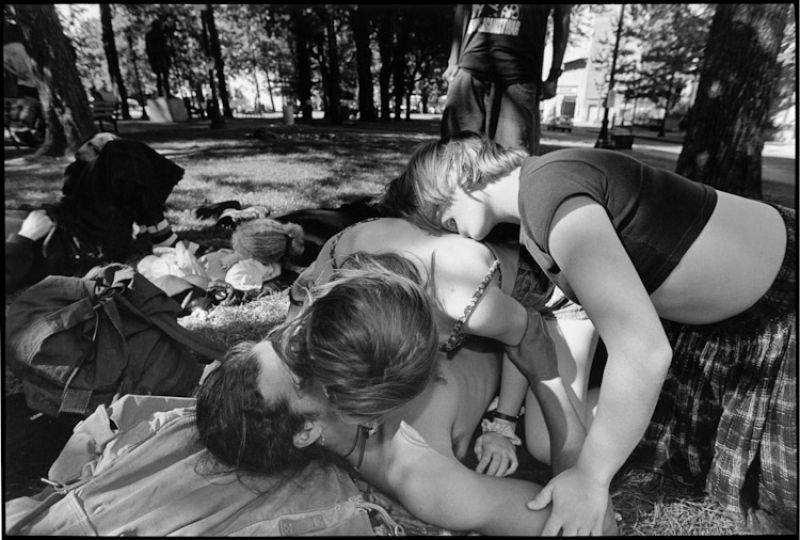

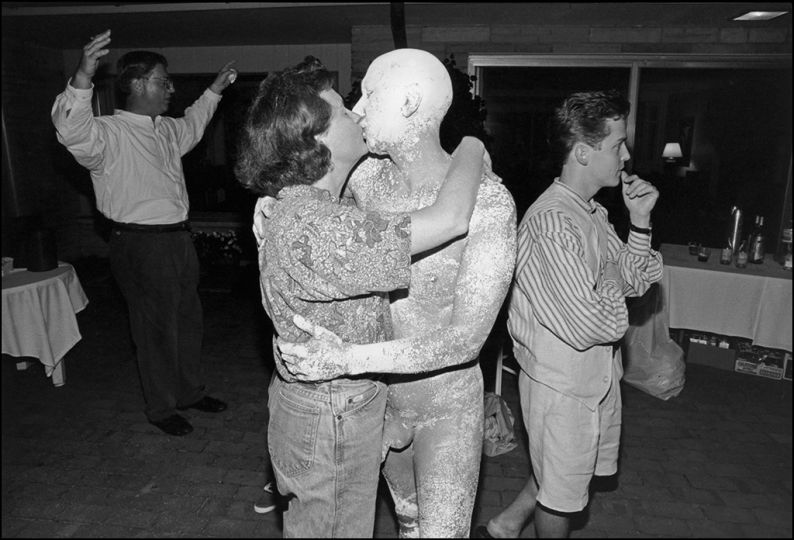

Since I was five years old, I have been photographically curious about the people, places and events in my life. As I became older, I took photographs of my family, friends, relatives, celebrations and losses that became reminders of my personal history. Eventually, I decided to dedicate my life to documentary photography and understood that, as a maker of pictures, I was in the memory business.

The photographs in my archive and on my website tell the tale of a life. They are autobiographical. They are personal and diaristic. They are full of emotion. Some are humorous. Others, such as those from “12 Nazi Concentration Camps,” are confrontational, disturbing, unpredictable and grounded in our collective memory (yours and mine).

The photographs I made at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Flossenbürg, Fort Breendonck, Majdanek, Mauthausen, Natzweiler-Struthof, Theresienstadt and Treblinka from 1981 to 1983 are counterpoints to the historical and contemporary photographs of the camps made at the end of and after the war by a number of photographers, including Margaret Bourke-White, George Rodger and Erich Hartmann. My pictures were created in color with a cumbersome 8” x 10” field camera; the historical and contemporary photographs by other photographers were made with smaller, more portable cameras using black-and-white film.

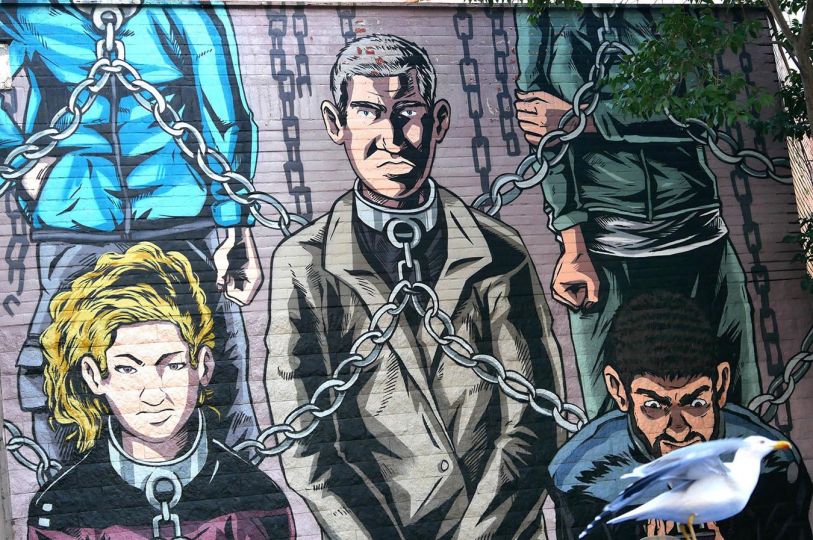

The expectation on the part of many viewers is that contemporary photographs of Nazi concentration camps should be in black and white and devoid of people or any reference to the contemporary world. My color photographs include self-portraits, tourists and survivors and have inspired visceral responses in many viewers. During a lecture I presented at the International Center of Photography in New York, an enraged audience member screamed, “You can’t photograph Nazi concentration camps in color, on sunny days. Don’t you know that the Holocaust happened in black and white? There weren’t any deep blue skies or puffy white clouds during the Holocaust. What’s wrong with you? How could you take pictures like that?” Another member of the audience jumped out of her chair and vehemently disagreed with the remarks – and a heated argument ensued between them and others who joined in before ICP Director Cornell Capa defused the conflict. My color photographs in “12 Nazi Concentration Camps” exist in stark contrast to the historical black-and-white photographic record of Holocaust images that are the basis for most viewers’ knowledge and understanding of the Nazi era and may present a challenge to their long-held perceptions.

Presenting Nazi concentration camps in color is unprecedented. For the first time, photographs of concentration camps are brazenly passionate and “hot,” rather than detached and “cool.” There have been no other photographs of these sites created that look like the ones in this series. These photographs are visual memoirs that document a psychically perilous journey through six countries and twelve sites and reveal a malevolence that is not frozen in time or removed from our modern lives but, rather, is still palpable forty years after the Holocaust ended. The pictures are, inscrutably, both objective and subjective. They are against the grain, self-reflexive and idiosyncratic in breaking new ground in the medium, while at the same time acknowledging the tradition of documentary photography. The photographs of the camps in Eastern Europe also reflect a Communist epoch now extinguished.

I intended these photographs to be audacious and surprising and, ultimately, impossible to forget. I hope they will challenge viewers’ ideas about the camps and what happened there by presenting the past and present simultaneously.