Thirty years since he last exhibited in Paris, the photographer offers us a glimpse behind the scenes of his series Exiles: a visual celebration of the “man with the wind at his heels.”

There is a photograph that came close to never being shared with the public. We owe its presence in this exhibition to the powers of persuasion of the curator, Clément Chéroux, who convinced the photographer to include it in the selection. It shows a hand—Josef Koudelka’s—caressing braids of water streaming from a garden hose. The picture makes it seem like the hand can bend matter, scratching the surface of the world as if leaving its mark. And yet we know it’s just a jet of water that will be gone in the blink of a shutter, as soon as the photographer’s hand withdraws and turns off the valve.

This image best encapsulates Josef Koudelka’s work: all human undertaking is fleeting. Even as it plays with matter, the picture also represents an attempt to capture the void, the limitless, and the intangible; in other words, an attempt to seize life that flows as fast and eludes our grasp as water streaming through one’s fingers.

Hand(s)

Hands are a recurring motif in Exiles. Most famously, there’s the fisted arm with a wristwatch, which opens the exhibition. The arm is raised, as if to see the time, while the deserted Venceslaus Square in Prague stretches out in the background. It’s August 22, 1968. The photograph paradoxically bears witness to a historical moment: Prague residents were going to come together in a massive protest against the Russian invasion. In fact, however, the demonstration was a trap set up by Moscow’s agents; alerted just in time, the citizens of Prague didn’t show up. Josef Koudelka records their absence, the emptiness, and aims his lens at his watch to prove that he was there, at the precise day and time, awaiting what would happen next: presence or absence, entrapment or liberation, history or non-history.

No-time

The fact that he photographed that very hour, and that the picture has been so important to him, tells us a lot about the photographer. Koudelka keeps himself in the margins of history’s apparent landmark events; but he is there when no one else comes. Unlike photojournalists, he doesn’t aim to immortalize timely demonstrations, protests that come down in History. Had he acted like a traditional press photographer, he would have undoubtedly turned his back on this “non-event,” on the empty square where no protester appeared. But he didn’t. Instead, Koudelka saw a fascinating event: an absence that, paradoxically, lends added presence to the people of Prague; precisely through their refusal, through having dodged the trap and the photographer, who, now sidestepped, had become a repository of a time that counts in the history of the country and in the history of the world.

Gypsies

Although he joined the prestigious Magnum agency quite early on, Josef Koudelka has built his career in the margins of, or even in opposition to, the rest of the profession. This contrarianism is Koudelka’s personality in a nutshell. While his fellow photographers take on commissioned work and go on news assignments, he refuses. He photographs solely for his own satisfaction, to fulfill a personal quest, and he won’t let any material constraints get in his way. Having photographed the members of a theatre company back in Czechoslovakia, once he had left the country, Koudelka became interested in nomadic cultures. He followed Gypsies across Europe, observing their way of being, their rituals. As someone who has been uprooted, who has been cut off from his intimates, Koudelka is understandably fascinated by a people with no fixed abode, driven where the wind blows.

Becoming a tramp

What draws him to Gypsies is also the fact that they are a people unlike any other. They are a people of the margins, excluded from the community of sedentary dwellers, and consigned to that community’s outer edges, to a bitter separation. Perhaps Koudelka recognized himself in these qualities. There is no doubt that this way of life, which refuses to call any place home, is very much his own. For over twenty years he livedithout a home base, with no address. A sleeping bag slung across his shoulder, he dilutes his own existence even as he photographs what he does. He leads an ascetic life. He lives on a piece of bread and a glass of milk. Nothing else. He stays with friends, but mostly sleeps under the starry sky, in the fields, by the roadside. He is a nomad, a tramp, rejecting creature comforts which he thinks hinder his perception of things and beings. He is a perpetual exile. As he puts it, “there is no way back from exile” (Josef Koudelka. La Fabrique d’Exils, Xavier Barral 2017).

