For the past five decades, the American photographer Joel Meyerowitz has roamed the streets of the world, countrysides and beaches in search of life in blue, green, yellow and red. In the 1970s, his sense of modernism contributed to accept color photographs as works of art.

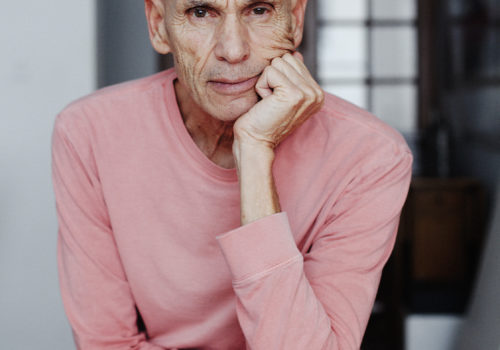

Good photographs are reflections of the soul of their creator. The photographs of Joel Meyerowitz are a blend of softness and serenity—two character traits that not even the wailing sirens that deafen New York’s Upper West Side were able to disturb on a recent visit. Sitting calmly amidst shelves containing fifty years of pictures, Meyerowitz, now in his seventies, opened the book containing his life’s work and spoke fondly about it, as a grandfather of photography.

In 1962, Joel Meyerowitz was working as an artistic director for a small advertising agency that used photography more as a commercial tool than anything else. But this is also where he made the acquaintance of Robert Frank, who had been hired for a one-day session. This encounter triggered something, even if Frank would never, strictly speaking, be his mentor. “He was a real loner. Sometimes when I ran into him he would send me away.” Inspired by The Americans, Frank’s cult portrayal of a money-driven United States, Meyerowitz hit the streets for the first time. He was 24 and only knew one thing for certain: a good photograph isn’t necessarily posed for. “The best way,” he says, “is to look at the ‘old guys’ like Brassaï and Atget. The street teaches you to act quickly when you see something. If you don’t, you miss it!”

For fifteen years, he spent his life on sidewalks, in restaurants, parking lots and subway stations, day and night, rain or shine. With the sharp eye and quick fingers that only real photo lovers know, he juggled men and the objects surrounding them, letting one provide context for the other. Above all, he captured those “decisive moments” so dear to Henri Cartier-Bresson. In one scene in Paris, a man is lying on the ground as another man with a hammer steps over his fallen body, all while a curious crowd looks on. In New York, surrounded by buildings, a woman seems to want to to escape a man’s grasp as he holds her by the arm. These precocious photographs—his “baby pictures”—show the promise of Meyerowitz’s talent.

Complex Photographs in Color

“In basketball,” he explains, “when you start getting good, you know how to handle the ball and play the game. You keep playing until you reach a certain level. Street photography is the same. I got to the point where I knew how to be in the right spot, at the right time, at the right distance and—click—the photo turns out right. But then I asked myself: is that all there is to it? Is that all photography has to say?” After having perfectly emulated his illustrious predecessors, Meyerowitz went deeper, taking street pictures that were more dense and complex, composed of several different moments. In these images, there is not one single event; it almost looks as though they were superimposed, like in this photograph with two men exchanging a ticket, another smoking a cigar, and then a third whose face is in the shadows, with a mysterious hand reaching out of a telephone booth. This is proof that street photography is a multidisciplinary art. The style is similar to photographers from a later generation, Alex Webb or Julie Blackmon, only her compositions are artificial.

For Meyerowitz, the street is an affair of the heart. He prefers to see it as it appears to him: in color. “There’s a desire for the real world, for the meaning of the time in which we live.” While moving towards a more sophisticated mode of expression, he simplified the way photography is perceived, refusing to accept that the world should only be seen in black and white. In 1966, Meyerowitz armed himself with two rangefinder Leicas, one with color film and the other with black and white, then took two near-identical photographs of the same scenes. The result, surprising for its clairvoyance, will soon be available in a small book, The Question of Color, published in the middle of the limited edition one by Phaidon.

