In Irving Penn’s work a whole century unfolds before our eyes, transformed by the eye of the master. Whether he photographed the Mud Men in New Guinea, or a painter, a writer, a boxer, a movie star, or cigarette butts, or a bowlful of bouillabaisse in Barcelona, he goes beyond appearances. He is an entomologist who captures the essence of things and beings. His exploration of light seems to stop time in its tracks. His vision of the world has left a mark on fashion and advertising alike, and is firmly inscribed in the history of art. A superb retrospective paying homage to the photographer is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It’s a monument to the immortalized glory of the ephemeral.

“I don’t photograph what I see. That’s not what interests me. I photograph only what I find intriguing.” Irving Penn uttered these words one autumn evening in 1991, when we met in New York. From the start, he set the tone. Irving Penn was at the time among the most demanding, if not the most tormented, contemporary photographers and a great perfectionist. The current retrospective of his work at the Metropolitan Museum in New York is undoubtedly the most comprehensive ever assembled. The catalogue totals 372 pages and 365 photographs, and retraces the oeuvre of one of the greatest photographers of the last century.

Irving Penn is a unique character in photography. He lived far away from the hustle and bustle of New York, in the seclusion of his Long Island country home. Two or three times a week, he would come to his studio on Lower Fifth Avenue — “the hospital,” as it was called by his assistants and fashion editors. For thirty years, he reigned in his office with unwavering diligence and scrupulousness, sometimes in complete silence, re-photographing a single image ad infinitum, until it was absolutely perfect. From time to time, he would be accompanied by the beautiful Lisa Fonssagrives, his wife of forty years and one of the top models in the 1950s, whom he discovered on the set of one of his photos and with whom he fell in love head over heels. They were married three years later, in 1950, and had a son, Tom. Once a photo shoot was over, they would return to their farm where all Lisa ever grew was flowers. Occasionally, would Penn linger in the office and, which was a great honor, invite a visitor for a sandwich or some pastries, which he adored. Nothing interested Penn more than the still image. He became a photographer the way a convert joins a new religion. He zealously assimilated all its dogmas, and it was not uncustomary for him to lock himself for days on end in the lab to perfect his famous platinum prints.

Irving Penn was born on June 16, 1917, almost exactly a hundred years ago, in Plainsfield, NJ. As a child, he never spoke. When he was five, his baby brother Arthur, who would become a filmmaker, was born. Irving studied design with Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary guru of the history of photography. Using the money earned from the first sales of his sketches, Penn bought a Rolleiflex, but continued to be obsessed with painting. In 1942, he went to Mexico to paint and draw. Upon his return, he destroyed all his works. He enlisted in the army, and served a tour in Italy and India. Back in New York, he became an assistant to Alexander Lieberman, the director of Vogue. This was the beginning of a long, intimate, and steadfast friendship that tied them for life. Penn was tasked with designing magazine covers. Following Liberman’s advice, one day he began photographing his projects. And thus a photographer was born.

In 1947, Vogue sent Irving Penn to Milan, Naples, and Rome to shoot all the big names in the world of Italian arts and letters. To help him in this war-ravaged country, Edmonde Charles-Roux, a young woman editor-in-chief of the French edition of Vogue, was assigned to him as a guide. The journey lasted three weeks. For Edmonde Charles-Roux, this was an epiphany: “Penn made some fifty incredible portraits. He had everything under control. He didn’t miss a wink, smile, or grimace of his model. He was in a state of permanent trance.” Edmonde Charles-Roux met him again a year later, in Paris, when he was working on the famous series on small trades. Fascinated by the innumerable street vendors after the war, Penn rented a studio at the school of photography in Rue de Vaugirard. But he ran into a problem: his own shyness and the language barrier made it impossible for him to find his own models. Who could help him out? Robert Doisneau and his accomplice, Robert Giraud, took on the task. For a month, Doisneau and Giraud drove around the streets of Paris in a sumptuous Packard, snatching and chauffeuring a scissor grinder, a balloon saleswoman, or some chimneysweeps… Doisneau would later recall: “It was amazing to watch the encounter between this American in a trance and disconcerted Parisians. He would stare at them intently. They were petrified. Without saying a word, he would pose them and then rush to his camera. There was a metallic eyecup over the viewfinder: invariably, his eyebrows would be bleeding after a daylong session. Beautiful moments, beautiful memories of this extraordinary gentleman, who, by the way, was kind to a fault.”