Evidence

The evidence of his legendary way of life is, for the first time, shared with the public. Following nearly two years of negotiations, as the exhibition’s curator Clément Chéroux attests, Koudelka finally agreed to allow the viewer to go behind the scenes of his work. These are primarily two series of photographs which reveal that his lifestyle is not just a myth. One is composed of self-portraits taken in places where he makes his bed for the night: slipping into his sleeping bag he is stretched on a carpeted floor, in the middle of a desert, outside a building, on a New York rooftop, in an empty alley, on the floor of a friend’s apartment, or on the premises of his photo agency. Koudelka sleeps anywhere and everywhere, because he is fond of “nowhere”—a photographer “with the wind at his heels,” as Clément Chéroux nicely put it.

Timeless material

A particularly moving series complements this evidence: nine photographs of pads that the photographer used as his sleeping mats: a piece of fabric laid out on carpeting, a piece of cardboard on grass, a plain rug on the floorboards of an apartment. What is striking is the impression of emptiness conjured up by the sole presence of such a makeshift mattress. We picture the photographer stretched out on top in the middle of a desert. These make-do accommodations simply celebrate his time on earth. Like a nomadic American Indian Koudelka is an eternal traveler, a vagabond who gleans timeless material from the present moment. Eternity means immortalizing the moment in a photographic image. In order to be a photographer—“to have something to say,” as Koudelka puts it—perhaps he needed to experience extreme vulnerability? Perhaps he needed to worship the ephemeral so as to better capture the backdrop of human existence? “If you suffer more than others, you’ve earned the right to take these photos,” he wrote in his journal in 1974.

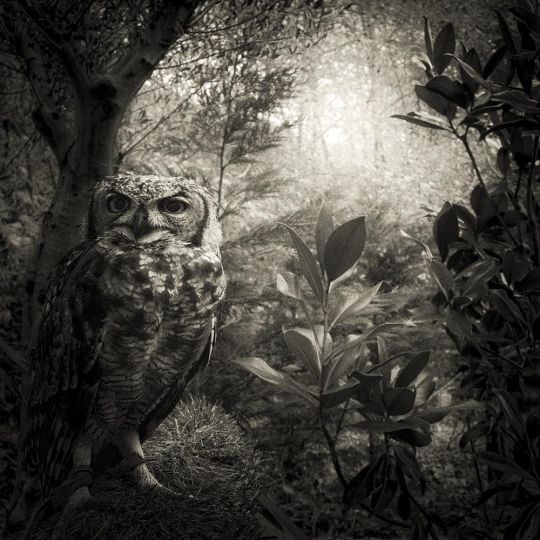

Hence there is also a sense of the tragic which haunts Koudelka’s photographs, with their black-and-white where the light seems to always lose something to the shadows. “Faces never submit completely,” observes Clément Chéroux. Places are transitory, people are vagabonds. Often, there’s no talk, no exchange. People are apart, perhaps, or above all, apart from themselves. This is what the photographs seem to suggest: they portray humanity’s innermost self—our wandering. Koudelka foregrounds the human being pursuing an itinerary, never at peace, restlessly traversing the world in the grips of a deep-seated dilemma: how to be present, how to be alive, and how, at the same time, to accept nothingness, loss, disappearance. How to be oneself.

A flower

One photograph on display at Centre Pompidou says it well. Josef Koudelka was also reluctant to show this one. It represents a young woman on horseback. Up ahead, in the shadow, is a rider wearing a hat. It seems that the horseman is about to snatch the young woman and carry her off to his own land. They could be young lovers; perhaps she is his fiancée. Except that the young woman is not looking in his direction: she has turned to face us, to face the photographer. She looks behind, over her shoulder. Is she contemplating her past? Is she thinking of her youth which is coming to an end as she is about to become a wife and soon a mother? Uncertainty lurks in the corners of her eyes. What is most unsettling in this photograph is that by cutting out the figures, one obtains the contours of a flower. The horse’s tail seems a stem and the young woman’s dress fans out into petals, as if extoling the ephemeral, celebrating fleeting beauty.

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin is a journalist, writer, and stage director. He is a regular contributor to the art journal, pointculture. He lives and works in Paris.

Josef Koudelka, La fabrique d’exils

February 22 to May 22, 2017

Galerie de photographies, Forum-1

Centre Pompidou

Place Georges-Pompidou

75004 Paris

France

Catalogue of the exhibition published by Editions Xavier Barral.