“See how boring grays are! In color, there’s red, green, blue, silver—the images is alive. It’s striking. Why would I want to speak with a gag in my mouth? For me, color is like stereo sound. Black and white is a reduction. That doesn’t mean it’s inferior, it’s just different, more formal. It’s good for shadows, silhouettes and contrasts.” Coming to the conclusion that his role as a young man was to “pit [himself] against the establishment,” Meyerowitz became a champion of color. By the 1970s, he had prevailed: magazines switched entirely to color, and galleries started buying color photography.

More delicate and exacting, reportage photography has never been an art world favorite, a fact which baffles Meyerowitz. “It’s still misunderstood and hard to sell. A collector prefers to see the face of a celebrity or a decorative image. And yet, people like Alex Webb and Bruce Davidson are experts when it comes to vision. There’s still a large disparity in the price of a photograph and its value.”

From Small to Large Format

The essence of the artist is to never be satisfied. In 1976, feeling a little restricted, Meyerowitz tried working in a larger format and decided to make a radical change in his subjects, leaving humans out of the picture altogether. In the following years, he developed a passion for more spacious images: landscapes, atmospheres, and shots of architecture. “I wanted to see in the dark, and at the time it wasn’t possible with a small-format camera. You needed really sensitive film and a slow exposure.” He printed his photographs in the correct proportions. The images were rather decorative, but they reflected an awaking of the senses, showing the nature and beauty of a world without man.

On the beaches of the east coast, Meyerowitz returned now and again to his first love: posed portraits. Over the course of four years, he photographed swimmers, including a few teenagers who appear in a series strangely reminiscent of the contemporary photographer Rineke Dijkstra. “I exhibited these photographs in 1983 in Amsterdam,” he says. “I”m not saying they were an inspiration for her, but these photographs were out there. At the time, color portraits weren’t very welcome in galleries or museums.”

Meyerowitz managed to find these people, these “strangers” (as one New York gallery owner disdainfully put it), just about everywhere, from the beach to their own houses. He invited them to his place to take their picture. They were friends and family and people he met by chance, but he would also put ads in the local newspaper that read: “REMARKABLE PEOPLE! If you think you are remarkable or think someone else is, Joel Meyerowitz wants to take your portrait. ” He photographed members of his family in the mountains and assembled a photograph from three different scenes. The subtlety of the montage is difficult to detect at first glance. (It could easily have been featured at the Metropolitan Museum’s recent exhibition, Faking It.) “That was a little change. I had to tell people what to do. I was still a street photographer at heart, and on the street you don’t say anything, you just watch.”

Meyerowitz’s personal history has been full of questions, never more than when two airplanes changed the world on September 2001. Afterward, he was given a police badge and became the sole photographer to document the nine-month clean-up effort at Ground Zero. Many questions remain, but the most insistent one is existential: “Is it true, the way I see things? Do I represent the world the right way? As an artist, more than anything else, one is always looking for one’s identity. I’m not talking about fingerprints,” he jokes, “but your identity as a human being. Photography teaches you who you are.”

Joel Meyerowitz was very young when he realized that his photographs were also priceless historical documents: a record of our lifestyles, our behaviors, tastes and styles. In addition to the beautiful book from Phaidon, his work will be the subject of a major two-part exhibition at the Howard Greenberg gallery, beginning today and lasting until early January. The answers to some of those questions may be found here, amidst some of the most beautiful images in the history of street photography, generously offering themselves to a new generations of photographers . Here’s hoping they keep the tradition of street photography alive.

Jonas Cuénin

Some quotations attributed to Joel Meyerowitz in this article have been back-translated into English from the French, and do not necessarily represent his actual words.

Joël Meyerowitz

Exhibition :

Part 1 : November 2 – December 1, 2012

Part 2 : December 7, 2012 – January 5, 2013

Howard Greenberg Gallery

41 East 57th Street

New York

(212) 334-0010

Book:

Joel Meyerowitz: Taking My Time

Phaidon, November 1st, 2012

$750, limited edition