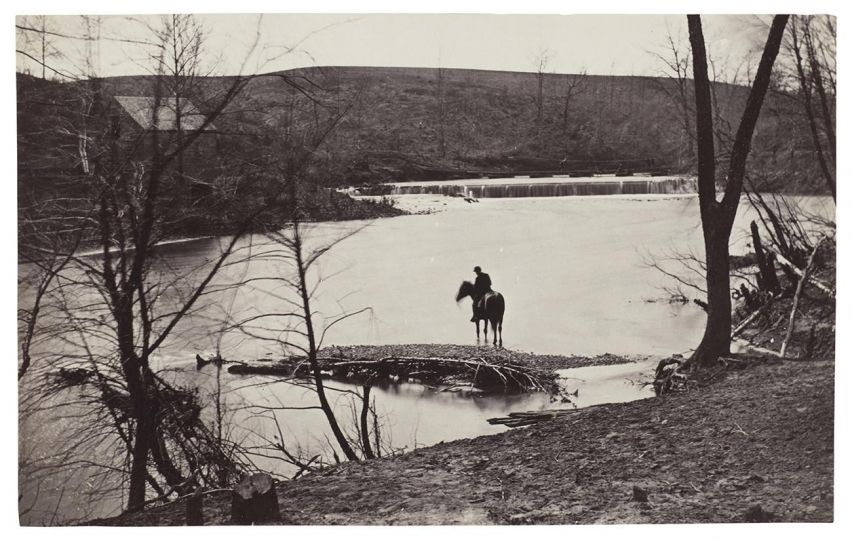

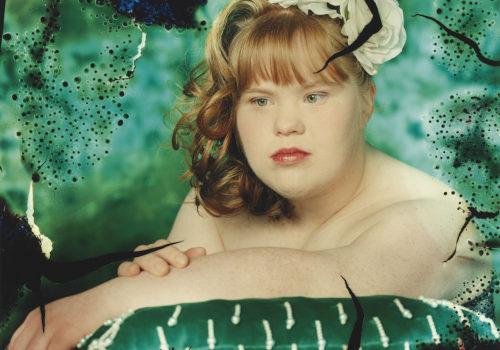

It was from that moment on that Penn combined his work at Vogue with personal research. Commercial work wasn’t enough. He would never abandon it and threw himself into it with the same quasi-mystical diligence. But he also wanted to express himself freely. For Vogue, he photographed the prettiest women in the world. For himself, on the other hand, he did nude studies of fat women that he would show only thirty years later. Accompanied by Lisa, an assistant, and a mobile studio, he traveled in the late 1960s from Dahomey, Nepal, and Cameroon, to New Guinea and Morocco. The result was a superb volume titled Worlds in a Small Room, published in 1974. In it, Penn finally got close to his Holy Grail: absolute control and mastery over light. “During my early years as a photographer, my studio was located in an office building, in an enclosed space with no windows, with only electric lamps to simulate the light of day. In that place, I would often catch myself daydreaming about being magically transported, along with an ideal north-facing studio, among endangered natives somewhere at the edge of the world. These remarkable strangers would come up to me, plant themselves before my camera, and in the northern light, I would document their physical existence.”

Irving Penn became increasingly devoted to his research. This marks the beginning of an astonishing exploration of his inner world. He who hated smoking, would photograph cigarette butts. He whose studio was as tidy as a Swiss clinic, would, for his personal projects, spill piles of garbage amassed in the streets. Only two brighter intervals came to break up this descent into the netherworld: in 1984, he did a book on flowers, and in 1988 a volume on Issey Miyake’s designer clothes. Of course, his commercial work was always there in the background. Doctor Irving and Mister Penn have always had the same passion for the still image. The critics, who had long shunned him, began to take note of Penn’s obsession with the passage of time, the anxiety about things that wear down, the apprehension of death. While the search for absolute perfection through anguish, torment, and obsession may be proper to artists, Irving Penn is one of the rare photographers to truly deserve this designation.

Jean-Jacques Naudet

A version of this article appeared in issue no. 2211 of the Paris Match magazine on October 10, 1991.

Irving Penn: Centennial

April 24 to July 30, 2017

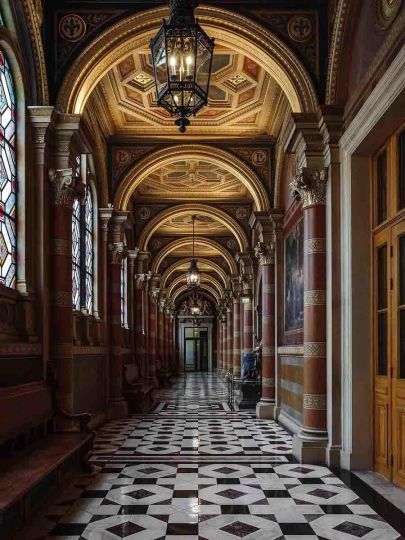

The Met, Gallery 199

1000 5th Ave

New York, NY 10028