Costume. How we define ourselves when we stand upon the world’s stage and read from the scripts we draft. In donning an ensemble, we assume a posture, an attitude, an aesthetic that we accept as how we see ourselves, and how we wish to be seen. Costume can shape identity the way the corset shapes a woman’s waist. It can take hold and command a sense of respect, of pride, and of purpose, and in this way it can become the most subversive thing on earth.

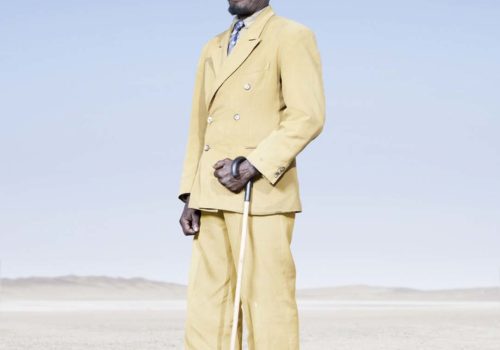

This is evidenced in Jim Naughten’s new series of photographs collected in Conflict and Costume: The Herero Tribe of Namibia, both a book published by Merrell and an exhibition at Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn that opens March 14 and runs through May 4. In Naughten’s photographs, the Herero stand tall against a blue sky, radiant like flowers blooming across the desert floor. They are garbed in fine style, a look the world has never seen, a post-colonial aesthetic that commands authority as it illustrates the defiant spirit of the Herero peoples.

The Herero arrived in Namibia in the eighteenth century, bringing with them horses, ox-drawn wagons, guns, and Christianity. As Lutz Marten writes in the introduction to Conflict and Costume, “They also brought new styles of clothing, and it was during these early days of contact with the wider world that the Herero were first introduced to the military uniforms and Victorian-style dress.” As their economy developed, the Herero took to sartorial expression of their success.

In 1884, Namibia was annexed by the Germans to forestall British encroachment. The Germans, however, made for cruel rulers, with their brutally enforced notions of racial supremacy, alternately slaughtering or enslaving the populace. The Herero resistance led to a full-scale war from 1904-08. About 80% of the population was killed. In 1915, the German colonial army was defeated by South African forces, which then annexed the country until 1988. But it was the brutal war against the Germans that became central to the rebuilding of the Herero cultural identity.

Shortly after the end of World War I, the Herero created the Otruppe, a symbolic, rather than actual army. From the uniforms of the killed or departed Germans, a regiment was born, and women joined in creating grand dame gowns that befit the most regal ladies in the world. The Herero have created a highly detailed and symbolic form of costuming for the regiments, which are donned at ceremonies and festivals to commemorate the past that take on a level of radical chic. “To the victor go spoils,” it has been said. To assume the costume of the enemy in memory of those who gave their life is nothing short of a kind of victory that few could ever imagine.

As Naughten observes, “Namibia is an extraordinary country, and perhaps most interesting to me is the stories that we don’t know, the ones that have been lost or fragmented in aural tradition. There’s very little literature from the last hundred years or so, but there’s a tangible sense of history in the ghost towns, colonial architecture, cave paintings, and the landscape that feels otherworldly and timeless.

“When I look at the dresses and costumes I see a direct connection of this period with an almost ghostly imprint of the German settlers. I see my images as both a study of and a celebration of the costume, and not as a formal documentary on Herero culture, and the paradoxical nature of the story is one of the most interesting aspects. Why would the Herero adopt the cloths of the very people who cost them so dearly?

“I see the clothes as symbolic of survival and strength, but particularly of a kind of defiance. In that sense, they are heroic. The taking and wearing of their enemies clothing is considered a way of absorbing and diminishing their power. They march and drill after the German fashion of the period, and ride horseback with extraordinary skill (horses were introduced by the settlers). To me the Herero are undiminished and have an extraordinary grace and presence.”

Naughten’s portraits are as majestic as the people he photographs, imparting a feeling of beauty and power that many in the West rarely consider when they think of Africa today. Naughten’s photographs of the Herero show us what victory truly means, and how it is that every day we walk this earth, we honor those who came before us, embracing the good, the bad, and the ugly on mankind and transforming it into a symbol of cultural and personal pride.

Miss Rosen