11 years ago, Dina Goldstein created her series In The Dollhouse, in which she questioned the Barbie phenomenon. a few days before the release of the Barbie movie, we are republishing the text from Barry Dumka.

Dina Goldstein’s In The Dollhouse and the Perils of Plastic Perfection

Since her 1959 debut wearing stilettos and a zebra print bikini to the tagline, “a shapely teenage fashion model” and theme song Barbie You’re Beautiful, Barbara Millicent Roberts has been a lightning rod for debate about the socio-cultural expectations for female identity. She certainly looked different from the typical baby-faced dolls of

her day. Tall, thin, golden-haired and glossily made up, Barbie was modeled after Lilli, a curvy sexualised doll sold in

German bars to adult men based on a racy comic strip character. Equally as buxom, Barbie expressed her through her body image, wardrobe and lifestyle. Acquisitive and carefree, Barbie is the glamour girl of a mythic America where being perfect, popular and plastic is the highest ideal. As a corporate-sponsored American princess, Barbie was made to live the dream of a good life.

That’s not Barbie’s fate in Dina Goldstein’s hands.

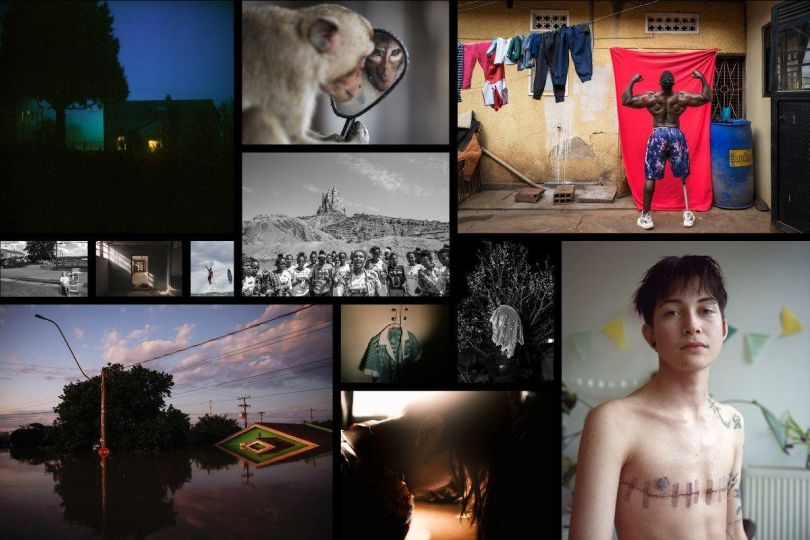

For her second conceptual series of large-format photographic tableaus, Goldstein subverts the storybook storyline of Barbie and her blow-dried boyfriend Ken. Using the sequential narrative form common to comic books, Goldstein places the long-time couple in a custom-manufactured alternative reality of her own design and decoration. A pink on pink playhouse that seems sweetly perfumed for romance. Even the pillows insist on love.

But the candy-coloured interiors and playful appeal of the iconic dolls are Goldstein’s Pop Surrealist lure to engage an audience about serious issues. In The Dollhouse is social documentary photography masquerading as a puppet show. The series of 10 panels unfolds a tragicomic tale of the perils of being plastic and the potential for salvation through authenticity. Barbie gets the short end of that stick – in Goldstein’s telling of her story, she endures psychological dysfunction, an emotional breakdown, a really bad haircut and, ultimately, decapitation.

Life wasn’t supposed to be this hard for Barbie.

Shaped into Barbie’s form – and all her fabulous clothes – is the cultural expectation that her life is charmed. She is the ultimate material girl meant to have it all – iconic beauty, gravity-defying breasts, salon-perfect hair, wafer-thin waistline, any job that she wants and a boyfriend content to live in her shadow for more than 50 years. From her proportions to her wardrobe, Barbie sets an impossible standard for girls and the grown women they become.

With over a billion sold and the average girl owning at least 8 Barbies, developmental psychologists indicate the dolls plays an active role in shaping a young girl’s self-image. Arguably, Barbie’s a tool in the hand teaching females that appearance and material possessions matter for achieving social status. And, possibly, a gateway drug to a

lifelong obsession over what it takes to fit the ideal of feminine beauty.

