In the laconic world of the vaquero, it’s hard for a while for a visitor to learn much about these tough, independent men. As an old vaquero once told me, “They hired me to push cows; there’s not a lot to talk about.” And, yet, if the visitor is patient and shows an honest respect for the vaquero’s world, his work, his tack, his ethic, the stories start to flow.

When asked if they consider themselves vaqueros, most will say that they are just ranch hands. The term vaquero (literally worker of cows) is a term of respect, and to the vaqueros working today, it refers to their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers who came before them.

Men who really knew how to cowboy. Who knew how to find the hard-headed vacas (cattle) hiding among the mesquite trees, chase them down and rope them and bring them in to join the gathering herd. Men who would stay out two weeks sometimes, sleeping on the ground, rounding up the herd and bringing it in for the branding and shipping, the focal point of the ranching year.

Paulino Silguero, now a remarkable 78, was telling me how a typical day started when he was out on the roundup as a young man. “We’d get up at 4:00 AM and the cook would have break fast for us from the wagon. I’d find my way out to the remuda (roundup horses in a temporary horse corral). All you could see were a few glowing cigarettes moving around. I’d go to where my horses were tied. I had three horses in those days. I’d swing my riata (lariat) in the dark.

The first one I roped, that was the horse I’d ride that day.”

Being a vaquero was and still is a dangerous profession. Steers are strong and unruly, the brush is full of sharp thorns, pests are in the air, and the summers are punishingly hot. Máximo Cremar, now in his 70’s, had his thumb popped off when his riata twisted around it as he roped a bull. Riding a horse is perilous. As my friend Felix Serna of La Paloma Vieja says, “Cuando pones la pata en el estribo, no sabes como vas a venir para atrás (When you put your foot in the stirrup, you don’t know how you’ll come back).”

Vaqueros were here in Texas before there was a Texas. They had migrated north out of Mexico with the huge Spanish land grant ranches. Their knowledge of horse and cattle handling was indispensable on the ranchos. Their knowledge came from the Spanish, but they refined and honed their skills to better fit the rugged South Texas brush. When men such as Captain Richard King, Mifflin Kennedy and Captain James Armstrong came to Texas and started buying the Spanish land grants, they naturally turned to the vaqueros already there to help them start their cattle empires.

The fact is, the vaquero was the first cowboy. Another fact is that the vaquero taught the Anglo cowboy everything he needed to know. Just consider the Spanish terms that have found their way into the lingo of the cowboy and the West: vaquero became buckaroo, bandana (large, colorful handkerchief), vamoose from vámonos (let’s go), sombrero, botas (boots), chivarras or chaparreras (chaps), riendas (reins), montura (saddle), espuelas (spurs) and so on. And, while most vaqueros are Mexican-American, it is important to remember that there are also Anglo and black vaqueros, men who represent many generations on the great ranches. There are also names such as Máximo Cremar and Adolfo Brady, testifying to the intermarriage of those with Mexican and Anglo forebears. My good friend Daniel Boone, caporal (foreman) of the San Pedro Ranch, with sangre de México (Mexican blood), traces his lineage, in part, to the original Daniel Boone.

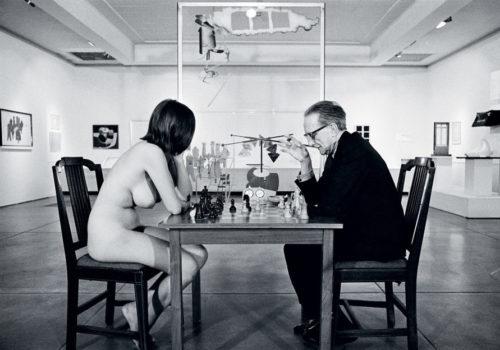

I am fascinated by photographing what is real. Not trying to manipulate and mold it into some- thing it’s not … something I think it ought to be. The vaqueros’ world is real. These men still practice 19th century skills, and it’s important that they be expert at these skills or they’re out of a job. So, for me, photographing this wonderful, fascinating world is a dream come true. My background is commercial photography, a discipline that is all about artifice. The commercial photographer is hired to make the subject, whatever it is, look like it should look, not how it really looks. That’s advertising.

But, it would have been a fatal mistake to start the vaquero project with a preconceived notion of how this world should look. It would have been an easy trap. We all have a dreamy, romantic idea of what the West was like and about life on a big cattle ranch. Our mental pictures come from the movies and from paintings and photographs made over the years that collectively created an idea of how the cowboy life should look.

I was determined to do two things: photograph the vaquero life as it is today without gloss or retouch, and make photographs that didn’t repeat the beautiful clichés that we’ve all seen over and over. The latter was hard to keep from doing. The vaquero subject matter is so compelling, so interesting, so important culturally, I had to stop myself more than once from looking for those images we have all seen a million times. But, in truth, seeing and photographing what is there, right now, is far more interesting than shooting the cliché.

I chose to shoot B&W (black and white) on purpose. Not so much because it is more “artsy.” I’ve never subscribed to that view. But, because B&W is more honest and makes me, as a photographer, work harder. It’s easy to justify a photograph because of the play of color in it: red barn against a green field, for example. But, you realize the photo is about red and green going together, not the subject. Take away the color and you have a boring photograph.

Photographing the world of the vaquero is all about being honest. To them and to myself. Lionel Sosa and I set out to tell the story of the vaquero. But, of course, that’s impossible. It would take a book of 1,000 pages to tell the story. Instead, we decided to produce a kind of “ode” to the vaquero. We try to build an impression of the vaquero’s world with beautiful images.

Mary Margaret McAllen quoted her father when I called to tell her what we were doing: “You’re 30 years too late.” He was right. But he was also wrong. There is still enough of the story left to tell. Sure, the big ranches don’t have 30-40 vaqueros living and working on them anymore.

Much of the herding is done by helicopter. The modern vaquero spends a lot of time “taming” the cattle so they are easier to round up and work and ship; as a result, they are less stressed in the process. There aren’t many papalotes (windmills) left for them to service. But, they still have to “know” cattle and horses … how to spot a sick animal and what to do about it. How to throw the beautiful riata and rope an unruly steer. And, how to ride. Oh, my, how they do ride! The skills of the vaquero are still celebrated and practiced, both on and off the ranch. Nearly every weekend in ranching country there is a small “ranch rodeo” or roping event where the vaqueros (and now hobbyists, too) get together and pit themselves one-on-one against the clock in “heading and heeling” steers, branding, milking wild cows, and more. In the 21st century, it’s hard to think of another occupation that depends on 19th century skills, largely unchanged, to do the job.

The vaqueros and ranchers will tell you that times are different now. It’s not like the old days. There are fewer vaqueros and fewer jobs for them to do. I suppose the time may come when we’ll have only memories of the vaquero. Along with the cattle industry as a whole, this life is vanishing into the pages of history.

So far, the vaquero’s story has gone pretty much untold. But, this book is an attempt to do something about that. To shine the light of recognition and honor on these important men. And their wives and children. They represent an extended community of hard work, honor, sacrifice, pride and humility that is hard to match elsewhere. Some day they will be gone, but their legacy will continue.

These photos and essay are from the book, “El Vaquero Real, the Original American Cowboy”

John Dyer chez Heidi Vaughn Fine Art