warlpiri were the lifeboat. Lajamanu’s elders, especially Wanta Jampijinpa, Henry Jackamarra, and Jerry Jangala, were kind to me. They gave me a skin name and showed me how to be a “policewoman” for Jdbrille Waterhole. They seemed genuinely delighted by my interest in Warlpiri cosmology, which they illustrated with stories and drawings—some of which are reproduced in this book. The older women took me “hunting” for wattle seed and bush potato. They told me stories of covenants entered into with ancient star-beings and showed me places along the Tanami Track where min-min lights had chased travelers. Fairy tales and mysteries take on new importance when your life feels precarious.

Lajamanu in 2016 is a meeting of two universes. Elders check their Facebook status on iPhones while explaining, in matter-of-fact tones, about a landscape that will hold you or kill you, depending on your scent—where spirit snakes live in the waterways and the dead walk side by side with the living. In Lajamanu I lost my fear of dying, and more importantly, I lost my fear of living. This is a book about magic. Not the magic of Kabbalists, Theosophists, or conjurers, not Crowley’s magick with a k, nor the magic of the New Age or Western religion—but magic that describes the world hidden inside this world, a world seen only by Aboriginal elders and the dying.

This is not a book of photojournalism and makes no attempt to be objective. Quite the contrary, in fact, I wanted this book to be as subjective as possible. These photographs, especially the portraits, have grown out of my love for this community—the poetry of these often physically fragile people, whose unshakable belief in the deep magic of the landscape gives them a strength rarely evident in the city. Warlpiri culture is gentle; it leaves no tracks on the earth. The history of Aboriginal Australia is largely a record of gardening—“cleaning up country” with restick farming and ceremonies to strengthen trees through song. When Warlpiri people move through the landscape, they introduce themselves. They apologize to that country for breaking twigs. They ask permission to take water from the creeks. If humanity ever transcends its selfish and murderous nature, it will be because of people like the Warlpiri.

It was in Lajamanu that I encountered stories of the giant invisible snakes we share the country with. Tales of rainbow snakes, the Warnayarra, underpin all Australian Aboriginal cultures. These early extraterrestrials emerged from meteors at impact sites like Wolfe Creek Crater. They live in the waterways, in rivers and creeks, and the ridges and mountain ranges are records of where they have passed. According to Warlpiri culture, the Warnayarra gave people their language, and they can rise up to protect the country in times of dire need. In the 1950s, when the UK dropped eighteen nuclear and thermonuclear weapons on Maralinga in South Australia, it is said to have been Warnayarra snakes who propelled the atomic cloud back to the military base at Woomera, killing all the children under five. The sentience of landscape is the heart of these Jukurrpa (Dreaming) stories about Warnayarra snakes. My journey began in the center of Australia’s Anglophile government, Canberra, and ended at Wolfe Creek Crater, birthplace of the serpent.

As this book presents some of the views and customs of Warlpiri people, I felt it necessary to get permission from their senior Law man, Jerry Jangala, before publishing the material. Here, and in subsequent places throughout the book, I have presented excerpts from an interview recorded with Jerry on July 27, 2015, at 10:40 a.m. I’ve made no attempt to alter Jerry’s typically Aboriginal use of English, but I’ve translated Warlpiri words where they appear. Jerry refers to me throughout as Nangala, which is my Warlpiri skin name. A recording and transcript of the full interview is available should anyone wish to consult it. Jerry was rather excited about the idea of a book and suggested we might do another in the future. Here are his thoughts on the matter: We can just talk about it like that, but if you make a book here, that’s alright, I can agree with that one. But that book is not for everybody . . . only visit to Warlpiri? Not more yapa? I’d like to see that! Only to the Warlpiri!

That’s alright—that can make a book in the area and story, you know? But I want to do this—Western Warlpiri, South Warlpiri, and North Warlpiri, and East Warlpiri, that too, Warnayaka Ngaliya, it’s like my hand here. You are right with that one, yeah… But I’m thinking about something else like songline, storyline, corroboree line, and all that. Even marriage business, religion, all mix up that one too. Like all stripes, like that, in a way . . . in a way, because we have skin groups real strongly and that little bit mix up, that one.

Judith Crispin

Judith Crispin, The Lumen Seed

Published by Daylight Books

$45