Dina Goldstein’s photography projects have made her an iconoclast in fantasyland. Her acclaimed series Fallen Princesses recontextualized Disnified heroines to engage awareness about societal challenges: pollution, war, obesity, marital dysfunction. As with In The Dollhouse, Goldstein draws from her earlier photodocumentary work

and her keen ability to find the fragmented truth in a story no matter the scene. Goldstein’s scenes are no longer happened upon but diligently arranged though the artifice is still meant to be cut from the coarse cloth of social reality. As a surrealist, Goldstein knows that beneath the smooth, polished surface of our pop cultural age, the

truth is writhing to be set free. Her work is intended to – and does – provoke debate. It’s intentionally theatrical but

has an honest message. Every image is queerly compelling. Still, the comedy and charm of In The Dollhouse can’t be denied. Goldstein has set an immaculate scene and found

the cast to match it. There is an overlay of 1950s ornamentation and respectability in the setting: the French Provincial furniture package, fine china tea service, Barbie’s well-coiffed hair and taffeta dress, Ken’s sweater dashed about his shoulders. Everything is in its proper order – well, almost.

Bored and oblivious, Barbie is about to have her perfect life tripped up by the bold gay kick of Ken’s pink pump. If Oprah didn’t give away his secret, the bleached-out dude doll just getting out of bed with Ken definitely subverts the couple’s corporate marketing story. Admittedly, Ken has always been subject to rumours. When Mattel issued

Magic Earring Ken in 1993 – complete with buff body, mesh tanktop, mauve vest and a much speculated upon

chrome ring about his neck – the doll sparked controversy and was soon discontinued and recalled despite its popularity. Twenty years on, in Goldstein’s fantasia, Ken is more carefree and happy to lead his life as he chooses.

It’s Barbie who struggles with her identity. As the power of her synthetic perfection proves worthless, Barbie ends up broken in the corner. Just another doll, headless and forgotten. The final panel of In The Dollhouse is shocking but the penultimate one more sensitively links Goldstein’s artistic efforts to a bigger purpose. The socially-constructed expression of female identity, beauty and individuality is, of course, much older than ageless Barbie. In The Dollhouse contains a bonding moment with Frida Kahlo, the Mexican artist known for her fierce and wounded self-portraits – as well as her tempestuous relationship with the frequently unfaithful Diego Rivera. Kahlo endured great pain throughout her life, both physical and emotional, and poured that hurt and heartache into her paintings. Watched by a voyeuristic eye peering through the back window, Goldstein’s The Haircut recreates Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair – both women pictured are shorn of their long locks and wearing a man’s suit. The visual conversation between these two provocative female artists – creative girl talk – is raw and poignant and sly. The “proper” role of women in society and how to fit their frame to that prescribed form becomes for Goldstein, as much as Kahlo, the motivation for her metaphorically surreal imagery. Goldstein shows the price that women pay trying to be perfect.

A relational postscript to In The Dollhouse is the real life hardships endured by the people who made or inspired Barbie and Ken. Ruth Handler, the Mattel President who came up with the idea for Barbie, was diagnosed in the 1970s with breast cancer and underwent a radical mastectomy. Jack Ryan, the chief engineer who shaped the look of Barbie, was a six-times married hypersexual swinger known for hosting wild orgies in his lavish Bel Air home; he suffered from alcoholism and took his own life in 1994 (writing “I love you” on the bathroom mirror using his last wife’s lipstick). The real life Ken, son of Ruth Handler, hated being associated with his namesake doll; though

married, he was a closeted gay man and died in 1994 from an AIDS-related complication. Barbara Handler, or Barbie, also shuns the association; after her divorce and various cosmetic surgeries, she lives as a recluse in Southern California.

Such are the truths of regular life. Nothing is plastic coated. The human condition existing in the real world is complicated and lacks the fantastical powers required to make a life perfect. Still, there can be beauty despite the flaws. In Goldstein’s visual narrative, Ken embraces his particular kinks and is liberated. Barbie – stubbornly and

stylishly conservative – is destroyed. But maybe the scene in Goldstein’s last panel is transitional, not final. Dolls are resilient. They can take a beating and then snap their heads back on and begin the game again. Goldstein’s In The Dollhouse plays with our narrative expectations as well as our cultural ones. In the toybox of social popularity, can our culture love a Buzzcut Barbie? Who will play with her now?